- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Life Before Birth, Second Edition

About this book

This textbook presents essential and accessible information about human embryology including practical information on human health issues and recent advances in human reproductive technology. Starting with biological basics of cell anatomy and fertilization, the author moves through the development of specific organs and systems, before addressing social issues associated with embryology. Each chapter includes specific objectives, general background, study questions, and questions to inspire critical thinking. Human Life Before Birth also contains two appendices and a full glossary of terms covered in the text. Clinicians and researchers in this field will find this volume indispensable.

Key selling features:

- Explores all the developmental and embryological events that occur in human emryonic and fetal life

- Reviews basic cell biology, genetics, and reproduction focusing entirely on humans

- Summarizes the development of various anatomical systems

- Examines common birth defects and sexually transmitted diseases including emerging concerns such as Zika

- Documents assisted fertilization technologies and various cultural aspects of reproduction

Information

PART I

An overview of human development

Biology has no story to tell that is more fascinating than that of human development. A tiny fragment of matter, in the appropriate environmental context, is able to develop into a human baby. Birth, like the reality of stars in the heavens, is so common that we almost take it for granted. Yet for this event to occur, 266 days of cellular activity must pass with a precision that would impress the most critical of engineers.

To read and understand this text properly, the knowledge of basic terms, concepts, and anatomic landmarks is needed (Chapter 1). And to understand development, it is necessary to know something about cells, the interacting entities that result in development (Chapter 2) and genetics (Chapter 4). Two types of cell division (Chapter 3) are necessary for reproduction (Chapter 5) and development to occur. In addition to cell division, cells must also differentiate and become specialized members of the cellular society that is the human body. All of cell differentiation is fascinating, but none more so than gametogenesis (Chapter 6), the process by which seemingly ordinary cells give rise to the tiny motile sperm and the large expecting egg.

An enormous amount of human activity is concerned with fertilization—how to encourage it, how to prevent it, and humankind’s preoccupation with sexual behavior, originally designed to culminate in fertilization (Chapter 7). Fertilization launches human development.

In addition to continuing cell division and cell differentiation during embryogenesis (Chapter 8) and development of the fetus (Chapter 9), we see a third dramatic component of development, morphogenesis—the origin of form. Human development does not involve the growth of preformed parts but, rather, the gradual emergence of eyes and ears and arms and legs.

Development would not progress beyond the first week if it were not for the placenta, the most unique of human organs, and the umbilical cord (Chapter 10), through which the developing human communicates with the placenta. As the embryo and fetus grow, they need this life-support system. When studying the development of the baby, one must be mindful of the context in which this development occurs—the pregnant woman (Chapter 11). Then comes the day we celebrate annually for the rest of our lives, our “birth” day. We have no direct recollection of this event, but it is life-altering not only for us, but especially for our parents. Moreover, as dramatic as birth is, humankind, at least until the advent of fertility drugs, has been particularly enthralled by multiple births.

Chapter One

Before you begin

Chapter objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1.Correctly use and interpret the following anatomic landmarks and terms: anatomic position, superior, inferior, cephalic, caudal, rostral, medial, lateral, proximal, distal, dorsum, dorsal, venter, ventral.

2.Understand symmetry and explain the difference between radial symmetry and bilateral symmetry.

3.Distinguish between planes and sections, and explain how the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes divide the human body.

4.Explain the differences between the developmental timelines used by obstetricians and embryologists.

Before beginning our discussion of human development in the ensuing chapters, we need to learn some basic concepts that will guide the more detailed descriptions that follow later in the book. Our discussion will take place in this order.

•First, we will take up the “geographic” descriptions essential to any study of anatomy—adult or developmental.

•We will move to the fourth dimension—time—and briefly discuss the terminology used to discuss the progression of pregnancy.

•Finally, we will talk about comparative embryology. Although this book is primarily concerned with human development, many aspects of human development are particularly interesting when compared with that of other animals.

Anatomic descriptions

A large part of the content of human developmental biology is developmental anatomy. Anatomy is never static, but it is especially dynamic before birth. When you study the development of the human face during the second half of the embryonic period (the fourth through eighth weeks), you will be especially impressed by dynamic anatomy (morphogenesis).

To communicate about anatomy, it is necessary to have a common vocabulary shared by teacher and student; otherwise, the information transferred is not precise. This is especially true when the anatomy described is constantly changing. The terms explained here are frequently used in the descriptions in this text.

Anatomic landmarks

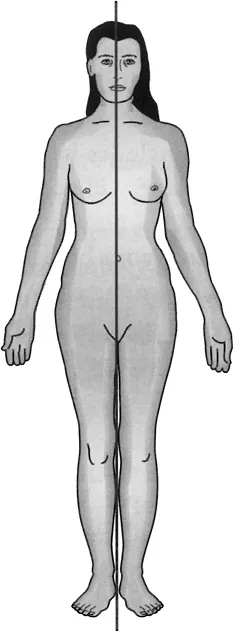

The anatomic position for a human is standing straight and upright, with arms at the sides and palms facing forward (Figure 1.1). The head is at the superior (top) end of the body, and other parts of the body are relatively inferior (below) to it. Because a dog walks on four legs, its head is anterior (front), and its tail is posterior (back). To avoid the confusion caused by four-legged and two-legged animals, we will use the term cephalic to refer to the head and the term caudal to refer to the tail of both. If we use these terms as adverbs rather than adjectives, they become cephalad (toward the head end) and caudad (toward the tail end). We may even refer to something on the head that is closer to the very end of the head than to some other reference point as rostral.

Figure 1.1Anatomic position and bilateral symmetry. The body is erect, the arms are at the sides of the b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Author

- Part I: An overview of human development

- Part II: Some details of human development

- Part III: Society and human development

- Answers to study questions

- Appendix A: Examples of birth defects by terminology

- Appendix B: Examples of birth defects by organ or system

- Glossary

- References

- Websites: In chapter order

- Index

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Life Before Birth, Second Edition by Frank Dye in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Gynecology, Obstetrics & Midwifery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.