- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Truman Years, 1945-1953

About this book

The Truman Years is a concise yet thorough examination of the critical postwar years in the United States. Byrnes argues that the major trends and themes of the American history have their origins during the presidency of Harry S. Truman. He synthesizes the recent Truman literature, and explains the links between domestic U.S. political and social trends and cold war foreign policy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Truman Years, 1945-1953 by Mark S. Byrnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

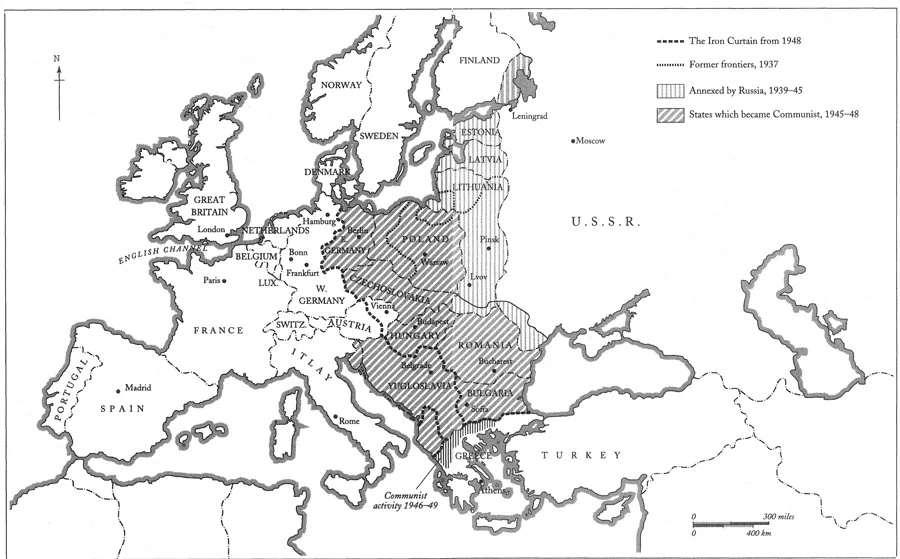

Map 1 Cold war Europe, 1946

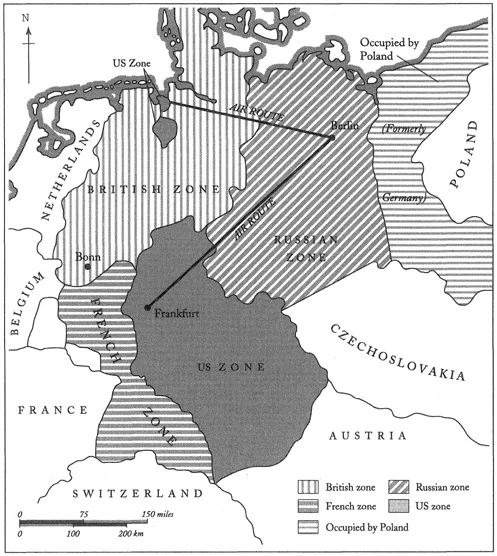

Map 2 Cold war Germany, 1946

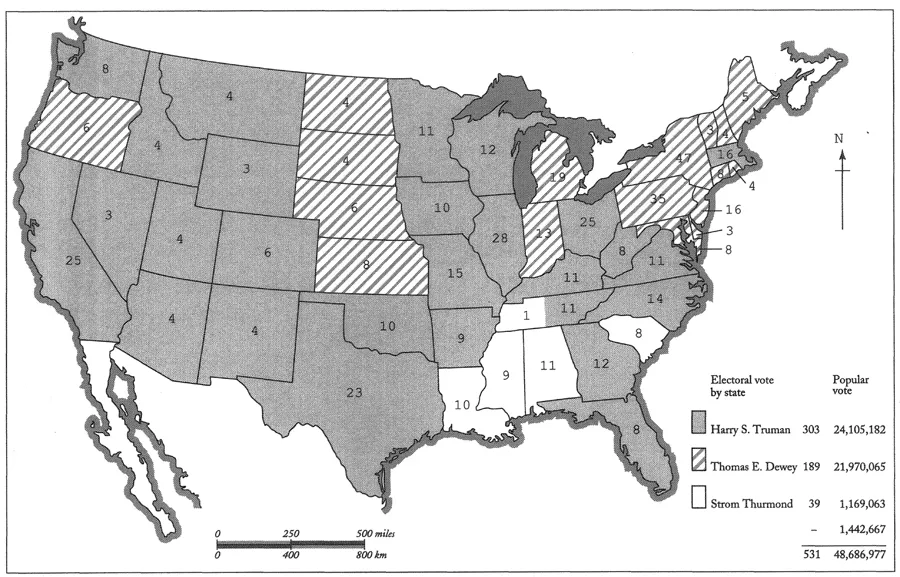

Map 3 The 1948 election results

| CHAPTER ONE |

INTRODUCTION: THE UNITED STATES IN 1945

It is rare when a single year emerges as a clear line between historical eras. It is even more rare when that year coincides with a particular presidential administration. Yet such is the case with 1945. Perhaps only 1865, with the nearly simultaneous death of Abraham Lincoln and the end of the Civil War, rivals 1945 as a clearly defined turning point in American history. The death of Franklin Roosevelt came only weeks before the end of the war in Europe, and months prior to the surrender of Japan. The burden of the tremendous shift from fighting the most destructive war in history to rebuilding the devastated battlegrounds of Europe and Asia fell on a relatively untested politician from Missouri, Harry S. Truman.

Franklin Roosevelt bequeathed to Harry Truman a nation far different from the one he inherited from Herbert Hoover in 1933. In that dark year, the United States was wallowing in the depths of the Great Depression. As war approached in Europe and Asia, the country turned inward, reverting to the reflexive isolationism which had dominated so much of its history. On the April day in 1945 when Harry Truman first took the oath of office, the United States was the dominant economic power in the world, and stood on the brink of military victories in both Europe and Asia, the leader of an international coalition against the fascist powers.

The transformation was nothing short of remarkable. The entire federal budget in 1939 was approximately $9 billion. In 1945, it was over $100 billion. The gross national product more than doubled during the war. With breathtaking speed, the United States had undergone a dramatic evolution, but the future remained obscure. Would the price of peace be the disappearance of the prosperity of the war years? Would the American public, its adversaries abroad vanquished, return to its traditional aversion to involvement in European affairs? Over the next nearly eight years, Truman would preside over the creation of both the postwar world and postwar America. The Truman administration was a formative time, when the tremendous forces unleashed during World War II would take on concrete expression, an era in which patterns were established in both domestic and world politics which would mark the United States for the rest of the century.

Their confidence first shaken by the deprivation and want of the 1930s, and then restored by triumph in war, Americans were simultaneously secure and fearful in 1945. They had greater power, greater wealth than ever before. They also had more to lose than ever before, and a haunting sense of how easily it might all vanish. The stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent downward spiral of the economy had shown that great prosperity could be fleeting. The shocking Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor removed the illusion that the United States was invulnerable behind the mighty natural defenses of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Even the awesome power that helped end the war was cause for deep concern: how safe was anyone in a world in which a city could disappear in a flash?

The most obvious and immediate burden facing Truman was of course the end of World War II It was nonetheless one of the least of the challenges the former farmer and failed haberdasher faced in his presidency. The war was nearly over in Europe; Germany’s collapse was expected soon. While the future looked more ominous in the Asian theater, within three months, Truman would receive the news of the successful testing of the atomic bomb; a month later, the Japanese would surrender.

Far more daunting and intractable were the problems of peace. In foreign affairs, the final defeat of the Axis produced no Utopian paradise. The destruction and consequent misery produced by the war would take years to overcome. The wartime alliance with the Soviet Union slowly disintegrated, producing a new sense of danger in the world, a new dragon to slay. In the aftermath of the war effort, many Americans seemed to yearn to return to a simpler time and their traditional isolation from political involvement in world affairs.

Even the more pleasant prospect of a prosperous life at home was not without qualification. Yes, the massive government spending of the war had finally ended the Great Depression. But the new-found wealth of the nation seemed precarious to many Americans, Would the prosperity which came during the war survive during the peace? What was the best way to ensure that it did: continuing New Deal/wartime-style management of the economy, or a return to a more laissez-faire approach now that the economic and military crisis had passed? How did one convert an economy geared to war production back to civilian purposes without massive disruption? Where would the millions of servicemen find work once they returned home from the war?

Perhaps even more profound than these immediate economic concerns were the ramifications of the social changes the previous years of depression and war had wrought on American society. The humiliation many men felt at the inability to perform their traditional role as provider in the Depression had taken a toll on patriarchy. The imperatives of war production had pressed millions of women into new, previously unthinkable, lines of work and had begun to erode the entrenched view of the proper place of women. Ä similar dynamic was transforming race relations. Millions of African- American men and women, who served their country in uniform or in the factories, would find it increasingly difficult to accept the second-class citizenship of the Jim Crow segregation* of the South and the de facto discrimination of the North. The disruptions of the Depression and the war undermined the family as a unit of social stability, foreshadowing the youth rebellion of the 1960s.

It fell to Harry Truman to lead and manage these profound political, economic and social changes. Truman made no bones about his sense that he was not up to the task. He confessed to his diary that he felt “shocked when I was told of the President’s death and the weight of the Government had fallen on my shoulders’ [Doc. 1], In many ways, however, Harry Truman was no accidental president. The fact that the former senator from Missouri was in line to become president was not the product of presidential or party whim. It was a calculated decision, one which reflected the changing mood and needs of the nation. Truman was a New Dealer who was uncomfortable with some of the ‘professional liberals’ who were drawn to Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). He was a parochial man from the Midwest who had never left the United States prior to his service in World War I, yet drew from that experience and his reading in history an appreciation for the more cosmopolitan world-view of the eastern establishment.

Even temperamentally, Truman was well-suited to his time. Lacking both the dour stoicism of Herbert Hoover and the ebullient optimism of Franklin Roosevelt, Truman reflected the ambivalence of his age. As many contemporary commentators and subsequent biographers have noted, Truman’s scrappy, decisive image sometimes concealed a deep-seated insecurity and sense of inferiority. Like the nation he led, Truman could be both cocky and paranoid, generous and petty, visionary and parochial He was a man raised on nineteenth-century values thrust suddenly into the leadership of a rapidly changing twentieth-century nation. If he often fumbled and stumbled in his effort to reconcile this new world with the quite different one which produced him, many Americans no doubt saw in that struggle a reflection of their own bewilderment at how quickly their world had changed around them.

In that ad hoc improvising which marked much of Truman’s presidency, however, the contours of postwar America were established: a status quo politics that both accepted the basic outlines of the limited welfare state which was the legacy of FDR’s New Deal, and resisted its expansion; an internationalist world-view which assumed the necessity of American leadership, defined increasingly by the cold war straggle with the Soviet Union; an evolving transformation of race and gender roles in American society. Overall, the Truman years were a time of transition and transformation, as the United States adjusted to events at home and abroad which dramatically changed the nature of American government, society and diplomacy.

| PART ONE | YEARS OF UNCERTAINTY. 1945–46 |

| CHAPTER TWO |

THE DECISION TO DROP THE ATOMIC BOMB

One of the momentous events that marks the year 1945 as a turning point, not only in American but in world history, is the advent of the atomic weapons. In August, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, the first (and thus far only) use of nuclear devices in combat. For the first time in history, the human race faced the prospect of complete annihilation. Nothing would ever be quite the same again.

Harry Truman always maintained that once he made the decision to use the atomic bomb, he never gave it a second thought. If that is true (and there is some reason to doubt that it is), the president was the only one who considered the subject closed. The controversy over Truman’s decision has continued ever since. It was perhaps the most significant decision that Truman ever made, with far-reaching consequences, and it is still hotly debated more than 50 years later [18; 63; 91].

ENDING THE WAR IN ASIA

Bringing World War II to a quick, successful conclusion was the most pressing matter the new president faced. In Europe, it was only a matter of time. Allied forces were closing on Berlin from east and west, and Germany would surrender less than a month into Truman’s presidency. The Asian theater was another matter entirely. The tortuous process of approaching Japan through the island-hopping campaign was slow and brutal. Truman’s first weeks as president coincided with the battle for Okinawa, which lasted until June. The battle saw 16 US ships sunk (and another 185 damaged) by Japanese kamikaze suicide attacks. Apart from the actual damage done, the kamikaze attacks created the impression of a fanatical resistance by the Japanese which could only be overcome at great cost. At the time of the German surrender, V-E Day, 8 May 1945, American political and military leaders feared that the war with Japan might go on another 12–18 months. Preliminary plans called for a potential invasion of the Japanese home islands in 1946 [16; 142].

On the diplomatic front, the United States had long been pushing the Soviet Union to enter the war against Japan, which they agreed to do at the Yalta Conference* in February 1945. According to the agreement, the Soviets were to enter the Asian war three months from the end of the war in Europe, The United States hoped that the general desperation of the Japanese position, combined with the Soviet entry, would bring an end to the war without the necessity of an invasion of the Japanese home islands, which everyone assumed would exact a high cost in lives lost – tens of thousands at least. After meeting with Stalin at the Potsdam Conference* on 17 July, Truman noted in his diary that the Soviets would be in the war by 15 August. Fini Japs when that comes about,’ Truman wrote [5 p. 53].

The successful testing of an atomic device at Alamogordo, New Mexico on 16 July 1945, raised another possibility: atomic strikes on Japanese cities which would force an early surrender. Despite the later controversy over the decision, there seems to have been little hesitancy on Truman’s part, and little vocal dissent among the upper reaches of policy-making. The Interim Committee, appointed by Truman to make recommendations regarding the use of the weapon, had recommended in May 1945 that the bomb be used without warning against a “vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.’ The purpose, they concluded, was to ”make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants as possible.’ A group of atomic scientists who worked on the project advised against ‘an early unannounced attack against Japan/ The chances of controlling a potential arms race would be increased, they argued, by a demonstration in an uninhabited area. The government’s scientific advisory committee rejected that idea, concluding that ‘we see no acceptable alternative t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- An Introduction to the Series

- Note on Referencing System

- Author's Acknowledgements

- Publisher's Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Map 1: Cold war Europe, 1946

- Map 2: Cold war Germany, 1946

- Map 3: The 1948 election results

- 1. Introduction: The United States in 1945

- Part One: Years of Uncertainty. 1945–46

- Part Two: Retrenchment and Vindication, 1947–1948

- Part Three: Growing Opposition, 1949–50

- Part Four: Under-Siege, 1950–53

- Part Five: Documents

- Chronology

- Glossary

- Who's Who

- Bibliography

- Index

- Seminar Studies in History