![]()

Explosives and Hazardous Compounds Used in Ordnance 1

Try to learn something about everything and everything about something

Thomas Henry Huxley

Introduction

Understanding how military ordnance operates and functions requires a basic understanding of energetic and other hazardous compounds. Explosives, propellants, pyrotechnics, pyrophorics, and other reactive substances are used extensively in ordnance to provide different effects. In addition to propelling or fragmenting a munition, these materials are used to arm fuzing systems, deploy payloads, illuminate the night, and track trajectories; as well as energize power sources for fuzing, steerable fins, guidance systems, and other functional purposes.

The military has unique requirements due to the extreme environments in which ordnance is used. For example, in the United States, all materials required to make an explosive must be available in the lower 48 states, which ensures availability and deters reliance on foreign sources. Other unique considerations include bullet impact sensitivity, reactivity with other materials, hygroscopicity, and long-term stability in storage.

This chapter introduces the basic principles and unique attributes of energetic and other hazardous materials used in military ordnance. It is divided into eight sections:

• Terms and Definitions

• Introduction to High Explosives

• High Explosives—Groups

• High Explosives—Configurations and Effects

• Introduction to Low Explosives and Propellants

• Low Explosives and Propellants—Groups

• Low Explosives and Propellants—Effects and Configurations

• Pyrotechnics, Incendiaries, Pyrophorics, and Smoke Producing Compounds

Terms and Definitions

The definitions provided here are fundamental considerations associated with energetic and hazardous compounds. Additional information on terms, definitions, and abbreviations may be found in Appendices B, C, D, E, and the Bibliography.

Hygroscopicity: The tendency of a material to absorb moisture from the air. The introduction of moisture may affect the sensitivity or stability characteristics of an energetic material.

Reactivity: Energetic materials may chemically react and create other substances when in close proximity to different materials.

Sensitivity: How an energetic material reacts to heat, shock, or friction.

Stability: All explosives decompose over time. Temperature, moisture, pressure, and time contribute to decomposition and stability of energetic materials. Compounds that decompose slowly are sought for military applications.

Toxicity: Most energetics are toxic to some degree and present inhalation, absorption, and ingestion hazards.

Introduction to High Explosives

Much of the information contained in this text focuses on chemical and mechanical explosions. A few definitions relevant to high explosives are provided below and additional definitions and abbreviations are available in Appendices B, C, D, E, and the Bibliography.

Explosion: A sudden, violent release of energy.

Detonation: A chemical reaction that propagates a self-sustaining shockwave that proceeds the reaction zone through the unreacted material at greater than the speed of sound.

High Explosive (HE): A chemical composition capable of detonating when properly configured and initiated. The defining factor between a detonation and explosion; is speed, measured as the velocity of detonation (VOD). It is important to note that all explosives explode, but only high explosives can detonate.

Velocity of Detonation (VOD): The speed at which a self-sustaining shockwave propagates through an explosive composition at a velocity greater than the speed of sound in that material. Factors affecting the VOD include; explosives chemistry, density, temperature, geometry, purity, and method of initiation. VOD is measured in feet per second (fps) or meters per second (mps).

High-Explosive Performance Characteristics

Common terms associated with high-explosive-filled munitions:

High-Order Detonation: When the high explosive charge performs correctly, the munition “high ordered.”

Brisance: Determined by the detonation pressures generated, brisance addresses the shattering capability of a high explosive. An explosive with a fast VOD is more “brisant” then one with a slower VOD.

Sympathetic Detonation: When the detonation of one munition is caused by the explosive shockwave from another in close proximity.

Low-Order Detonation: When the high explosive charge partially detonates or does so at an insufficient velocity. Possible causes include, poor chemistry or manufacturing techniques, contamination, insufficient initiation, or explosives deteriorating over time. A munition low-ordering, results in additional hazards such as, damaged and burned explosives and munition components littering an area.

High Explosives—Groups

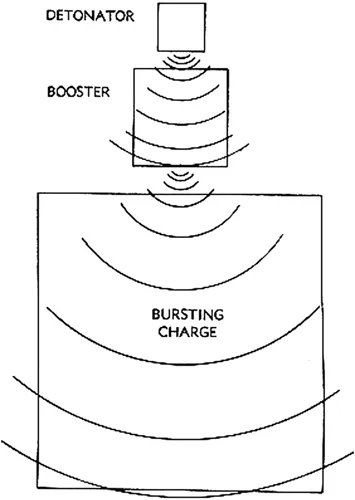

High explosives are broken into three groups: primary, secondary, and main charge explosives. For a munition to function as designed, explosive components from all three groups are arranged in order of decreasing sensitivity. Referred to as an explosive train, this configuration allows the incorporation of fail-safes in ordnance designs (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Basic high explosive (HE) firing train. Depending on design and explosives used, the booster in the center may not be required. (From U.S. Military TM.)

Every country utilizes a variety of high explosives in ordnance. Due to the vast number of possible compositions, a few examples of explosives used in ordnance by many countries are listed below. However, in literature there is much conflicting information, the VODs of pure explosives listed here are cited from Explosives 6th Edition (Meyer, Kohler, Homburg, 2007). VODs of blended and other explosives are from various sources and listed as “approximately” due to variation dependent upon mixture ratios. Additional information on explosives from each group is available in Appendices D, E, and the Bibliography.

Primary Explosives: Are the least powerful, but most sensitive of the three groups.

Characteristics include:

1. Will not burn, but will detonate, and are very sensitive to initiation from the heat of an electrical source or flame, the shock of mechanical impact, or the friction of two surfaces rubbing together.

2. Provide enough energy to reliably initiate less sensitive secondary explosives.

3. Used in primers, detonators, initiators, leads, relays, and other fuzing components.

Examples:

Lead Azide: Commonly used in modern ordnance.

• Color ranges from white-buff to gray.

• VOD of pure lead azide 14,800 fps (4,500 mps) @3.8g/cm3.

• Moderately hygroscopic. Reacts with copper to form extremely sensitive cupric azide. For this reason, it is usually loaded in an aluminum housing.

• Other names include: Lead Hydronitride (U.S.), Azoture de Plomb (France), Bleiazid (Germany), Chikka Namari (Japan), and Acido di Pimbo (Italy).

Lead Styphnate: In use since WWI.

• Color ranges from yellow, orange to reddish brown.

• VOD, 17,000 fps (5,200 mps) @2.9g/cm3.

• Slightly hygroscopic.

• Other names include: Trinitrorescorcinate de Plomb (France).

Note: The initiating efficiency of lead styphnate is poor but is easily initiated by flame. Lead azide is more difficult to initiate by flame, but a good initiator. Because of the ease of initiation of lead styphnate and the initiating efficiency of lead azide, a combination of the two has been used in blasting caps and detonators since 1920.

Mercury Fulminate: Widely used until replaced by lead azide and lead styphnate.

• Color ranges from white, light-yellow-brown, or gray.

• VOD, 16,400 fps (5,000 mps) @3.3g/cm3.

• Non-hygroscopic. Reacts with aluminum, magnesium, copper, zinc, and brass.

• Other names include: Fulminate of Mercury (U.S.), Fulminate de Mercure (France), Knallquecksilber (Germany), Fulminato di Mercurio (Italy), Rtutnyy ful’minat (Russia), and Raisanuigin (Japan).

Secondary Explosives: Are usually mixed to make main charge explosives. Characteristics include:

1. Not as sensitive to heat,...