![]()

Marilynn B. Brewer

University of California,

Los Angeles

Broadly speaking, social cognition is the study of the interaction between internal knowledge structures—our mental representations of social objects and events—and new information about a specific person or social occasion. As a subfield of social psychology, social cognition draws liberally from theory and methods of cognitive psychology, but considerable attention is given to differences between social cognition and nonsocial cognition. Most often the distinction is made in terms of the nature of the object of perception. Ordinary cognition becomes social when the target of interest is a “social object,” usually another person or group of persons.

Social objects are distinguished from other objects along a number of dimensions. In particular, persons are likely to be dynamic rather than static, active rather than passive, and to be perceived as causal agents—sources, rather than objects (Ostrom, 1984). In comparison to object categories, social categories have been postulated to be overlapping rather than hierarchically organized (Holyoak & Gordon, 1984; Lingle, Altom, & Medin, 1984), disjunctively rather than conjunctively defined (Wyer & Podeschi, 1978), and more susceptible to accessibility effects (Lingle et al., 1984).

The differences between social and nonsocial cognition may derive as much from differences in research focus and method as from any intrinsic differences in psychological processes. The study of object perception is generally concerned with the structure, format, and utilization of object categories or concepts. Once an adequate set of object categories has been acquired by the perceiver, individual objects are rarely encoded except as instances of some class. Such “top-down” processing assures stability of perception against recoding the same or equivalent objects across different occasions (Grossberg, 1976).

In contrast to the above, the study of person perception can best be characterized as the study of concept formation rather than concept utilization. Impression formation processes are assumed to be bottom-up, or data-driven, with an integrated representation of the individual person as the final product. The present paper challenges this prevailing view of the person perception process by proposing an alternative model of social cognition that incorporates top down processing as well as data-driven constructions. In the sections that follow, the differences between these two modes of impression formation are elaborated, and the implications for how and when social cognition differs from object perception are discussed.

TWO MODES OF PERSON PERCEPTION

Though they differ in their conceptualization of the integration processes involved, the classic impression formation theories of Asch (1946) and Anderson (1965) both conceive of the person perception process as the formation of an integrated impression derived from the stimulus information provided. Asch (1946), for instance, was convinced that the ability to form impressions of individual persons is a critical human skill:

This remarkable capacity we possess to understand something of the character of another person, to form a conception of him as a human being … with particular characteristics forming a distinct individuality, is a precondition of social life. (p. 258, italics added)

These earlier theories of impression formation pretty much ignored information overload and cognitive capacity limitations in their conceptualizations of the person perception process. It was assumed (implicitly, at least) that when a perceiver is presented with information about a previously unfamiliar person, a kind of “mental slot” is created to receive and process data about that person. As individual pieces of information are encountered, they are integrated, on-line, with previously received information to form (or modify) a unified impression of the person as a single unit.

More recent social cognition models (e.g., Asch & Zukier, 1984; Burnstein & Schul, 1982; Hamilton, 1981; Hartwick, 1979; Srull, Lichtenstein, & Rothbart, 1985) place greater emphasis on the interaction between incoming stimulus information and prior knowledge (schemas), but still postulate a single process of selection, abstraction, interpretation, and integration (Alba & Hasher, 1983) that culminates in a person-based representation of the information provided. Once an integrated representation has been formed, further information processing and judgments about the target individual may be guided by the integrated impression as much or more than the original trait or behavior information on which it was based (Carlston, 1980; Lingle, 1983; Lingle & Ostrom, 1979; Schul, 1983). However, stimulus-based, on-line concept formation is clearly assumed to be prior to these memory-based impression effects (Hastie & Park, 1986).

Recent research casts doubt on the assumption that individual persons—more than any other object—automatically serve as the basis for organizing information in a complex stimulus array (cf. Pryor & Ostrom, 1981). Instead, social information processing may be organized around available social categories, which include mental representations of social attributes and classes of social events, social roles, and social groups. One reason that earlier research on impression formation failed to recognize this is that the typical research paradigm presented information to subjects about one person at a time, with all information pertinent to a particular stimulus person provided in a single block (either successively or simultaneously). Hence, impressions that were person-based could not be distinguished from category-based organization of the same information.

Based on a series of studies utilizing stimulus situations in which a variety of social information is presented about each of several persons, Pryor and Ostrom (1981; Ostrom Pryor, & Simpson, 1981) have suggested that person-based encoding is the exception rather than the rule in such complex information settings. Person-based organization in recall of information is found only for previously familiar persons (Pryor & Ostrom, 1981), when there is a substantial overlap between person information and prior social categories (Pryor, Kott, & Bovee, 1984), or when future interaction with individual stimulus persons is anticipated (Srull & Brand, 1983). Even the addition of pictorial information was not found to enhance person-based clustering in memory, although such visual cues did improve overall recall for social information (Lynn, Shavitt, & Ostrom, 1985).

Pryor and Ostrom’s conclusions are supported by other research on the effects of memory load on person memory and on the differences between memory for persons as individuals versus persons in groups. Rothbart, Fulero, Jensen, Howard, and Birrell (1978) demonstrated that under low memory load conditions (i.e., few instances of person-trait pairings), subjects organized their impressions of a group around the characteristics of its individual members. When the amount of person-trait information increased, however, subjects organized trait information in an undifferentiated way around the group as a whole, failing to distinguish between repeated occurrences of a particular trait in the same individual and comparable repeated occurrences of that trait in different individuals.

If individuals are observed in a group context, the ability of a perceiver to remember which individuals were associated with specific traits or behaviors is apparently dependent on categorization processes. Category identity (such as race or gender) can either facilitate or interfere with accuracy of person recognition, depending on the nature of the group composition. When the categorical identity of an individual in a group is distinctive, person-based memory is enhanced (McCann, Ostrom, Tyner, & Mitchell, 1985; Taylor, Fiske, Etcoff, & Ruderman, 1978). When groups or subgroups of individuals are homogeneous with respect to such category identity, however, recognition errors are enhanced and person-based organization in recall is decreased (Arcuri, 1982; Brewer, Dull, & Lui, 1981; Frable & Bern, 1985; Taylor et al., 1978).

Further research along these lines suggests that the way new information is integrated with previous impressions differs for perceptions of individual persons and persons in groups or aggregates. With impressions of single individuals, information that is inconsistent with previously established expectancies is processed more elaborately, and recalled better, than new information that is consistent or irrelevant to prior impressions (Hastie, 1980; Srull, 1981; Srull et al., 1985). When the same information is dispersed among members of a social category, however, items that are inconsistent with category stereotypes are remembered less than congruent items (Carney, DeWitt, & Davis, 1986; Stern, Marrs, Millar, & Cole, 1984; Wyer, Bodenhausen, & Srull, 1984).

Because high information load and input from multiple stimulus persons are certainly characteristic of many real-life social settings, research on impression formation in groups casts doubt on the ecological validity of person-centered views of social perception. In contrast to perspectives that emphasize the unique aspects of social cognition, I propose an alternative position based on the following two contentions: (1) The majority of the time, perception of social objects does not differ from nonsocial perception in either structure or process. (2) When it does differ, it is determined by the perceiver’s purposes and processing goals, not by the characteristics of the target of perception. The same social information can be processed in a top-down manner that results in category-based cognitions, or in a bottom-up fashion that results in person-based representations, with implications for how new information is received, incorporated into existing knowledge structures, and used in making social judgments.

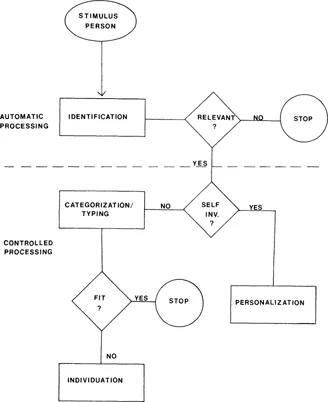

Both these premises are incorporated in the processing model represented in Fig. 1.1. This representation should not be considered a comprehensive processing model of the level of generality proposed, for instance, by Wyer and Srull (1986). Rather, it should be viewed as representing that portion of social information processing in which incoming information about a new stimulus person (or set of persons) is integrated with prior knowledge drawn from long-term memory. The model postulates two different routes by which such integration can take place. Which route is taken ultimately affects the form in which the new information is transferred to permanent storage.

The rectangles in the figure represent processing stages, each involving different types of knowledge structures and rules of inference. The processing modes are stages in the sense that they are assumed to occur sequentially; stages later in the sequence will not be activated until prior processing stages have been completed. Consistent with the “cognitive miser” perspective on social cognition (Fiske & Taylor, 1984), it is assumed that the individual perceiver resists moving to processing stages that require elaboration or modification of existing cognitive structures, unless it is required by certain decision rules. These decision rules (represented by diamonds in Fig. 1.1) reflect the demands of the stimulus configuration and the perceiver’s goals or motives. If a satisfactory resolution of the stimulus information is achieved at an early stage, no further processing will be undertaken (as represented by the “stop” symbols in Fig. 1.1).

FIG. 1.1. Dual processing model of person cognition.

The process begins with the recognition that the stimulus environment contains a person or group of persons. Information about the stimulus person may be apprehended directly, or indirectly through verbal description. In either case, the model assumes that the mere presentation of a stimulus person activates certain classification processes (the identification stage in Fig. 1.1) that occur automatically and without conscious intent. This stage is common to all person perception. It is only in later stages, which are subject to conscious control, that significant differences in modes of processing take place.

The primary distinction drawn in the model is that between processing stages that are category-based (those depicted in the left-most pathway in Fig. 1.1) and processing that is person-based (personalized). The two types of processing result in different representations of the same social information. Category-based representations are assumed to result from processing that is primarily top-down, while personalized representations result from bottom-up processing.

This distinction parallels that made by Fiske and Pavelchak (1986) between category-based and “piecemeal-based” affect. The present model differs in its emphasis on cognitive representations rather than evaluative judgments of social objects, and in its incorporation of a levels of processing approach. Fiske and Pavelchak focus on stimulus properties as the primary determinant of the type of processing that will be activated. Trait information that fits an available category label is assumed to elicit category-based affect, while traits that are not congruent wi...