![]()

Part IV

Skill & Control Aspects

![]()

Chapter 11

Basic solutions to the problem of head-centric visual localization

Horst Mittelstaedt

Max-Planck-Institut für Verhaltensphysiolgie

Seewiesen, F. R. Germany

Dedicated to Konrad Lorenz

On the occasion of his 85th birthday and in remembrance of the 1958 Macy Conference.

Preface

If the analysis of an unknown information processing structure is based on a single model, be it chosen because of its rigour, its simplicity, its biological plausibility, historical renown or current acceptance, or simply because it was the first which came to mind, one generally runs the risk of overlooking basic alternative solutions to the problem under study. To guard against this, Rose and Dobson (1985) advocate to first deduce the logical tree of classes of alternative solutions to a given problem. In a contribution to the 1958 Macy Conference on group processes (Mittelstaedt, 1960; cf. also sequelae in Mittelstaedt, 1961 & 1969), I have tried to develop such a logical tree for possible solutions to the problem of head-centric visual localization. This analysis, though in need of some corrections, may still be useful for the ever livelier discussion on this subject (Howard, 1982; Matin, 1982; Mittelstaedt, 1971; Shebilske, 1984; Bridgeman, 1986; Grüsser, 1986; Steinbach, 1987; & Windhorst, 1988), and is here presented in a revised form.

It addresses the problem of how the visual system gains information about the angular deviation of a target with respect to the head median plane, even though the visual axes may change their directions with respect to that plane. Because, very likely, motion perception is processed separately (and rather differently) from the perception of direction, the present analysis is not concerned with problems of movement perception under these circumstances (which are treated by Wertheim in this volume), and hence not with explaining the absence or presence of perceived motion before, during and after saccades, which, under the label of “visual stability,” is sometimes confounded with the above named issue. Although tempted, I refrain from discussing relations with the present literature (beyond some occasional asides) and from comparing the following text with the original, leaving the latter to interest in the past and the former to endeavors of the future.

11.1 Introduction

Neurobiology strives, ultimately, to explain the behavior of an animal in terms of the properties of the cellular elements of its nervous system and the way the elements act upon each other. Ethology, psychology, neurophysiology and neuroanatomy have undoubtedly assembled an immense body of knowledge about the three necessary constituents of such an explanation: the behavioral capability of the system, the function of the neuronal elements, and their structural connections. Yet only in the case of a few comparatively simple performances, such as the proprioceptive control of limb position in mammals, has it been possible to link all three into an hypothesis which could, at least qualitatively, be verified by experiment.

11.1.1 Bottom-up approach

At first sight the straightforward way towards a physiological theory of behavior would be to start from a list of elementary properties and a plan of the anatomical connections of a small group of neurons. If both are sufficiently complete, it should be possible, first, to deduce the way in which the neurons will act upon each other, and then to calculate the processes that will occur in the aggregate. In this way, a list of the behavioral properties of neuronal aggregates would be gained, and then the same procedure could be repeated, treating anatomically related aggregates as elements of a higher order system until the emerging mechanism would encompass the entire animal. With increasing complexity of the system, it might become increasingly difficult to derive the behavior of the system from the behavior of its elements and a given theory of their interaction. However, the fundamental problem lies in the first step of such an approach, in attaining the theory of interaction itself. Given a precise histological plan of an area of the nervous system, how does one find those elements which belong to the same functional unit? Given an exhaustive list of elementary properties, how can those which are relevant for interaction be selected? It appears, then, that knowledge of properties of the aggregate that should be the result of this approach is in fact its prerequisite. In my opinion, it is this methodological handicap of a “bottom-up” approach, rather than lack of special facts or general laws in the contributing fields, that blocks synthesis of a physiological theory of behavior.

11.1.2 Top-down approach

It is necessary, then, to re-examine a method of analysis which starts with the behavior of the entire animal. At first sight, the methodological difficulties of such a “top-down” approach seem prohibitive. Selecting a hypothetical underlying mechanism, the component units of which would be themselves hypothetical, from an uncontrollable number of alternatives, appears to be a matter of intuition at best, rather than of scientific method. I hope to show however that, at least in the limited field of orientation processes, a rigorous and effective analytical method can be developed by application of control theory. I should like to briefly outline the procedure beforehand.

The mechanism underlying a given orientational capability may comprise very many sub-systems and the flow of information among them may be as complicated as possible under existing conditions. Yet if an animal is able to orient itself actively towards its environment, there must be at least one sub-system that provides the animal with information about its relations to the outside, at least one that changes these relations, and at least one process that connects the two. Thus, for any given capability, it will be possible to indicate the sub-systems which are functionally necessary. Once these have been assessed, we shall try to establish an exhaustive list of all those connections between them which produce the capacity under study. Control theory will enable us, first, to formulate these hypothetical alternatives by means of information-flow diagrams and, second, to calculate the behavior of the systems under various conditions. Hence we shall be able to make predictions testable by observation or by experiment. The decisive criterion of this approach is, then, that the information processing structures (IPS; named “Wirkungsgefüge” in the German originals, Mittelstaedt 1954, 1961) which can produce a given capability are arranged into a logical tree of exclusive or inclusive alternatives. Not just one model but a class of IPS’ may thus be falsified at each nodal point of the logical tree leaving that class to further analysis into which the real system belongs.

11.2 Application to visual localization

This methodological approach shall now be employed in the analysis of one of the most intriguing problems in psychophysiology, the capacity for head-centric visual localization.

11.2.1 Basic alternatives

The problem arises from the phenomenon that stationary objects maintain the directions in which we see them, although the retinae, which convey the information, happen to be attached to a mobile part of our head: the eyeballs. Clearly, this is a fundamental problem for orientation systems in general. Its solution is implicit in our much-quoted ability to hit a target under “open loop” conditions, that is without visual feedback about the position of our arm or hand, or in the chameleon’s ability to pre-set the elongation of its tongue according to the distance of the prey, or in the mantis’ ability to strike in the right direction, or in the chicken’s ability to pick up a bit of grain. Hence, I shall try to formulate the problem generally, and then give an exhaustive list of the possible solutions as well as experimental evidence in some special cases.

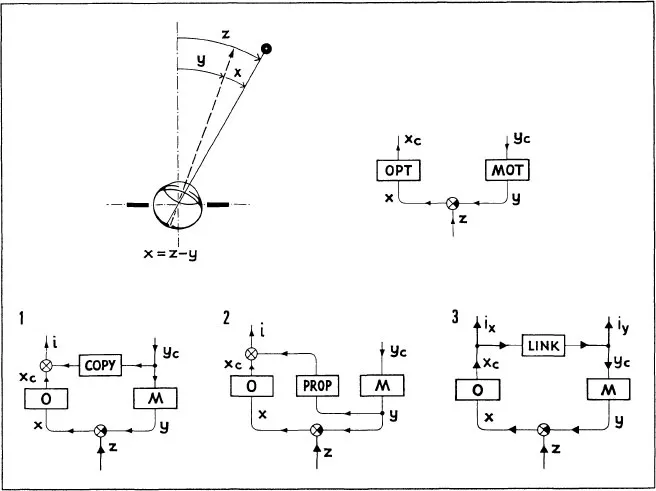

Let us first assess those components of the system which are either factually given or indispensable: They are a sub-system (OPT in Figure 11.1) which measures the position of the target with respect to the sub-system’s coordinates, and a second sub-system (MOT in Figure 11.1) which rotates the sense organ relative to that part of the body with respect to which the target is actually localized. Consider a human subject and, for simplicity’s sake, assume a “cyclopean eye” (or an infinitely distant target). Let the sensory system (OPT) provide information about the angular deviation x of the target with respect to the visual axis, and the motor system (MOT) control the deviation y of the visual axis from the head median plane, both in the horizontal plane. However, the target has to, and can in fact be localized by indicating its deviation z from the head median plane. The core of the problem is, then, that the information available from the sensory input x does not only depend on the variable to be measured z but on the motor output y also. Or in mathematical terms, since

Figure 11.1: Basic IPS’ of headcentric visual localization in the horizontal plane.

Lines signify variables (z, y, z, xc, yc, i), arrows show direction of causality; circles ⊗ addition; black sector ⊗: reversal of sign;

x: angle between target and visual line;

y: angle between visual line and head median plane;

z: angle between target and head median plane;

i: central nervous message which contains information about angle between target and head median plane, and is hence fit to control open-loop pointing;

OPT: optic subsystem measuring x, yielding central nervous signal xc

O: its gain;

MOT: motor subsystem controlled by central nervous signal yc, yielding y;

COPY: subsystem copies motor input yc and adds it to optic output xc;

C: its gain;

PROP: subsystem measures motor output y and adds result to optic output xc;

LINK: subsystem feeds optic output xc back into motor input yc.

In IPS 3, messages ix, iy, which contain information about z, may be taken from xc or from yc, respectively.

the sensory information is

where xc is the output of the sensory (OPT) sub-system, and yc is the input of the motor (MOT) sub-system. The letter O denotes the gain, or more generally the transfer function of the OPT sub-system, and M the gain of the MOT sub-system. This mathematical formulation implies linearity of the entire system. For the sake of simplicity, linearity will be presumed throughout the following. However, although sufficient, it is not always necessary for the capabilities to be discussed, as will be pointed out in detail below.

On these premises, only two fundamentally different solutions are possible: The distorting influence of the efference is eliminated by either making the critical variable i, which yields the desired information about the deviation z of the target, entirely independent of the efference, or by making the efference entirely dependent on the deviation z of the target. In the latter solution, IPS 3 of Figure 11.1, the sensory output xc is fed back to the motor input yc. As we shall see below, the desired information may then indeed be computed from xc or yc. The former solution opens another alternative: Either (as in IPS 1 of Figure 11.1) the motor input yc, or (as in IPS 2 of Figure 11.1) the motor output y is fed forward to the...