- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Differences

About this book

This text reviews the mass of information concerning the ways in which individuals and groups differ from each other. Reviews of research findings and interpretations are provided on: physical appearance, performance and health; cognitive abilities; personality; and development across the life span. Extensive treatment of foundations (historical, measurement, research methods, biological, social, and cultural) is also provided. Both normal and abnormal behaviors are considered. The book provides an interdisciplinary focus, including material from all the behavior and natural sciences, not just psychology, sociology, or biology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Origins and Developments

Human beings may look alike, act alike, and think alike, but in one way or another everyone is different from everyone else. People differ not only in physical characteristics such as weight, height, hair and skin coloring, and facial features, but in their abilities, personality, and behavior as well. Even identical twins, who have identical heredities, are not exactly alike. They may appear initially like two peas in a pod, but on further acquaintance the two peas are seen to possess a number of dissimilarities. People are born different, and in many ways they become even more dissimilar as they grow older.1 These differences enable us to distinguish among people, thereby serving as a basis for differential treatment of friends, acquaintances, and strangers.

Some futurists fantasize a world populated by armies of clones that would presumably be easier to train and control than the masses of individuals now inhabiting our planet. But in addition to being uninteresting, such large-scale conformity of appearance and action might very well result in mass extinction when conditions or circumstances changed radically and the clones did not possess the physical structures or abilities to deal with the changes.

From a Darwinian perspective, some individual differences, such as birth defects or physical disorders, decrease the chances of survival and reproduction. Other differences contribute to the individual’s likelihood of surviving and perpetuating his or her own kind. The occurrence of severe climatic or environmental changes may pose a test of the survival value of individual characteristics. For example, introduction of a new strain of viruses or physicochemical conditions that individuals lack the necessarily equipment to deal with can easily decimate a population. This would seem less likely to occur, however, in a population consisting of individuals possessing a wide variety of physical and behavioral characteristics.

A vast array of individual differences in structure and functioning can be found both within and between various plant and animal species.2 From single-cell organisms at one extreme to whales and giant sequoias at the other, a wide range of sizes, shapes, and other characteristics can be observed. For example, there are both inter- and intraspecies differences among mammals in speed, strength, agility, emotionality, intelligence, and other behaviors. A common pastime among boys is to rank different animals on their aggressiveness and which ones would be most likely to win in a fight. Are lions better fighters than tigers? Are grizzlies better fighters than Texas longhorn steers? A similar game played by comparative psychologists has been to rank different animals on their intelligence. Over 2,000 years ago Aristotle attempted to rank different animal species on a scale of intelligence—a so-called scala natura. Many centuries later, G. W. Romanes (1883), the father of comparative psychology, made extensive comparisons of the learning abilities and other psychological characteristics of different species of animals. The intelligence of a variety of animals (crabs, fishes, turtles, dogs, cats, monkeys, human infants, etc.) was also studied by E. L. Thorndike (1898/1911). Thorndike initially believed that earthworms have absolutely zero intelligence and hence are at the bottom of the intelligence scale. However, after observing that earthworms could learn a simple maze after many trials, Thorndike concluded that they have some intelligence after all. Many other interspecies comparison studies of the abilities of animals to perform cognitive tasks such as problem solving and thinking were subsequently conducted by psychologists and biologists.

As interesting as comparisons of animals’ abilities may be, this book is limited to the description and discussion of human differences, both within and between demographic groups. Within this restricted domain, attention is given to biological, psychological, and social differences and how those differences affect human behavior. The approach, however, is holistic, recognizing that the physiological, cognitive, and behavioral characteristics manifested by individual humans do not act alone but rather interact in shaping a particular person.

First and foremost, this book emphasizes the uniqueness of the individual. Although the body and mind of a given person operate according to the same natural principles or laws as those of other people, everyone is a unique whole in his or her own right. Consequently, the uniqueness or individuality, as well as the general biological and psychosocial principles that apply to all people, must be taken into account to obtain a clear understanding of why a person behaves in a certain way.

INDIVIDUALISM

The social theory of individualism, which maintains that the highest political and social value is the welfare of the individual, goes back at least to ancient Greece. According to this doctrine, people should be free to exercise their self-interests through independent action. In contrast, advocates of collectivism believe in centralized socioeconomic control.

Greek philosophers such as Plato (C. 427–347 B.C.) and Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) advocated individualism in thought and action and had much to say about human differences. As described in the Republic, Plato’s ideal state was one in which people are selected, perhaps by means of aptitude tests, to perform tasks for which they are best suited. Aristotle’s interest in individual and group differences was revealed in his comments in the Ethics and Politics concerning gender and ethnic differences in mental and moral characteristics. Like their successors, however, Plato and Aristotle realized the need to place limits on human behavior. Whenever the goals of the individual conflict with those of the society of which he or she is a member, social disharmony is the result. The writings of 20th-century psychologists also point out the problems of unbridled individualism. Although it is not synonymous with egoism, or extreme self-centeredness, individualism can lead to feelings of alienation, loneliness, worthlessness, depression, and other symptoms of mental or behavioral disorders. Psychologists recognize that a stable sense of individual identity develops not from preoccupation with the self but rather from cooperative and supportive interactions with other people.

The emphasis on individual abilities and rights that characterized Athenian democracy did not persist through the Middle Ages in Europe. Until the revival of Greek culture and thinking during the Renaissance, prevailing political, social, and religious forces emphasized autocratic control. The individual was seen first and foremost as a member of a group or class (e.g., the peasantry, clergy, nobility, artisans, etc.) and inseparable from it. Rather than being a person who happened to perform a particular occupation, an individual’s identity was viewed as synonymous with the role prescribed for members of that occupation (Fromm, 1941).

The Middle Ages was a time of unquestioning faith and a struggle to survive and do one’s duty toward the church and state. Earthly existence was merely a preparation for Heaven—a reward that would come only from neglecting the self and practicing obedience toward God and accepted social institutions. However, the 16th century witnessed the beginning of a gradual return to the ancient Greek perspective on the value and worth of the individual. The growth of capitalism and the attendant Protestant ethic stimulated the belief that every person is to some extent separate from others and self-sufficient. Unlike the deterministic “veil of tears” perspective that prevailed in the Middle Ages, the philosophy of life during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment periods was that individuals can influence their situation and circumstances. Freed from the constraints of intolerance and censorship, people can use their abilities to understand themselves and the world in which they live. Such knowledge can then be applied to improve one’s situation and that of other people.

Traditional, nativistic theological doctrine had held that life is a battle between good and evil—that people are born in sin and hence basically evil with only a hope and not a guarantee of salvation and a happy afterlife. In contrast, philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke, and Voltaire saw human beings not as innately bad but rather as being made bad by the social circumstances in which they exist. According to this idea, if you want to shape or change an individual’s behavior, you must control his or her social environment.

Individualism flourished particularly in 18th- and 19th-century Britain, France, and the United States of America. The democratic political structures of these countries, which emphasized freedom and equality (in theory if not always in fact), contributed to that growth.3 Sustaining this individualism by freeing people from the shackles of poverty and disease were the industrial, scientific, medical, and educational advances of the time. These advances put health, wealth, and wisdom in the hands of more people, allowing them to realize their desires and achieve whatever they would. The self-made man, who attained wealth by his own efforts rather than by inheritance, became more common and widely admired. It was thought that, given sufficient drive and ambition plus a bit of luck, all things were possible.

SCIENTIFIC BEGINNINGS

The 19th century was a time of rapid developments in the natural sciences—notably astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, and geology. Furthermore, developments in mathematics and engineering provided methods and tools for the growth of both pure and applied science. Emerging from progress and issues in the physical and biological sciences was a new scientific psychology.

The Personal Equation and Reaction Time

In 1795, Maskelyne, royal astronomer at the Greenwich Observatory in England, became concerned when he discovered that his own observations of stellar transit times did not agree with those of his assistant, Kinnebrook. When Kinnebrook failed to correct this error, Maskelyne concluded that his assistant lacked the ability to make accurate determinations of stellar transit times, and so poor Kinnebrook was discharged. The matter might have rested there if it had not come to the attention of the astronomer Friedrich Bessel at Königsburg two decades later. After examining the data from the Greenwich Observatory and making additional observations of his own, Bessel concluded that rather than being due to simple mistakes by Kinnebrook, the disagreement between the two astronomers was caused by individual differences in their response times. In other words, each man was filtering his sensory experiences—in this case, the time required for the passage of a star between cross-hairs on a telescope—through his own unique personal equation. Correcting for the personal equation of an observer became the practice in astronomy during subsequent decades. Invention of the chronoscope did away with many of these errors of observation in astronomy, but the concept of a personal equation continued to be of interest to physiologists and psychologists during the latter half of the 19th century. Numerous studies of variations in the personal equation with sense modality (vision, audition, touch, taste, smell, etc.), stimulus intensity, and other conditions were conducted.

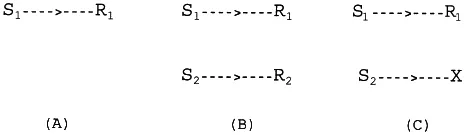

Investigations of the personal equation by psychologists took the form of reaction time experiments, studies of so-called mental chronometry. These studies were concerned with determining the time required for various mental processes by application of a subtractive procedure. As described by the Dutch physiologist Frans Donders and illustrated in Fig. 1.1, the procedure involved the measurement of three different kinds of reaction time. To measure Donders’ A (simple) reaction time, a single stimulus (S1) is presented; the subject is told to make a specified response (R1) to the stimulus as rapidly as possible. To measure Donders’ B (choice) reaction time, one of two different stimuli (S1 or S2) is presented; the subject is told to make one specified response (R1) to one of the stimuli (S1) and another specified response (R2) to the other stimulus (S2). To measure Donders’ C reaction time, one of two stimuli (S1 or S2) is presented; the subject is told to make a specified response (R1) to only one of the stimuli (S1) and ignore the other stimulus. After completing a number of trials using each of the three procedures, three mean reaction times—A, B, and C—are computed. Next three derived times are determined: baseline, identification, and selection. Reaction time A is referred to as baseline time, the difference between reaction time C and reaction time A is identification time, and the difference between reaction time B and reaction time C is selection time. These three times vary with the individual, the sense modality, and other conditions under which they are determined.4

Innumerable investigations employing Donders’ procedure were conducted at Wilhelm Wundt’s (1832–1920) Leipzig laboratory and elsewhere during the late 19th century to determine the time for certain mental events. Unfortunately, these studies, which also employed the method of introspection (a “looking into” one’s mind and reporting on subjective impressions) failed to confirm the validity of Donders’ method for this purpose. However, the Donders method and extensions of it are still widely employed. One extension is S. Sternberg’s (1969) additive factors method, which breaks down total reaction time (RT) into a series of successive information-processing stages (also see Biederman & Kaplan, 1970).

FIG. 1.1. Diagrams of Donders’ Type A, B, and C RT experiments: S1 and S2 are Stimuli 1 and 2, R1 and R2 are Responses 1 and 2, and X is no response.

Sir Francis Galton

Psychology was formally established as a science in 1879, the year when Wundt founded the first psychological laboratory in the world in Leipzig, Germany. Rather than psychology being devoted to the study of individual differences, Wundt maintained that it should be concerned with the discovery of general facts and principles pertaining to the function...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Origins and Developments

- 2 Measurement and Research Methods

- 3 Biological Foundations

- 4 Sociocultural Foundations

- 5 Physical Appearance, Performance, and Health

- 6 Theories, Concepts, and Correlates of Cognitive Abilities

- 7 Exceptional and Special Cognitive Abilities

- 8 Personality Theories, Concepts, and Correlates

- 9 Personality Problems and Disorders

- 10 Differences Across the Life Span

- Glossary

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Differences by Lewis R. Aiken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.