- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Politics USA

About this book

Politics USA is a lively and authoritative introduction to American politics, giving students a rich and varied resource for all aspects of their course. The book provides expert and comprehensive analysis of US politics and government, including in-depth coverage of the presidency, the Congress, the Supreme Court and American foreign policy.

This third edition of Politics USA has been thoroughly updated to include analysis of

- Challenges and policies of the first Obama administration

- Recent results and developments in US elections

- Latest major decisions of the US Supreme Court

- Contemporary American Foreign Policy

This is an ideal introduction for students of US politics as well as anyone seeking to understand any or all aspects of politics in one of the world's most powerful and globally influential countries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Politics USA by Robert J. McKeever,Philip Davies,Robert McKeever in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction – A troubled nation

The first decade of the twentieth century was a traumatic one for the United States. The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 led to two major wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and a global ‘War on Terror’. These proved difficult and costly conflicts, which often appeared to lack clear focus and purpose. Even the killing of Osama bin Laden in May 2011 provided only a temporary lift to the war-weariness that seemed common among politicians, the military and citizens alike. When Secretary of Defense Robert Gates addressed the graduating class of cadets at the West Point military academy in February 2011, he told them ‘…you will be joining a force that has been decisively engaged for nearly a decade. And while it is resilient, it is also stressed and tired.’ A few months later, in a speech delivered in Brussels, Gates warned America’s European allies that the United States was tired of bearing what it considered to be a disproportionate share of the West’s military burden: ‘The blunt reality is that there will be dwindling appetite and patience in the US Congress, and in the American body politic writ large, to expend increasingly precious funds on behalf of nations that are apparently unwilling to devote the necessary resources …to be serious and capable partners in their own defense.’ While Gates’ speeches stopped well short of advocating a new era of American isolationism, they did indicate that the time was ripe for a fundamental review of when and how the United States should engage in military adventures abroad.

If a decade of war left the American people in a gloomy, introspective mood, the deep economic recession that began in December 2007 left them angry. The recession was the longest in duration since the Great Depression of the 1930s and began with the collapse of the housing market and the banking sector. Although the country officially came out of the recession in June 2009, the economy continued to be sluggish, with unemployment levels stuck around 9 per cent. Moreover, many of the new jobs created after the recession are lower-paying than those lost earlier. A further consequence of the recession was the record number of house repossessions that occurred as homeowners were unable to meet their mortgage payments. Add to this a bitter fight between Democrats and Republicans over the soaring budget deficit and it comes as no surprise that many Americans are pessimistic about the country’s economic prospects. According to a Gallup Poll taken in June 2011, 65 per cent of Americans believed that the economy was getting worse, while only 31 per cent thought it was getting better. Logically enough, when Gallup asked people in May 2011 what they considered were the most pressing problems facing the country, 74 per cent nominated economic concerns, while only 4 per cent mentioned foreign policy issues and 5 per cent health care and education problems.

This context provided the setting for both the congressional elections of 2010 and the early stages of the 2012 presidential election. The upsurge of hope that had propelled Barack Obama to victory in 2008 had long disappeared. In November 2008, Obama had captured 53 per cent of the popular vote in the presidential election. His approval ratings soared in the first few weeks in office, but soon began to decline steadily, roughly in line with the deteriorating economy. By the spring of 2011, those who disapproved of his performance as president outnumbered those who approved by 48 per cent to 43 per cent. The problem for the president was that his successes attracted strong condemnation from his opponents and often only lukewarm praise from his supporters. Despite his historic achievement in securing passage of his health care bill in March 2010, opinion polls showed that a clear majority of the public were opposed to it. While Democrats in particular were delighted with President Obama’s announcement in August 2010 that US combat missions in Iraq had ended, others were critical of his failure to keep his pledge to close the notorious Guantanamo Bay prison for suspected ‘enemy combatants’. Above all, however, it was the perceived failure of the president’s high-cost economic stimulus package to bring about recovery that underpinned the Republican triumph in the 2010 mid-term elections. The plan had involved $787 billion and was described by the president as ‘the most sweeping recovery package in our history’. While the plan prevented the recession from becoming a full-blown depression, Americans were disappointed with its results – and the president’s party felt the electorate’s wrath.

In the elections for the House of Representatives, the Republicans gained 63 seats from the Democrats and took control of the chamber. In the Senate, the Republicans made some important gains but the Democrats retained their majority, albeit a significantly reduced one. The voters had once again returned the country to ‘divided government’, a familiar phenomenon in modern American politics. With a Democrat in the White House, a solid Republican majority in the House of Representatives and a slim Democrat majority in the Senate, the scene was set for either a period of bipartisan cooperation or an increasingly bitter political stalemate. As is usually the case, it was the latter that occurred as the parties took up position in preparation for the 2012 presidential election.

The Tea Party movement

However, the dynamics of party politics have been rocked in recent years by the rise of the so-called ‘Tea Party’ movement. Taking its name from the Boston Tea Party of 1773, when Americans protested against colonial taxes by dumping tea from British ships into Boston harbour, it is essentially a populist movement vehemently opposed to high federal spending, high taxes and the federal government in general. Its ideology is libertarian in economics and its anti-Washington stance resonates strongly with American political culture. In sociomoral matters, however, it owes much to evangelical religious values.

Opinion is divided as to whether the Tea Party movement represents a new force in American politics or rather a re-energised but familiar conservative grouping. Noting the spontaneity with which the various elements of the Tea Party arose, some see it as a force exterior to and independent of the two-party system. There is some evidence to support this view. Although its ideology is perfectly compatible with conservative strands within the Republican Party, Tea Party-backed candidates have attacked and defeated well-established Republican politicians. In the 2010 federal election round, as many as eight ‘establishment’ Republican candidates were defeated in primary elections by candidates strongly identified with and funded by the Tea Party.

However, closer inspection suggests that the Tea Party movement is better understood as an insurgency within the broader Republican tent. It seeks to remove moderate Republicans and replace them with passionate, populist advocates of economic libertarianism and social and moral conservatism. Take, for example, the candidacy of Christine O’Donnell for the vacant Senate seat in Delaware in 2010. The Republican Party establishment in the state had backed Mike Castle, a moderate Republican considered capable of winning the seat in a traditionally Democrat state. O’Donnell, however, launched a vigorous and heavily publicized campaign appealing to Tea Party sentiments. When she won the primary, the media heralded the Tea Party as a powerful new force in American politics. Yet O’Donnell was a life-long Republican who had run for the Delaware Senate seat before. What was different this time was that she had latched onto the Tea Party movement for political and financial support and this took her to victory in the primary. More generally, a variety of studies have shown that there is a great deal of overlap between Tea Party activists and supporters and conservative Republicans. In elections, Tea Party supporters and conservative Republican candidates have sought each other out in an effort to move the Republican Party – and the Congress – to the right.

This new energy in conservative politics is not necessarily a boon to the Republican Party. The key to winning elections in the United States is attracting the votes of moderates in both parties and those who are often labelled ‘Independents’. The more extreme statements and positions of Tea Party candidates tend to alienate such voters, particularly when they have been subject to derision in the media. This was precisely the fate of O’Donnell in Delaware in 2010. Having won the Republican primary, she then lost by a margin of 57 per cent to 40 per cent to her Democrat opponent, Chris Coons. One analysis suggests that some 18 per cent of Republicans deserted their party and voted for Coons.

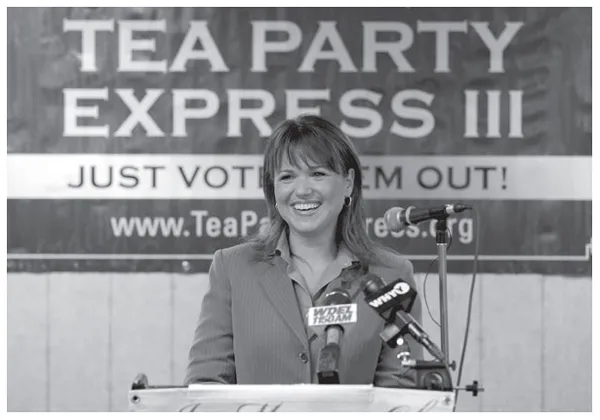

Figure 1.1 Christine O’Donnell, Tea Party candidate, during the 2010 Senate Republican primary campaign in Delaware.

Source: © AP/Rob Carr

Nevertheless, the conservative insurgency took another step forward when the Congressional Tea Party caucus was formed in 2010. Some 60 Republicans joined it, mostly members of the House of Representatives. Its leader, Michele Bachmann, a congresswoman from Minnesota, launched her bid in 2011 for the Republican presidential nomination. Other Republicans also saw the potential in using the Tea Party movement as a springboard to the White House. These included Sarah Palin, the Republican vice-presidential nominee in 2008 and Congressman Ron Paul of Texas, whose libertarian views are held to have inspired the Tea Party activists.

It may be that the Tea Party is not much more than re-branded conservative Republicanism, but that does not deny that it has touched a nerve with a significant section of the American people. What has made conservatives so angry? The short answer is: the Obama administration’s policies and Obama himself.

President Obama inherited the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. His response was broadly similar to that of President Franklin D. Roosevelt some 80 years earlier. Obama accepted that it was the federal government’s responsibility to lead the country out of recession, rather than simply waiting for business and industry to recover. He therefore embarked upon an ambitious stimulus package that injected some $787 billion into the economy in the form of government spending programmes and tax cuts. Inevitably, this sent the level of American debt soaring to unprecedented heights, although it should be emphasised that the national debt had been rising steadily since the early 1980s. Nevertheless, with the national debt now within touching distance of gross domestic product, alarm bells were ringing for many conservatives. There was a real concern that Obama was creating a dominant federal government that betrayed America’s political traditions.

This fear was fuelled by President Obama’s health care law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. Health care had been a bone of contention for many decades in the United States. With no national health system on the European model, Americans were responsible for securing their own private health insurance. For the economically comfortable this was no problem. Moreover, many employers offered private insurance to their workforce, so most Americans were covered. However, in 2008, some 46 million Americans were thought to have no health insurance because they could not afford it. Democrat presidents going back to Harry Truman (1945–53) had tried – but largely failed – to address this problem of health care for the poorest fifth of Americans.

In securing the passage of his health bill, President Obama achieved a cherished dream of many Democrats. However, a majority of the public oppose it, especially Republicans and Independents. First, critics charge that it is too expensive and that it will increase the budget deficit and the national debt. Second, they oppose the bill because it forces all Americans to take out health insurance, whether they wish to or not. ‘Obamacare’, as its opponents like to call it, therefore combines perhaps the three things that conservatives dislike most – federal expenditures, federal taxes and federal compulsion.

Some Americans see the Obama administration’s policies as ‘un-American’. Many of these go further and believe, literally, that Barack Obama is not an American. Barack Hussein Obama II, to give the President his full name, was born on 4 August 1961, in the state of Hawaii, to an American mother and a Kenyan father. His parents divorced in 1964 and his mother later married an Indonesian citizen. That was how the young Barack Obama came to spend four years in Indonesia from the age of six until he was ten, whereupon he returned to Hawaii.

This personal profile led a significant number of Americans to believe that Obama was not really born in Hawaii or anywhere else in the United States. This in turn meant that Obama was ineligible to be president, since the Constitution requires the holder of that office to be a ‘natural born citizen’. In 2008 the Obama campaign released the short form of his birth certificate. The so-called ‘Birther’ Movement, however, campaigned to force Obama to release the full or long-form version of his birth certificate. When he eventually yielded in April 2011, it was immediately condemned by Birthers as a forgery, although polls suggest that the release of the long-form certificate halved the number of Americans who are convinced he was not born in the United States, from 20 per cent to 10 per cent.

Another thread of conspiracy about Obama is that, although a professed Christian, he is secretly a Muslim. An opinion poll in 2010 revealed that while 34 per cent of respondents believed he was indeed a Christian, 18 per cent believed he was a Muslim and 43 per cent said they didn’t know. It seems that Obama’s middle name – Hussein – is the inspiration for the idea that Obama is a Muslim, though the four years he spent in Indonesia, a Muslim country, is also a factor.

For the most part, those who believe that Obama is not an American and is a Muslim are critical of his policies and align themselves with the Republican Party. In that sense, the conspiracies can be dismissed as the desperate tactics of those who have lost a political contest. On the other hand, the strangeness – not to say craziness – of the beliefs that underpin these conspiracy theories, together with the relatively large number of people who subscribe to them, tells us something about politics in the contemporary United States. It tells us that there is a bitterness and polarisation of politics in some sections of the population. It may also tell us that while most Americans are comfortable with an African-American as president, a minority are disturbed by what they see as an alien presence in the White House.

This bitterness and polarisation is also demonstrated in another feature of contemporary American politics: the decline in the standard of public discourse. Few would deny that the language used by some public figures has become much harsher over the last decade, as have the accusations they make against their opponents. Radio and TV ‘shock jocks’, such as Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh, attract large audiences with their blend of outrage and verbal aggression against all things liberal and Obama. Beck, who appeared on the conservative Fox News Channel, condemned President Obama in the following terms: ‘This President, I think, has exposed himself over and over again as a guy who has a deep-seated hatred for white people or the white culture …This guy is, I believe, a racist.’ Beck eventually went too far even for his employer when he began to promote nakedly anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and was taken off air. Rush Limbaugh has been the leading conservative shock jock since the late 1980s. He attacks, among others, liberals, feminists, environmentalists, gays and those who favour abortion rights. However, it is the attacks on President Obama that are perhaps the most shocking. There has been a tradition in the United States of showing respect for the president, even if one disagrees passionately with his policies. Limbaugh and others have ignored this tradition. On several occasions, Limbaugh has said that Obama was only elected president because he was black and traded on white guilt over the history of slavery. Gone, too, is any notion that the president is even patriotic. As Limbaugh put it: ‘Our nation was created in ways that allow human potential to prosper, and it created the greatest nation for people in the history of humanity. Now Obama is dismantling it, because he has no appreciation for our greatness. In fact, he resents it. He blames this country for whatever evils he sees around the world.’

It is one thing for media controversialists to engage in such discourses, but in recent years politicians have been following suit. Concerns over the deterioration in the standards of political discourse came under the spotlight following the shooting of Democrat Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords of Arizona, in January 2011. Giffords was seriously wounded when a gunman started shooting at a public meeting she had called at a supermarket in Tucson. While Giffords was the target, the gunman killed six people and wounded many more.

The veteran local sheriff expressed the view that the vitriolic language used by some public figures was responsible for creating a climate of bigotry and hatred in the country. And it emerged that Giffords had recently complained about being targeted by Tea Party favourite Sarah Palin on her website. Palin called for the recapture of 20 congressional districts whose Democrat members had supported President Obama’s health care bill. She identified them with the cross-hairs of a rifle sight. Palin had also commented: ‘Commonsense conservatives and lovers of America: Don’t Retreat, Instead – RELOAD.’ Palin’s use of such violent imagery was widely condemned and the offending item was quickly removed from the website. Palin issued a statement condemning the shooting and sending her condolences to Congresswoman Giffords and the other victims.

Figure 1.2 Sarah Palin website identifying 20 members of Congress who voted for President Obama’s health care bill. Their constituencies were marked by the cross-hairs of a rifle site.

Source: © Shutterstock/Covascf

Eventually, the man arrested for the shooting, Jared Loughner, was deemed mentally unfit to pl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface to the third edition

- Dedication

- Contributor

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1. Introduction – A troubled nation

- Part 1: The constitutional dimension of American politics

- Part 2: The socio-economic contexts

- Part 3: The representative process

- Part 4: The executive process

- Part 5: The legislative process

- Part 6: The judicial process

- Part 7: The policy process

- Index