- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of American English

About this book

This impressive volume provides a chronological, narrative account of the development of American English from its earliest origins to the present day.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of American English by J.L. Dillard,J. L. Dillard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Historical & Comparative Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

On the background of American English

English came to North America and what eventually became the United States as a part of the general movement of European languages and their speakers not only to the one ‘new’ continent but to almost all parts of the world. The type of English spoken during the period of exploration and colonization was important to the history of American English. So were the languages spoken by other groups – immigrants and native Americans. The first point has received recognition from the beginning of the study of American English. The second has tended to be overlooked.

The first officially English-speaking group came to the Americas in the 1497 expedition of John Cabot under a patent from Henry VII. Its leader, Genoese-born Giovanni Caboto (whose name was also spelled Tabot and Chabot in various documents), had been in the spice trade in the Middle East before the expedition in which he ‘discovered’ and named Newfoundland. His son Sebastian, whose strengths and weaknesses as an explorer have been much discussed and debated, was as internationally oriented as the father. English came to the New World in a context of language contact, and language contact is the salient feature of its early history.

There are theories of European presence in the area preceding Cabot, and even Columbus, to complicate an already complex picture. At any rate, it was not long before that presence increased greatly. Axtell (1988: 145) reports that ‘By 1517 “an hundred sail” could be found in Newfoundland’s summer harbors. The discovery of the Great Banks in the 1530s only increased the traffic between Europe and America.’

The speculation about pre-Columbian exploration includes the possibility that early fishermen sailing from Breton or even from Bristol may have sought the rich catches of cod and other fish of which Sebastian Cabot is supposed to have reported that they were so thick as to impede the progress of his ships. The speculations themselves have little to do with the early history of American English; the fishermen, it now seems, a great deal.

It was an Englishman perhaps less complicated than either John or Sebastian Cabot, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, who, after at least one failure, founded the first relatively permanent settlement of what might simply be called English speakers. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, however, his ‘mixed’ colony consisted of ‘raw adventurers, landsmen, and sailors’. The possibilities concerning this first English-speaking colony are fascinating, but documents do not seem to be available.

For all the European migrants to the New World there was a complex language contact situation presenting historical problems which are hardly solved by facile statements about communication by signs and chains of interpreters. (For the latter, the fascinating problem is still the first link in the chain.) When Verrazzano complained that in his last contact with North American ‘natives’, in 1524, he suffered because ‘we could converse with the bad people (mala gente) only by signs’ (Sauer 1971: 61), we might wonder how he had communicated with the presumably contrasting ‘good people’. Considerations of maritime language history may cause one to wonder what language(s) Captain John Hawkins used in his voyages ‘capturing negroes on the Guinea coast and [selling] them to the Spaniards at the point of his sword’ (Lowery 1959: 89) as well as visiting the French in Florida on his second voyage in 1564.

Perhaps of even more linguistic significance, in view of Bakker (1987), is the early prominence of Basques. Fishing ships also engaged in trading for pelts, said to have visited the shores of Maine, included Basques who visited the Fagundes colony (Sauer 1971: 61). Whalers of that nationality have been reported as early as 1536 (Axtell 1988: 146) or even earlier according to some (see Bakker 1987: 2). L’Escarbot (1609: 172) reported:

For to accommodate themselves with us, they [the native Americans] speake unto us in the language which is to us more familiar, wherein is much Basque mingled with it: not that they care greatly to speake our languages; for there be some of them which do sometimes say, that they come not to seek after us: but by long frequentation they cannot but retain some word or another.

Bakker (1987: 4) theorizes that a ‘Basque Nautical Pidgin may perhaps be a missing link between a Portuguese Proto-Pidgin (or the Lingua Franca) and Creole languages all over the world’. The most important maritime contact languages of the exploration period, with a few changes, may have been involved in the early period.

At any rate, ‘one of three Basque–Icelandic vocabularies preserved in manuscript’ (Bakker 1987: 1) Contains

ser ju presenta for mi ‘what do you give me?’

where the use of for seems to be a marker of an oblique (‘beneficiary’) case. The same text also contains another expression, fenicha for you, where fenicha represents an obscenity quite typical of frank sailor badinage, in which for seems to mark a direct object. In Schuchardt’s (1909) Lingua Franca materials, per, a virtual Romance equivalent of for, may precede a pronoun in either direct or indirect object function (see also Harvey, Jones and Whinnom 1967). Schuchardt’s examples include

mi mirato per ti ‘I have seen you’

mi hablar per ti ‘I say to you’

and there is a parallel, with a slight phonological change, in the contact variety of Italian used in Ethiopia (Bakker 1987: 27)

non dire ber luy ‘don’t tell him’.

Holm (1989, II, 629) cites Afrikaans vir and Indo-Portuguese per in the same functions.

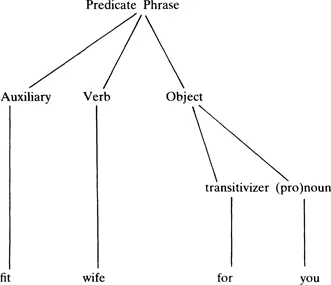

A directly parallel use of for seems to exist in English nautical pidgin of the same general period, here used in the African slaving trade, as attested by William Smith, A Voyage to Guinea:

This fit Wife for you.

Although Smith (or his printer) capitalized Wife in accordance with the general usage of the time, when nouns were so capitalized, an analysis of this wife as a verb would fit better into Pidgin English structure – something about which neither Smith nor his printer may have known. The preceding sentence of the quoted African’s discourse, This no my wife, clearly contains a nounal use of wife in a negated zero copula predicate. A pidgin context, at least, seems established.

Where Smith, and most English readers, quite probably interpreted:

The Pidgin English interpretation is more naturally:

Fit replaces more ordinary English (the term is borrowed from Taniguchi 1972) can in certain West African English pidgins today and may have done so very early. By the time of P. Grade (1892) the usage seems to have been well established. Grade gives the examples:

| Me no fit for help me alone | ‘I cannot help myself alone’ |

| Me no fit lie | ‘I cannot lie’. |

The first of Grade’s citations is from ‘ein eingeborener aus Bagida, Mensa’; the second, from ‘ein Kruneger, Friday’.

The interpretation that a ‘noun’ or other part of speech may serve as ‘verb’ (or predicator) is at least possible in much of the pidgin literature of about the same time. The missionary periodical The Religious Intelligencer, published from the 1820s, has forms like

O, how I sorry for him

where the description of sorry as a predicator, although not that favoured by an approach which tries to make the pidgin as close to ordinary English as possible, is at least feasible. The same page of the text contains a more probably adjectival use of sorry:

(I am) only sorry ‘cause can’t read Bible

and two occurrences of the noun form:

(I) love tell him [Jesus] all my sorrows

He [Jesus] take away all my sorrows

Such variability, especially between Pidgin English forms and more standard forms, is commonplace in these texts.

Aside from its evidence about the origins of some Pidgin English structures, the Basque nautical pidgin seems to have had some significance for the total language picture of early North America, perhaps not only on the northern shores (see Chapter 5.) For the more northerly area, L’Escarbot (1609: 268) reported about ‘our French-men, and chiefely the Basques who doe go euery yeare to the great riuer of Canada for the whales’ with a ‘confusion’ of nationalities which only serves to emphasize the multinational (and multilingual) nature of the fishing and trading fleets. It was these Basques, apparently often identified with seagoing Frenchmen as ‘Normans’, about whom L’Escarbot reported (1609: 172):

Whereof the [Canadian] Savages being astonied, did say in words borrowed from the Basques, Endia Chave Normandia, that is to say, that the Normans know many things. Now they call all Frenchmen Normands [sic] except the Basques, because the most part of the fishermen that goe fishing there, be of that nation

which a transmissionist would almost immediately take for a Lingua Franca-related text.1

Early contact with the Basque pidgin seems to have been extensive. A text presented in an unpublished (1986) paper by Bakker (quoted in Holm 1989, II, 629) is

for you mala gissuna ‘you are a bad man’.

Variant forms of Basque gizon (‘man’) occur in North American varieties, notably kessona in a Basque–Amerindian pidgin studied by Bakker (1987, ms.). Goldin, O’Leary and Lipsius (1950) have gazoony, said to be characteristic of ‘mid-West prisons’ and to mean ‘a degenerate, especially a passive pederast; a punk’. Wentworth and Flexner (1975) have gazooney, gazony (‘An ignoramus, Maritime’) with no indication as to date. They also have ‘A young hobo; an inexperienced or innocent youth. Hobo use’.2

Mala, in the text cited by Bakker, is obviously Romance. Another form cited in the same text, gara, seems likely to be from something like Spanish guerra (ultimately from Germanic), and the mixing of Romance forms (cf. chave above) from different languages is a commonplace feature of the maritime communication situation. (See Chapter 5, especially in the Gulf Corridor situation.)

Accretions to the vocabulary in the early contact area came from such sources. Scargill (1977: 25–6) specifies that ‘a Portuguese farmer or llavrador in 1499 explored our [i.e. the Canadian] coast and gave the name of his trade to Labrador’. The early fishing activities brought terms like baccalaos (‘codfish) and capelin, (a small fish), named by French fishermen because of a fancied resemblance to the European capelan, and penguin from Welsh. The words referred to here probably came, however, more directly from maritime activity than from the languages cited as etymological sources, at least in any traditional sense of borrowing.

Terms not rated ‘Americanisms’ by the esoteric standards of the branch dictionaries were also heard along the coastline. Barcalonga for ‘a large … fishing-boat … common to the Mediterranean’ (Oxford English Dictionary, citing Falconere, Dict. Marine, I, 89) is first listed from 1682. The term is attested in the Americas, used in the Portobello/Bastamentos area, in a kind of journal (anonymous) of Bartholomew Sharp’s privateering expedition quoted from a 1752 manuscript by Jameson (1970: 89). Pontillo (1975) lists uses of barca and congeners but not barca longa. Barque longo is attested as early as 1680;such non-Spanish (and non-Iberian) forms are considered Lingua Franca by Pontillo (1975) and by Harvey, Jones and Whinnom (1967). The Dictionary of Americanisms records Barkentine or Barquantine as ‘a name applied in the great lakes of North America’. Maritime forms obviously went far in the Americas.

For the originally maritime variety Pidgin English, recognition has come late – and not necessarily from the most orthodox sources; Mario Pei, whose very name has tended to be opprobrious among linguists, has perhaps the most complete presentation (1967). Perhaps even less prestigious among linguists was Edgar Sheppard Sayer, whose Pidgin English (1939/43) attracted a scathing review from Hall (1944), ironically one of the most active linguists in discovering and publicizing the widespread existence of pidgin and creole languages. Sayer asserted, perhaps more from personal experience than as the result of professional analysis, that Thirty million people speak Pidgin English’ (1939/43: 1).

Sayer also asserted the uniformity of Pidgin English: ‘fundamentally Pidgin English does not change as it leaps from continent to continent, island to island. Local custom determines the slight variations in the words used and their meaning’ (1939/43: 80). Any attempt to follow his contention that one who could speak the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Longman Linguistics Library

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 On the background of American English

- 2 Early diversity, levelling and rediversification

- 3 The development of Black English

- 4 The development of Southern

- 5 The early history of the Gulf Corridor

- 6 Westward, not without complication

- 7 Regionalization and de-regionalization

- 8 Derealization: the small town, the city and the suburbs

- Bibliography

- Subject index

- Dialect index