- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Many primary school teachers feel that they do not have sufficient knowledge or understanding of scientific subjects, simply because they are not science specialists.

Written in clear jargon free style, this book takes a step-by-step approach to all the topics of the National Curriculum for science at Key Stages 1 and 2. Throughout, it gives useful illustrations and real life examples to demonstrate the ideas being raised.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Life processes

NIGEL SKINNER

Introduction

What is life?

The processes of life

Summary

1

LIFE PROCESSES

INTRODUCTION

Living things share certain characteristics or ‘life processes’ which distinguish them from non-living things. To remain alive they must live in places that provide them with the things they need to keep their life processes going. Individual organisms will die, but life will go on (we hope!) because some will reproduce before they die. In this chapter the life processes common to animals and plants are discussed.

WHAT IS LIFE?

If children are asked the question ‘How do you know that you are alive?’ their responses will often include ideas about being able to walk and run, to make noises and talk, to think, to breathe, to see and hear, to think, and having a heart which beats. Some of these things are also exhibited by other living things but many are not. Clearly, plants do not walk or run and probably don’t think much! Successful teaching about what it means to be alive needs to move pupils away from their ‘human’-centred views towards a more general understanding of the concept of ‘living’.

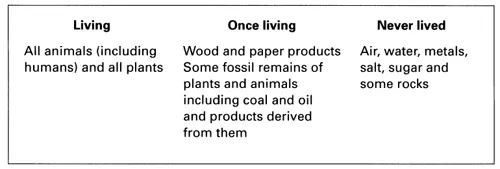

The things that we find around us can all be placed into one of three groups:

- those that are living;

- those that were living and are now dead;

- those that have never been living.

Familiar things belonging to each group are listed in the box:

It is not always easy to decide which group something is in. Difficulties arise because the characteristics which we use to recognise that something is alive are not always easy to detect (and are not displayed at all when something has died). Children sometimes think that if something moves or makes noises then it must be alive. Cars and mechanical toys, which clearly are not living, can do both. Plants, which are living, appear to do neither. Similarly, it is sometimes not easy to decide whether a living thing is still alive. Raw fruit and vegetables are still alive when they are eaten. Seeds may look completely lifeless but, when provided with appropriate conditions, may germinate and grow into new plants.

It is generally accepted that living things display, or have the capacity to display, certain characteristics which can be called ‘processes of life’. This is what makes them different from things which never live.

THE PROCESSES OF LIFE

Some processes of life are more obvious and easy to understand than others. In explaining some of them it is difficult to avoid using the term ‘cell’. Nearly all living things are made up of one or more distinct, very small units called cells. Consideration of the cellular organisation of living things will help more able, older children to understand the nature of all life processes.

Reproduction

The process which makes living things fundamentally different from nonliving things is their ability to reproduce. There are two types of reproduction: sexual and asexual.

In sexual reproduction life begins in a new individual when two specialised types of cell (called gametes) join together. In animals the male gamete is a sperm cell and the female gamete an egg cell (see here). In flowering plants the male gametes develop inside pollen grains and the female gametes inside structures called ovules (see here). When male and female gametes join together a single-celled structure called a zygote is formed. The zygote will contain genetic material (‘instructions’) from both parents.

‘Asexual’ means ‘without sex’, and gametes are not involved in asexual reproduction. New individuals begin their existence by growing whilst attached to their (single) parent and then become separated and live independently. Familiar examples of this are provided by spider plants and the bulbs of daffodil plants. Some simple animals can reproduce asexually but humans and other vertebrates cannot.

Growth

Living things grow and develop, increasing in size and changing shape as they progress towards a mature body form. Growth in the tiny organisms consisting of a single cell results in that cell getting bigger. When it reaches a certain size the cell divides into two, each of which is smaller than the parent (i.e. the cell reproduces asexually). These cells grow until they are as big as the parent was and then they in turn divide. Growth in organisms whose bodies are made up of many cells requires repeated cell divisions. All humans begin life as a single cell. When fully grown we have millions of cells in our bodies.

All parts of an animal’s body can grow, whereas growth in plants is restricted to specific regions such as the tips of shoots and roots. Plants also grow throughout their lives whereas animals have specific growth phases and usually stop growing once they attain a particular size. In humans this is at about 18-21 years of age but in most other animals it is at a much younger age. Although animals stop growing bigger some of their cells continue to divide. Cells which wear out quickly, for example skin cells and red blood cells, are continually being replaced. Some other types of cell, including muscle and nerve cells, cannot be replaced.

As organisms get bigger, structures develop to support them, for example the trunks and branches of trees and the skeletons of animals. The word ‘skeleton’ is most often used to refer to the bones found inside vertebrate animals. It is worth noting that invertebrate animals also have a skeleton. Some, like insects and crabs, have a hard outer covering which supports them. Soft-bodied invertebrates, like earthworms and jellyfish, are supported by the liquid or jelly-like material inside their bodies (see here).

Feeding

Living things need food for growth and energy. The food of humans and other animals comes from other living things. Animals eat food containing complex chemicals that need to be broken down into simpler ones by digestion before being reassembled into the chemicals their own bodies need (see here). In contrast, plants take in simple chemicals and turn these into the more complex chemicals they need. In green plants, the process of photosynthesis is very important – carbon dioxide and water are turned into sugars using energy from sunlight as ‘fuel’ (see here).

Movement

To obtain their food or to escape from danger, most animals need to be able to move around. This can involve swimming, wriggling, crawling, flying, hopping, walking or running. They use muscles to do this and, if the animal has a rigid skeleton, the muscles are attached to it. Some animals cannot move from one place to another, for example adult barnacles and mussels. These animals rely on food being brought to them by the water around them. Parts of plants are able to move, for example leaves and petals, but plants do not need to move around because the chemicals they need are all around them – in air, soil and water. Movement of plants is usually due to some cells dividing faster than others or to cells becoming bigger or smaller by taking in or losing water.

Sensitivity

Finding food, a mate and a suitable place to live requires animals to be sensitive to their surroundings and show appropriate behaviour patterns. Plants also need to respond to their environment; for example, they must make sure that their shoots grow upwards and their roots grow downwards. In animals it is the sensory part of the nervous system which detects change in the environment. The sensory cells are often gathered together in groups to form sense organs such as eyes or ears (see here). As well as these sense organs humans have sensory cells scattered throughout their skin and internal organs. These detect pressure, pain, heat and cold. The information collected is passed to the brain which controls how we react (behave) as a result of this knowledge. Any resultant change in behaviour involves our muscles (we might run away if we saw an angry bull), or our endocrine (hormone) system (we might stand our ground but start to sweat with fear).

Plants do not have nerve cells or a brain. They often produce minute amounts of chemicals which help them to respond to their environment. For example, if a plant is placed so that its shoot is bending away from the light a chemical collects on the lower side of the stem. The cells there divide more rapidly so that the shoot becomes upright and then bends towards the light.

Respiration

Energy is needed to keep all life processes going. It comes from a process called respiration which, in most cases, requires a supply of oxygen that is obtained by breathing. Oxygen is needed because during respiration food is slowly ‘burned’ to release the energy in it. When something burns, it is combined with oxygen.

Respiration occurs in all living cells and it is important to remember that plants as well as animals need to ‘breathe’. Breathing is more obvious in animals because they need more energy than plants, for example when moving, and hence need to respire more quickly. Larger animals need to have a system for moving oxygen, food and other substances around the body to their cells; this is provided by their circulatory system.

Excretion

The processes which occur inside living cells result in useful products being made, for growth, repair and maintenance, for example. By-products which are not needed and which may be dangerous to the organism are also made. The removal of these is called excretion. Carbon dioxide and urea (a component of urine) are examples of by-products which are excreted by animals. Defecation is not an example of excretion. This is because the faecal material has never entered body cells. Faeces are undigested food material that remain inside the alimentary canal (the tube that carries food through the body) until they are got rid of by defecating.

SUMMARY

- Defining what is meant by life is not easy; one way of doing it is to identify those things which living things do that most non-living things are unable to do.

- Seven main ‘characteristics of life’ can be identified: the most important of these is reproduction.

- The others are growth, feeding, mov...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 Life Processes

- 2 Humans as Organisms

- 3 Green Plants as Organisms

- 4 Variation and Classification

- 5 Living Things in Their Environment

- 6 Materials and Their Properties

- 7 Natural Materials: the Story of Rock

- 8 Electricity

- 9 Forces and Motion

- 10 Light

- 11 Sound

- 12 The Earth and Beyond

- Glossary

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Primary Science by Jenny Kennedy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.