eBook - ePub

Human Resources Management in Construction

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Resources Management in Construction

About this book

Human Resources Management in Construction fills an important gap in current management literature by applying general principles of human resources management specifically to the construction industry. It discusses and explores findings from research to supplement the theoretical and practical procedures used. It explores issues such as the technology used and the pattern of social and political relationships within which people are managed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The diversity of schools of management and the social sciences share a common base of concern for people and their behavior – both individually and collectively. Due to the dynamics of societies, not only are birth, death and taxes certainties but, perhaps, the most important certainty is ‘change’. Change generates uncertainty and risk about the future; often, data are sparse and so decisions are frequently highly judgmental. Managers are concerned about the future as the future can be influenced, if not changed radically; the past and the present are fixed. So, managers make decisions, necessitated by and effecting changes, which necessarily concern people.

Construction is a labour-intensive industry. The degree of labour intensity varies from sector to sector, project to project, country to country but usually within quite narrow boundaries. The concept of labour intensity is relative between industries. Common measures are value of output per person; value of output per operative; value of plant and equipment per operative; output as percentage of GDP relative to percentage working population in the industry. Such measures are not without statistical difficulties – definitions of the boundaries of the industry; obtaining data from the many very small firms. Many consultants consider themselves (and are regarded and ‘counted’) as associated with but not part of construction. Clients, increasingly, employ construction personnel in-house; many large private sector and numerous public sector organizations have a construction division or department; many individuals undertake DIY activities and most countries’ construction industries have a ‘black economy’ at work.

Hence, people are the foci of alternative views of the industry. Construction exists to contribute to the satisfaction of human needs and wants; it is organized by people; it employs people. Only relatively recently has the pervading importance of people begun to be recognized in essence and extent. It is the personal interactions which generate demands and determine the nature of supply responses.

Whether humans can, or should, ever be regarded as resources is complex and questionable. This book considers a wide variety of construction-based issues of human interactions and examines how such interactions can be managed.

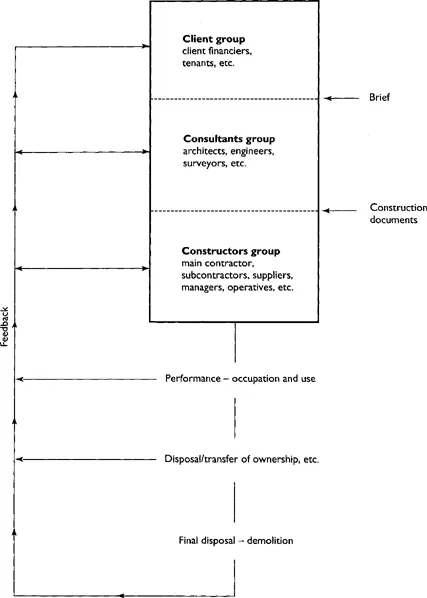

Human groups

It is all too easy to regard an organization, or, indeed, any group of people, as having its own identity, distinct from but incorporating the identities, goals and values of the individuals of which it is comprised. Whilst many groups do have a corporate identity, corporate activities remain subject to influences from individuals and sub-groups. An overview of construction, as in Figure 1.1, provides classification of human groups as Clients (public/private; large/small; individuals/corporate), Consultants (architects; engineers; surveyors) and Constructors (building/civil engineering; main contractors; subcontractors; management contractors/design and build contractors; operatives/managers, etc.). Clearly, other groups are involved less directly – financiers, insurers, planning authorities, tenants – although the influences of such groups are being recognized increasingly.

Clients

For all but very small projects, the client is unlikely to be an individual. As Cherns and Bryant (1984) noted, corporate clients are complex organizations which include many sub-groups. Once a project reaches the industry (i.e. emerges from the client as a design brief), it has undergone much scrutiny and debate. It is likely that the project represents a ‘victory’ for the sponsoring group within the client organization and, hence, a defeat for other groups who, due to capital rationing, may have seen their projects put into abeyance or abandoned.

Within the client organization there are vested interests some of which will seek to accentuate the success of the project and others the converse (to the advantage of their project proposals in the future).

Broadly, clients are either experienced and/or expert (sophisticated) or naïve. Expert clients build often and, commonly, employ construction professionals in-house, know what performance can be demanded and how to obtain the required performance; such clients ‘drive’ projects. However, the majority of clients are naïve, they build very infrequently, know little of the industry (except via image) and may be influenced easily – by advertising or/and advice of the first contact with construction personnel (usually an architect). Hence, for naïve clients, those who obtain first contact with them regarding a project are in a significantly advantageous position.

Consultants

Normally, the consultants’ group comprises those concerned with design, primarily architects, structural/civil engineers, services engineers, quantity surveyors – but the group will expand to incorporate project managers, planners (town and programming) and various other specialist service providers. Most projects require inputs of various design specialisms whether they be provided through consultancies or by a design and build contractor.

In project chronology, the design phase shows the first major manifestation of functional fragmentation typifying the construction industry. The interface problems between separate design organizations are subject to the over-riding factor of the major interface with the client – usually the responsibility of the ‘lead consultant’ (architect in building; civil engineer in civil engineering). In a study of architectural practice, Mackinder and Marvin (1982) found that most clients (the majority being naïve) do not know what information should be provided to constitute a (good) brief but, much more alarming, most architects do not know what briefing information is necessary.

Fig 1.1 Overview of the provision of construction and main groupings of human resources

General tendencies

Initial decisions tend to have the widest ranging effects: Kelly (1982) noted that about 80 per cent of the cost of a building was committed by around 20 per cent of elapsed design time. Hence, attention to early decision making is of great importance. Perhaps too commonly, with little external guidance and often in a matter of a few hours, the architect determines the arrangement of spaces and other preliminary design aspects using, primarily, aesthetic criteria.

In seeking to overcome design problems, Mackinder and Marvin (1982) found that architects seek solutions in the following sequence:

• own experience

• immediate colleagues’ experience

• product leaflets

• practice library

• research findings and own research

Clearly, the heavy reliance placed on experience does raise the question of what constitutes experience – at least, what is remembered. Recall may be quite selective, especially in the context of incidental (experiential) learning, as is likely to occur in work situations. Condemnation, perhaps due to the vehemence of its administration and associated guilt feelings, is likely to be remembered much more strongly and clearly than praise; further, many managers condemn much more readily and frequently than they praise. Hence, designing from experience is likely to have a very much stronger input of avoiding repetition of failures than of repeating successes – a conservative approach, tending to perpetuate the ‘safe’ status quo.

General consequences

There has been a tendency amongst consultants to carry out functions sequentially; the required inputs from various consultants occur discretely and so, coupled with obtaining such objectives as planning permission, etc, the design phase becomes protracted. Project finalization activities (agreeing final account, etc., which involves the quantity surveyor primarily) may be ‘stockpiled’. Hence, in various ways, consultants are both able to cope with unexpected urgent tasks and to have work to fall back on during slack periods. Such approaches facilitate constant employment of resources in the consultant firms themselves but the design phase is elongated notably over what could be achieved by more parallel working, as in NEDO (1983). A significant proportion of contractors’ funds are therefore tied up for unnecessarily (and hence costly) long periods – a notable proportion of such funds is written off each by contractors.

It is apparent that the desire for full and continuous employment of their resources amongst consultants (an imperative under fee bidding and during recession) has consequences detrimental to clients and to constructors: to clients through protracted design periods and conservative design tendencies; to constructors through extended periods of financial ‘lock-up’. Unsurprisingly, there are benefits too: longer design periods afford greater opportunity for iterative design development and evolution (testing alternatives, etc.), fully employed resources yield a version of high productivity which should reduce prices (fee bids) and delays to (final) financial settlements on projects and aid clients’ cash flows on individual projects, although, to remain viable businesses, contractors are likely to seek recovery of such shortfalls on future jobs!

General constraints

Frequently, consultants (particularly architects) seek to be and regard themselves as being aloof and separate from the construction industry. Seeing themselves as consultant (artistic) designers, they are cast in the role of guardians of cultural creative input to the built environment, charged to tell clients what they really want (what is good for them and the community) and determining what constructors build. Cultural custodians to the exclusion of carbuncles!

Increasing involvement of architects (and other design consultants) in the expanding sphere of design and construct serves to temper extreme eccentricities and to foster appreciation of others’ requirements and the consequent enhancement of designs achieved through that approach.

Constructors

The organization of construction has been transformed over recent years: fragmentation of activities has become markedly more pronounced to the extent that the main (general) contractor provides the primary construction management for execution of construction work by subcontractors, even for primary trades such as bricklaying and carpentry.

Current tendencies

Since the late 1970s, employment in construction operations has become more casual and fragmented, reversing the trend of decasualization of employment (which had persisted since the ‘navigator’ era of the 19th century); a trend which has been embodied in employment legislation, such as the Employment Act, 1980. A casualty of the return to fragmented, more casual employment has been operative training; de-skilling remains a highly contentious issue despite the greatly reduced requirements for many traditional skills (e.g. thatching) and the needs for new/different skills (e.g. dry lining).

Consequent upon the structural/process changes which have occurred amongst constructors, is a shift in the industrial power-base. Due to their metamorphosis into management contractors, the general contractors have, to a significant degree, relinquished their control of project price determination (if it ever was within their real control); such power now rests in major subcontractors and suppliers. In the long period, in a capitalist economy, all businesses must earn normal profit as the minimum return on investment for survival. However, in the short period – such as forms consideration of an individual construction project – much more pricing freedom exists in order to bid keenly, to buy work, to ‘take cover’, etc. Thus, for an individual project, the main contractor retains the position of arbiter of the price to be bid (and the primary consequence-bearer thereof).

General tendencies

The traditional model of price determination shows price to the predicted cost plus mark-up, i.e. estimate plus adjustments plus ‘allowances’ plus profit. However, particularly in extreme environments (recessions or booms), market conditions are the primary determinants, within limits, of the prices for individual projects. Greater variability still pertains to final prices of projects which, to a significant extent, are determined by the negotiating skills of the people involved and the rel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- The authors and acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Human resources management in the context of construction

- Chapter 3 External issues affecting human resources management in construction

- Chapter 4 Organizational behaviour

- Chapter 5 Industrial relations in construction

- Chapter 6 Interviewing for staff selection

- Chapter 7 Management development

- Chapter 8 People and information

- Chapter 9 Women in construction

- Chapter 10 Directions in human resources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Resources Management in Construction by David Langford,R.F. Fellows,M. R. Hancock,A.W. Gale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.