![]()

Part II

Specific Disorders

![]()

4

Major Depressive Disorder

Paula Truax

Pacific University

DESCRIPTION OF THE DISORDER

Depression is one of the most common reasons that people seek mental health care. It is also one of the most frequent and expensive mental health problems across the United States. From 5% to 9% of women and 2% to 3% of men meet criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) at any one time; from 10% to 15% of women and 5% to 12% of men will experience MDD at some point during their lives (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Not only is depression experienced by a significant number of people, it may also have a chronic impact on those who experience it. Between 50% and 60% of those with one episode of depression will have a second episode; 70% of those with two episodes and 90% of those with three episodes will have another episode (APA, 1994).

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. (DSM-IV; APA, 1994), MDD is characterized by a constellation of emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physical symptoms (Table 4.1 for DSM-IV diagnostic criteria). There are four basic elements to a diagnosis of MDD. The first is presence of the hallmark emotional symptoms of MDD: sadness and anhedonia. At least one of these emotional symptoms must be present most of the day nearly every day for a minimum of 2 weeks. Although necessary for diagnosis, these mood symptoms are not sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of MDD. The second component is presence of behavioral and physical concomitants, such as sleep difficulties, appetite or weight changes, psychomotor changes, and fatigue, as well as cognitive symptoms of worthlessness or guilt, difficulty concentrating, and suicidal ideation. Note that most of the symptom areas are multidimensional and may be coded as present whether the symptom has significantly increased or decreased. Thus, there can be great diversity among different people who meet the MDD diagnosis. The third necessary component is that symptoms must lead to clinically significant distress. That is, clients must be experiencing notable difficulties in their social, familial, occupational, or recreational life as a result of these symptoms. Finally, it must be determined that symptoms are not better accounted by a diagnosis other than MDD. Common psychological conditions that should be ruled out when determining whether a client meets criteria for MDD are Bipolar Disorder, Dysthymic Disorder, Bereavement, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD).

TABLE 4.1

Diagnostic Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder | A. Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent and change from previous functioning. At least one of the five is number 1 or number 2. 1) Depressed mood most of the day nearly every day 2) Markedly decreased interest or pleasure most of the day nearly every day 3) Significant increase OR decrease in weight or appetite nearly every day 4) Insomnia OR hypersomnia nearly every day 5) Psychomotor agitation OR retardation observable by others nearly every day 6) Fatigue OR loss of energy nearly every day 7) Feelings of worthlessness OR excessive guilt nearly every day 8) Difficulty concentrating OR making decisions nearly every day 9) Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide |

B. The symptoms do not meet criteria for a Mixed Episode (significant manic symptoms). |

C. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning. |

D. The symptoms are not due to a substance or general medical condition. |

E. The symptoms are not better accounted for by Bereavement. |

MDD and Bipolar Disorder differ in one important way: presence or absence of manic symptoms. Any person meeting full criteria for MDD with a history of even one diagnosable manic or hypomanic episode should be diagnosed Bipolar Disorder I or II rather than MDD.

Dysthymic Disorder and MDD differ in two important ways: Dysthymic Disorder is milder and longer lived than MDD. In contrast to MDD’s “most of the day, nearly every day” for 2 weeks requirement, Dysthymic Disorder requires “more days than not” for 2 years. If a client meets full criteria for current or past MDD, a Dysthymic Disorder diagnosis will not ordinarily be made. One important exception is that when a full 2 years of Dysthymic Disorder precedes the initial MDD episode, a comorbid diagnosis of MDD superimposed on Dysthymic Disorder may be given.

MDD should also be differentiated from disorders that represent reactions to extreme events such as Bereavement and PTSD. Bereavement and MDD often appear similar and involve similar symptoms. The key difference is that bereft individuals have experienced the loss of a loved one to death within the preceding 2 months and their symptoms are directly related to the consequences of the loss. When symptoms do not begin abating 2 months postloss and/or they are more severe than would typically be seen with Bereavement (e.g., psychosis, extreme feelings of worthlessness or generalized guilt, significant suicidal ideation), a diagnosis of MDD should be considered. MDD also has a symptom profile similar to PTSD (e.g., loss of interest, sleep difficulties, difficulty concentrating), yet PTSD is unique from MDD in that it requires (a) the presence of a recent or past trauma (e.g., rape, natural disaster, childhood sexual abuse), (b) intrusive visual, emotional, or sensory memories of the trauma, and (c) active attempts to avoid thinking about the trauma. Therefore it is essential to assess significant life events and their role in the client’s current symptoms for differential diagnosis in MDD.

The distinction between GAD and MDD is a subtle one. Some argue that they are two variants of the same construct (Burns & Eidelson, 1998). Still, there are some key differences in symptom profiles and prescribed treatments. Like MDD, GAD involves difficulty concentrating, fatigue, and difficulty sleeping. Unlike MDD, GAD’s hallmark symptom is excessive and inappropriate worry about most issues in daily living. People with GAD find it difficult to stop worrying and relax. Because some evidence suggests that people who meet criteria for both MDD and GAD may be less amenable to standard treatments for depression (Bakish, 1999), it is important to evaluate the extent to which worry dominates the depressive symptoms.

Although the DSM-IV s categorical distinctions are far from perfect, a growing body of literature on empirically supported interventions suggests that accurate diagnosis can enhance treatment, whereas inaccurate diagnosis hampers treatment. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, for example, is the most researched and the most supported therapy for MDD. In contrast, when the depression is severe or involves a manic component, psychotropic intervention should be part of the treatment plan. Similarly, when anxiety or avoidance dominates the client’s presentation (e.g., PTSD, GAD), exposure interventions should be incorporated into treatment (see Nathan & Gorman, 1998, for a summary of treatments and empirically supported interventions).

METHODS TO DETERMINE DIAGNOSIS

Two commonly used methods for determining a diagnosis of MDD are the clinical interview and the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-Clinician’s Version (SCID-CV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Wlliams, 1997). Unstructured clinical interviews are the most frequently used, but also the less reliable of the two (First et al., 1997). Essential factors in increasing the reliability of the typical clinical interview are the clinician’s knowledge and systematic application of that knowledge during the diagnostic portion of the interview. Minimum knowledge areas include the following:

• Diagnosis of MDD: DSM-IV symptoms of MDD, time-frame (2 weeks), and severity (e.g., most of the day, nearly every day)

• Differential diagnosis: DSM-IV symptoms of other mood disorders and other diagnoses that may appear like MDD (e.g., GAD, PTSD, Bereavement, Adjustment Disorder with Depressed Mood)

Application of this knowledge requires the following:

• Asking specifically about each of the symptoms, time-frame, and severity

• Asking specifically about key symptoms from other diagnoses.

An example of how the diagnostic portion of the clinical interview may begin follows:

| Therapist: | Now I would like to ask you some fairly specific questions about how you have been feeling recently. I know you said that you have been feeling depressed and that it has been going on for about two months. Has there been a two-week period in the past month in which you felt depressed most of the day, nearly every day? |

| Client: | Yes, I have felt depressed most of the day, nearly every day for the past two months. |

| Therapist: | Okay. Can you tell me if the past two weeks have been characteristic of the past two months. |

| Client: | If anything the most recent two weeks have been the worst. That is why I came to see you. |

| Therapist: | OK then, let’s focus on the most recent two weeks for the rest of these questions. [Establishing time frame] In the past two weeks, have you also lost interest or pleasure in things that you usually enjoyed? [Checking out specific symptoms] |

| Client: | Yes. |

| Therapist: | Has that been most of the day, nearly every day? [Severity] |

| Client: | It has been constant. I can’t get interested in anything. |

| Therapist: | How about your weight and appetite? You mentioned earlier that you have gained twelve pounds in the past month because you are eating all the time due to depression. Did I get that right? [Time-frame, specific symptoms, severity] |

| Client: | Yes; I understand some people lose weight when they feel depressed. I wish that were me. |

| Therapist: | Depression is different for everyone. Weight gain is not uncommon. You also mentioned earlier that you have been having difficulty going to sleep; has that been nearly every day over the past two weeks? [Time-frame, specific symptoms, severity] |

| Client: | It has been every day over the past two weeks. [Interviewes continues asking about all symptoms, time frame, and severity] |

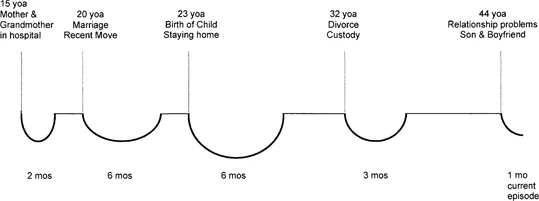

Once the therapist has asked about the symptoms of MDD and ruled out other diagnoses, a timeline may be drawn of the client’s MDD history to assess the role of events and possible comorbidity with Dysthymic Disorder (p. 388, DSM-IV, APA, 1994). See Fig. 4.1 for MDD timeline of the case presented later.

The SCID-CV (First et al., 1997) is a semistructured interview for assessing the major DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses. The SCID-CV is a simplified version of the SCID Research Version designed to be more appropriate for the clinical environment. It is divided into modules (Mood Episodes, Psychotic Symptoms, Psychotic Disorders, Mood Disorders, Substance Use Disorders, Anxiety and Other Disorders) that can be used independently or as a comprehensive diagnostic interview. The Mood Episodes and Mood Disorders modules take about 20 minutes to administer. Administration time for the entire SCID-CV is approximately 90 minutes. The primary advantages of the SCID-CV over the less structured clinical interview are that it is more reliable and it prompts the interviewer to ask the appropriate diagnostic and differential diagnostic questions.

FIG. 4.1. Genevieve’s Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) timeline (yoa, years of age; mos, months).

ADDITIONAL ASSESSMENTS REQUIRED

Medical Consultation

A thorough assessment of MDD should always involve a physical examination to determine potential physiological factors that may be causing or exacerbating the client’s condition, such as thyroid problems, infections, toxic chemical levels, liver disease, cancer, or vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Such an evaluation is doubly important when a client is either taking or wishing to take psychotropic medication.

Self-Report Instruments

There are numerous self-report instruments for depression. Any measures selected should be practical, relevant, in common use, reliable, valid, and consistent with case conceptualization, treatment plan, and goals. Both symptomatic assessment and cognitive-behavioral assessment are presented in the following sections.

Symptom Measures

Depression Symptoms. The Beck Depression Inventory: Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is one of the most commonly used self- report inventories for assessing depression severity. The BDI-II is a 21-item measure corresponding to the DSM-IV symptoms of depression. Each item is rated from 0 to 3, and completion time is approximately 5 minutes. Scoring and interpretation involves totaling the item scores and comparing the total score to the severity cutoffs in the BDI-II manual (0–13 = minimal; 14–19 = mild; 20–28 = moderate; 29–63 = severe). The BDI-II demonstrates good internal consistency with coefficient alphas of .93 and test-retest stability over 1 week (r = .93, p < .001). Discriminant and construct validity have been demonstrated with higher correlations between the BDI-II and depression measures than between the BDI-II and anxiety measures (see Beck et al., 1996, for a review of the psychometric proper...