1

Introduction: The Temporal Relations of Conceptualization

All the psychological schools and trends overlook the cardinal point that every thought is a generalization; and they all study word and meaning without any reference to development.

—Lev Vygotsky, Thought and Language, 1934, p. 217

Metaphors strongly influence scientific inquiry, biasing our models and the questions we ask. Historically, metaphors for the human brain have ranged from “mechanical like a clock” to telephone switchboards and digital computer systems. Recently, some computer scientists have suggested that we study human-computer interaction in terms of how the “wet computer” (the human brain) is related to the “dry computer” (programs and hardware). Although such talk may have a place, it is scientifically a questionable guide for either appropriately using today’s computer programs or inventing more intelligent machines. In particular, to move beyond present-day programs to replicate human capability in artificial intelligence, we must begin by acknowledging how people and today’s computers are different. We must ground and direct our inquiry by the frank realization that today’s programs are incapable of conceiving ideas—not just new ideas—they cannot conceive at all. The nature of conceptualization is perhaps the most poorly grasped of all cognitive phenomena we seek to explain and replicate in computer systems.

At least since the 1980s, an increasing number of cognitive scientists have concluded that if we are to understand the variety of behavior in people and other animals, and indeed how complex reasoning is possible at all, we must reformulate the computational metaphor that has been the basis of our very successful models of human knowledge and problem solving. We must reformulate the very idea that knowledge consists of stored data and programs. We need a theory of memory and learning that respects what we know about neural processes. Rather than the idea that the brain is a wet computer, we need another metaphor, less like a clock or calculator and more like how biological systems actually work.

Most present-day computer models of human thinking suggest that conceptualizing involves manipulating descriptions of the world and behavior in a deductive argument. In these models, concepts are like defined words in a dictionary and behaving like following recipes in a cookbook. In this book I explore the idea that conceptualizing is more akin to physical coordination. For conceptualizing to serve reasoning, it cannot be made up of the products of thought— words, definitions, and reasonable arguments—but must be of a different character. Conceptual coordination refers to how higher-order neural processes (categories of categories) form and combine, and especially how they relate in time.

In this introductory chapter, I argue that fundamental ideas about what memory is and how it works are at issue. I illustrate the idea of conceptualization as coordination in terms of a distinction between simultaneous and sequential processes. Subsequent chapters in Part I reveal how conventional programming languages have biased psychological theories of memory, to the point that what the brain accomplishes is both taken for granted and under-appreciated.

1.1 THE ESSENTIAL IDEA: MATCHING AND COPYING VERSUS ACTIVATING IN PLACE

In this book I explore the hypothesis that so-called procedural memory (often called serial learning in the psychological literature) is at the neural level quite unlike stored procedures in a computer’s memory. By a procedure, I mean any ordered sequence of behaviors, including habits; carrying out mathematical algorithms such as long division; and speaking in regular, grammatical sentences. In the theory I develop, such procedures are always reconstructed and never just rotely followed.

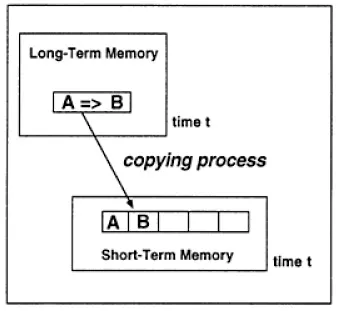

According to prevalent scientific models,1 human memory is something like a library. When a particular memory is needed, an internal librarian goes off to the right shelf and brings out the book for you to read. By the conventional model of memory, you get the whole book delivered at once, as a piece—it was stored intact, unchanged from the last time you put it away. In this conventional account of memory, procedural knowledge is like a recipe, with the steps written out in advance and stored off to the side until they are needed (Fig. 1.1).

In the example shown in Fig. 1.1 a “production rule” in long-term memory, “A implies B,” matches the current contents of short-term memory (A). In the “remembering” process, B is copied into short-term memory, which is a special place for storing copies of information so that it can be read and modified (this place is called a buffer or set of registers). By copying from long-term memory, the rule that “A follows B” can be attended to and followed by a computer program. The memory librarian, a special program inside the computer, finds information by several methods: by the location where it is stored (e.g., like the Dewey decimal system), by the name associated with the memory (e.g., the title of the information), or by the contents of the memory (e.g., as indexed by a subject catalog). By this view, knowledge consists of structures stored in long-term memory, which are indexed, retrieved and copied by the librarian when needed.

Fig. 1.1. Conventional, stored structure view of memory. Remembering is retrieving by matching and copying text into a “buffer” or “register.”

In general, symbolic cognitive modeling of the 1950s through the 1980s assumed that this computational process is literally what happens in the brain: Human remembering is copying descriptions into short-term memory. Human thinking consists of manipulating the copy, not the long-term memory. When a person formulates a new idea or learns a new procedure, a description is copied back to long-term memory. By this view, remembering, thinking, learning, and memorizing are different processes, occurring at different times, using different structures located in different places. Indeed, many scientists have believed that, when we reason, these memory operations repeatedly search, copy, and revise a memory store. Thinking is a process of manipulating copies of structures retrieved from memory; learning is a process of selectively writing associations back into long-term memory. Consequently, the terms search, retrieve, and match are prevalent throughout the cognitive psychology and artificial intelligence literature (e.g., see Shapiro, 1992).

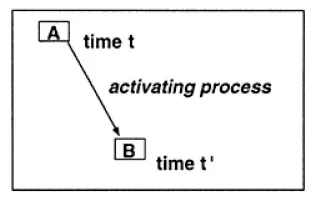

In the theory of memory I develop in this book, each “step” in our behavior physically activates the next step (Fig. 1.2). I call this a process memory. In the simplest case, process memory consists of only one thing being active at a time (A at Time t, B at the next point in time, t’). That is, the working memory has only one element at a time (compare to the buffer in Fig. 1.1). (I hope the reader is skeptical about terms like thing and point in time, as these are terms that we must become precise about.) For working memory to contain multiple ideas (both A and B, or more generally 7±2 ideas, as descriptive models suggest), there must be an additional capability to hold A active while B is active. We often take this capability for granted. How is it possible that more than one idea can be active in a neural system at one time? As I show, questioning how memory actually works leads to additional important questions about the evolution of neural architecture and a better understanding of what consciousness accomplishes.

By the view I am developing, supported by recent research in cognitive neuroscience, working memory is a series of activations becoming active again, wherever they might be located in the brain. Instead of copying the “contents” of memory, a physical process is simply reactivated in place. A is associated with B not because a descriptive statement like “A implies B” is stored in memory, but because the structure constituting the categorization, A, physically activates the structure constituting the categorization, B. This is the essence of the connectionist or neural network approach. (Chapter 3 provides details about how categorizations may be formed as neural maps.)

Fig. 1.2. Association by sequential activation in time.

In this simplest form of activation (Fig. 1.2), A (designating some categorizing process) is active at Time t, but not at Time t’. The relation “A activates B” is not logical in the sense of the meaning (“A implies B” or “if A then B”), but strictly temporal in the sense of sequential events—the activation of B follows the activation of A. At a lower level, some neurons involved in A’s activation are contributing to B’s activation at Time t’. But in an important sense, in the simplest forms of sequential activation the physical structure called A only exists as a coherent structure at Time t.

Metaphorically, activation of a structure is something like a meeting of people: The group only exists as a unit when the meeting is occurring. Individuals might potentially belong to many groups and hence participate in other kinds of meetings at other times. But (in this metaphor) a given group structure only acts as a physical unit when a meeting is occurring. In this simple view, A and B are two groups of neurons, such that A only exists as a physical structure when group A is “meeting” (i.e., activated together) and B does not exist at this time. But the activation of A at Time t tends to activate B next, at Time t’, as if one meeting is followed by another.

I said that the relation “A activates B” is not logical. Logical relations are higher-order categorizations, or learned relations, not part of the neural mechanism of memory. By assuming that the units of memory are logical associations (“if A then B,” “A causes B,” “A is a kind of B,” “A contains B,” “B follows A,” etc.) many symbolic theories of memory impose the content and organization of higher-order, conscious behavior (called reasoning) onto all levels of knowledge. Paraphrasing Bertrand Russell, they suggest that “it is logic all the way down.” By this view, logical associations are stored as whole “if-then” structures (Fig. 1.1), called production rule memory.

I am suggesting that when we think “A implies B” we are constructing a higher-order categorization involving the idea of implication itself (just as causes, kind of, and next step are higher-order ideas). That is, the relations of logic are categorizations that indicate how other categorizations (ideas) are related. More fundamental, simpler associations form on the basis of temporal relation alone; namely, Categorization A activates Categorization B (Fig. 1.2).

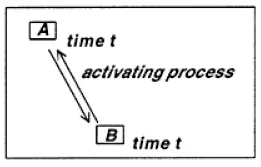

Now that we are considering temporal relations, another possibility becomes apparent: Structures may exist together by virtue of activating each other at the same time. Fig. 1.3 shows that A and B activate each other simultaneously; this is called a coupling relation.

Fig. 1.3. Simultaneous activation. Association by activation at the same point in time (coupling).

1.1.1 Activation Trace Diagrams

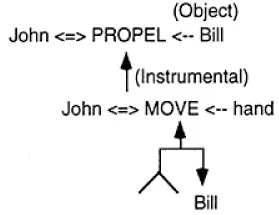

The nature of networks in computer programs and how network diagrams are interpreted provides another way of understanding the distinction between conventional stored memory and a process memory. Consider how a diagram representing a conventional cognitive model depicts a network with concepts and relations (Fig. 1.4). Mathematically, the network is a special kind of graph. By this view, a memory is a network that exists independently, off by itself, stored in a repository, like a note on a piece of paper or a diagram in a book. For example, in the representation of the sentence, “John hit Bill with his hand,” the categorizations “John,” “Bill,” and “hand” all exist as physical structures at the same point in time and are related by other, primitive, categorizations: PROPEL, MOVE, “object,” “instrumental,” and so forth. To remember that “John hit Bill with his hand,” this theory of memory claims that you must store such a structure in your long-term memory. Again, the conventional view is that the structure is stored as a whole, connected thing and is retrieved as a unit unchanged from its form when put away. (With rare exception, forgetting is not incorporated into symbolic models of memory, just as learning is not inherent —occurring at every step—in most symbolic models of behavior.)

Fig. 1.4. Conventional view of memory as a static network. Conceptual dependency representation of “John hit Bill with his hand.” PROPEL and MOVE are conceptual primitives with an actor designated by a double arrow

. (Adapted from Encyclopedia of Artificial Intelligence, Shapiro, 1992, p. 261. Copyright ©1992. Reprinted by permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.).

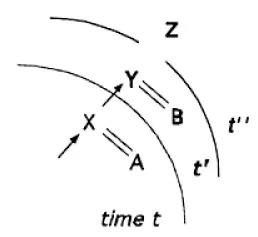

Less commonly in the computational modeling literature, one finds diagrams that show a “trace” of processing events occurring in time. This is the kind of diagram I frequently use in this book (Fig. 1.5). In this activation trace diagram, three time periods are represented, designated t, t’, and t”. Each letter in the diagram designates a categorization, a physical neural structure. In the example, categorizations X and A are active and activating each other (a coupling). X activates Y, such that at the next point in time, t’, Y is active. Also at t’, B is active and coupled to Y. Most important, at Time t’, as shown here, structures associated with X and A are no longer active; in some important sense they do not exist. If they are reactivated, they will have a different physical form. Only Y and B exist at Time t’. Finally, at Time t” Z becomes active and Y and B do not exist. In chapter 10, I show how such diagrams better explain grammatical behavior than the static, nonsequential view of conceptual relations in a parse graph (Fig. 1.4).

Fig. 1.5. Activation trace diagram—neural processes activating each other sequentially in time

and coupled neural processes (X=A, Y= B). Shading suggests that Time

t is in the past, so connections are weakening or no longer active.

1.1.2 Categorized Sequences

In considering the neural basis of procedural memory, we need one more activation relationship, namely the idea of a

categorized sequence, more commonly called a

chunk (

Fig. 1.6). C is a higher-order categorization, subsuming the sequence

. In physical neural terms, C is a neural map that in some way activates and is activated by X, Y, and Z. In semantic terms, C is a kind of

conceptualization. Exactly how the neurons are related in categorizations X, Y, Z, and C is not clear. I present various possibilities in this book. By the meeting metaphor, C is a group in a meeting that contains or influences a sequence of other meetings (X, Y, and Z). The point of the diagram is to show how categorizations may be related temporally by a kind of physical inclusion process called

subsumption. That is, C physically exists as an active structure starting at Time t and persists through Time

t”, X, Y, and Z are activating at the points in Time

t, t’, and

t”, respectively. C physically contains (subsumes) X, Y, and Z. In Part II, I reexamine a variety of cognitive phenomena to tease apart how this physical activation relation works, especially how...