- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Reimagining Communication: Experience

About this book

Reimagining Communication: Experience explores the embodied and experiential aspects of media forms across a variety of contemporary platforms, uses, content variations, audiences, and professional roles.

A diverse body of contributions offer a broad range of perspectives on memory, embodiment, time, and more. The volume is organized to reflect a pedagogical approach of carefully laddered and sequenced topics, which supports meaningful, project-based learning in addition to a course's traditional writing requirements. As the field of Communication Studies has been continuously growing and reaching new horizons, this volume presents a survey of the foundational theoretical and methodological approaches that continue to shape the discipline, synthesizing the complex relationship of communication to forms of experience in a uniquely accessible and engaging way.

This is an essential introductory text for advanced undergraduate and graduate students and scholars of communication, media, and interactive technologies, with an interdisciplinary focus and an emphasis on the integration of new technologies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

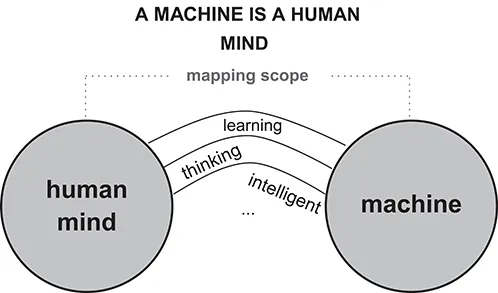

Seeing the World through Metaphorically Coloured Glasses

Introduction

The Essence of Metaphors

The Role of Perception in Creating Metaphors

Our Body—The Source of Metaphors

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Introduction

- Introduction

- 1. Communication, Perception and Innovation: Seeing the World through Metaphorically Coloured Glasses

- 2. Audio Experience

- 3. Re-Imagining Embodiment in Communication

- 4. Reassessing the Importance of Nonverbal Communication in the Age of Social Media

- 5. Prototyping Interaction: Designing Technology for Communication

- 6. Communicating Affect: Face-to-Face and Online

- 7. Synchronicity, or Not: On the Temporal Relations between Journalism and Politics

- 8. Reimagining Memory: Digital Media and a New Polyphony of Memory

- 9. Virtual Space: Palestinians Negotiate a Lost Homeland in Film

- 10. The Mediatization of Politics, Religion, and Science

- 11. Reimagining Audiences in the Age of Datafication

- 12. Youth Media Consumption and Privacy Risks in the Digital Era

- 13. Fan Cultures as Analytic Nexus of Media Audiences and Industries

- 14. From the Ashes of Ubiquity: Selfie Culture as a New Communication Frontier

- 15. Receiving the Stranger Through the Exposed Heart

- List of contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app