![]()

1

The Psychosocial Dynamics of Cyber Security

An Overview

Stephen J. Zaccaro, Reeshad S. Dalal, Lois E. Tetrick, and Julie A. Steinke

To state the very obvious, computers and computerized systems reside at the core of work in organizations today. Such systems are the primary conduit for information flow and exchange in organizations. They are used to organize, regulate, and in many instances synchronize work, particularly “knowledge work” (Davenport, 2005; Davenport, Jarvenpaa, & Beers, 1996; Reinhardt, Schmidt, Sloep, & Drachsler, 2011), among organizational members. Moreover, access to the Internet has exponentially increased connectivity across organizational boundaries. Accordingly, specialists in computer systems and information technology (IT) have become critical to organizational functioning.

The ubiquity of computer-based information systems in organizations, and the greater connectivity they foster, has also increased organizations’ vulnerability to external intrusion into information infrastructures. Accordingly, cyber crime has soared, increasing 96 percent over the last five years (Ponemon Institute, 2010, 2014), and has become very costly to organizations (e.g., Sony Corporation, 2015). This heightened vulnerability has increased the number and importance of personnel in organizations who have the responsibility for increasing the security posture of their firms and, when attacks do occur, providing the comprehensive detection, remediation, and recovery responses necessary to restore that posture (Alberts, Dorofee, Killcrece, Ruefle, & Zajicek, 2004; Cichonski, Millar, Grance, & Scafone, 2012; West-Brown et al., 2003). Indeed, as Zaccaro, Hargrove, Chen, Repchick, and McCausland note in Chapter 2 of this volume:

As one indicator of this surge, the membership of incident response teams in the professional organization Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams … has nearly doubled in the last five years.…Moreover, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has newly created a division dedicated to cyber crime and has elevated the cyber threat to the number three national priority. (p. 14)

Given the centrality of information systems in organizational work and the costs of cyber attacks to organizations, maximizing the work effectiveness of cyber security personnel should be a critical organizational priority. Improvement of cyber security performance can take place along two broad avenues. One involves using automated and technological strategies to increase the strength of infrastructure security and facilitate cyber incident handling. The complexity of information systems and the unmanageable onslaught of data that cyber professionals need to monitor mandate the use of such strategies. For example, millions of events can come across the screen of a network monitor on a typical day (Grance, Kent, & Kim, 2004; NRI Secure Technologies, 2014). Software such as ARCSIGHT (http://www8.hp.com/us/en/software-solutions/arcsight-esm-enterprise-security-management/index.html) is used to sift through these numbers, pulling out the suspicious events whose signatures suggest that more extensive review is needed. Such systems reduce the cognitive load on the incident monitor to a level where the task of incident detection can be reasonably and successfully performed.

The promise of automated strategies in maximizing efficiency and reducing errors often makes them the dominant and preferred approach to cyber security performance enhancement. However, such strategies need to be integrated with those defining a second avenue of performance improvement—psychosocial strategies that target the human element of cyber security. These strategies seek to maximize the human capital organizations can deploy to protect against cyber attacks and to improve their information infrastructures. Such capital can take, for example, the form of knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) that contribute to effective cyber security performance. Psychosocial strategies can also include management and team enhancement tools that facilitate not only individual performance but also the collaboration activities often required by the complexity of cyber work (Osorno, Millar, & Rager, 2011; see also Zaccaro et al., this volume). These strategies also include establishing functional work designs and calibrating organizational structures to align them more closely with the changing cyber security operating environment. Taken together, these strategies are a necessary complement to the technology and automation strategies used to enhance cyber security performance. Indeed, one long- established premise in organizational psychology is that changes in technological systems must be carefully integrated with changes in social systems; failure to do so can result in the impairment and collapse of both systems (Trist & Bamforth, 1951).

Research on cyber security performance, however, has generally favored technical over psychosocial approaches. For example, Ahmad, Hadgkiss, and Ruighaver (2012) noted recently that

much incident response literature consists of industry white papers that outline recommended (technical) practices for implementing an incident response capability in organisations.…The fact that incident response research focuses on a technical view and gives relatively less attention to holistic socio-organisational perspectives is consistent with trends in information security research as a whole. (p. 643)

Pfleeger and Caputo (2012) pointed to the negative consequences of implementing technological solutions to enhance cyber security without considering the social and behavioral dimensions of such solutions. For example, they noted how users can perceive security technology more as an “obstacle” when requests are made for behavior changes (e.g., mandatory password changes) and often “may mistrust, misinterpret, or override the security” (Pfleeger & Caputo, 2012, p. 598). Other researchers have noted the failure to understand the link between technology and human capacities. For example, Parasuraman and Manzey (2010) indicated that “research has shown that automation does not simply supplant human activity but rather changes it, often in ways unintended and unanticipated by the designers of automation” (p. 381). In Chapter 12 of this volume, Coovert, Dreibelbis, and Borum speak to similar themes. These researchers point to how the strong and growing role of technology in the cyber security domain is fundamentally changing the roles of humans in this same domain without systematic attention being devoted to understanding these role shifts.

At the team and organizational levels, efforts to enhance cyber security performance are also heavily weighted toward technological considerations. Researchers have established a set of technical skills and procedures that contribute to effective performance and developed process models of how such performance should occur (e.g., Alberts et al., 2004; Cichonski et al., 2012). However, relatively less attention has been devoted to socio-organizational aspects of cyber security work. For example, whereas process models can elucidate the flow of incident response work, such work processes involve a considerable number of judgment and decision points that are susceptible to a range of biases (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Effective incident handling also utilizes a number of cognitive processes—such as situational awareness, complex problem-solving, divergent thinking and creativity, and adaptation (Mumford, Mobley, Uhlman, Reiter-Palmon, & Doares, 1991; Mumford, Schultz, & Van Doorn, 2001)—that would also not be fully reflected in incident response process models. Cyber security performance may also be influenced by an array of nontechnical KSAs and other attributes as well as team dynamics and a number of other contextual variables (see Jose, LaPort, & Trippe, Chapter 8, this volume).

This lack of balance between technical and psychosocial perspectives suggests a need for greater understanding of how these two perspectives can be better integrated and aligned to produce a more comprehensive approach to cyber security. That is the purpose of this book. We have drawn on the science of industrial and organizational (I/O) psychology to (a) understand the unique challenges of cyber security work, (b) provide insight into work processes and dynamics specific to cyber security, (c) elucidate drivers of effective performance in this domain, and (d) provide the basis for enhancing such performance. Our overall goal is to help maximize the human element in the integrated sociotechnical system that comprises the cyber security domain in all organizations.

One might ask, why not simply and directly apply what is already known about work enhancement from the I/O psychology literature? Why does the domain or context of cyber security need special coverage? We believe that cyber security work contains aspects that mark it as somewhat different from other types of work. These aspects are noted in several chapters in this book, so we only summarize them here. First, cyber security work perhaps integrates technological and human elements more than many other forms of work. IT systems represent both the tools and the focus of such work. This greater entwinement of human and technological systems creates different kinds of performance requirements, as noted in the aforementioned chapters. Second, cyber security, particularly incident response and handling, entails a threat-oriented reactive posture (Bronk, Thorbruegge, & Hakkaja, 2007; West-Brown et al., 2003). This posture emphasizes particular work characteristics—such as monitoring and vigilance, threat handling, and complex problem-solving—with successful performance defined as recovery to a secure status quo (rather than enhancement of a particular process or outcome, although these too can be elements of cyber security performance). Also, the consequences of failed performance can be widespread and/or devastating. Such characteristics are characteristic of other work domains, including the military, nuclear system regulation, air traffic control, fire and rescue, police, and emergency medicine as well as jobs related to natural and man-made disaster preparation and response (Steinke et al., in press). However, in most of these work domains, the ratio of action-oriented to knowledge work is higher than it is in cyber security. In the latter, the work to be completed is mostly knowledge work, in which cognitive loads may be relatively higher, requiring greater deployment of different cognitive resources in response to threats.

This difference points to a third separation between cyber security work and other work domains. Most of the aforementioned domains entail some level of performance adaptation, defined as “cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral modifications made in response to the demands of a new or changing environment, or situational demands” (Baard, Rench, & Kozlowski, 2014, p. 50). Given the high turbulence in the cyber security operating environment, with the constant evolution and novelty of both technology and the nature of incoming threats, we would argue that the adaptation requirements may be even higher in this work domain than in most others. Zaccaro, Weis, Chen, and Matthews (2014) argued that adaptive performance requirements can also vary in terms of their cognitive, social, and emotional loads, with significant implications for the particular KSAs required for effective performance, along with the requisite training strategies to foster these KSAs. They argued that adaptive readiness, or an “individual’s readiness to adapt to changing operational and environmental contingencies” (p. 94), depends upon identification of the right load balance among cognitive, social, and emotional performance requirements and implementation of training regimens that match this balance. We have noted that the typical or “routine” work of cyber security carries a higher cognitive load in general; we would add on the basis of these arguments that adaptation in this domain imposes higher cognitive demands than are characteristic of other domains.

There are other unique aspects of cyber security work that differentiate it from other forms of work; however, the combination of high person–technology work interface, threat-focused knowledge work, and the need for high adaptive cognitive-oriented readiness suggests that work performance models in this domain will vary significantly from those in most other work domains. The chapters in this book were invited to provide some insight into these models. Our authors include a mix of scientists who are well versed in either cyber security technology, I/O psychology, or both. Their contributions provide an integrated framework for understanding the work of cyber security.

Overview of the Chapters

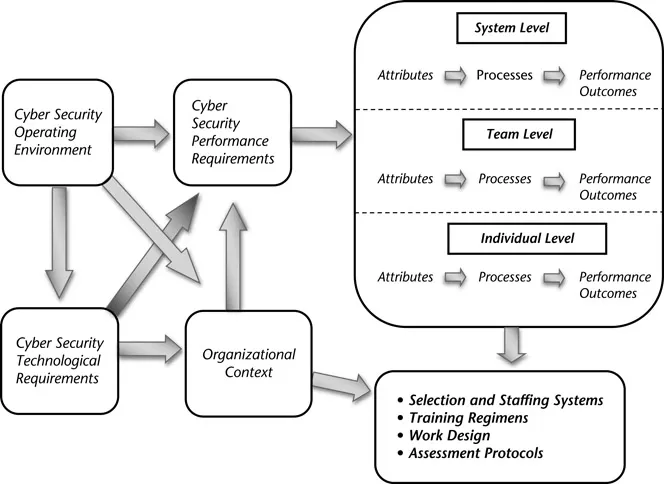

One means of approaching this book as a whole and its chapters is to consider a traditional performance enhancement model widely used in I/O psychology (e.g., Campbell, Dunnette, Lawler, & Weick, 1970; Dunnette, 1963; Ghiselli, Campbell, & Zedeck, 1981; Zaccaro, 2001). This model, shown in Figure 1.1, indicates that the environmental context of cyber security—with its constantly changing threat profiles, evolving technology, and shifting national and international priorities—influences (a) cyber security technological requirements; (b) cyber security performance requirements; and (c) organizational contexts, particularly in terms of decisions about cyber security infrastructure, functional structure and departments within an organization, and cyber security policies. Technology requirements also influence, in turn, cyber security performance requirements and elements of the organizational context. The decisions made by organizations regarding their cyber security posture also influence the performance requirements to be addressed by cyber security personnel.

This combination of environmental factors, technological and performance requirements, and organizational context provides the foundation for specification of the attributes and performance processes that lead to performances outcomes. The model in Figure 1.1 depicts these links between attributes, processes, and outcomes as occurring at three levels within the cyber security infrastructure—individuals, teams, and systems. At the individual level, attributes are KSAs and other personal qualities that contribute to effective enactment of performance processes. Processes are those cognitive and behavioral activities enacted to meet performance requirements and produce outcomes (Campbell, McCloy, Oppler, & Sager, 1993). At the team level, attributes include team composition (Mathieu, Tannenbaum, Donsbach, & Alliger, 2014) and team emergent states (e.g., trust, cohesion, collective efficacy; Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001) that influence the collaboration and interaction processes used to accomplish team-level work and produce team-level outcomes. Systems can refer to multiteam systems (Mathieu, Marks, & Zaccaro, 2001) or to other collectives larger than single teams. System attributes are compositional and emergent states at the larger system level and the relationships among different component teams and elements. As at lower levels, such attributes influence system-level processes and performance outcomes.

Figure 1.1 A Model for Enhancing Cyber Security Effectiveness

The attributes, processes, and performance outcomes at multiple levels provide the basis for strategies and interventions to improve performance (Goldstein & Fo...