eBook - ePub

Psychology and Its Allied Disciplines

Volume 1: Psychology and the Humanities

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Published in 1984, Psychology and its Allied Disciplines is a valuable contribution to the field of Developmental Psychology.Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Psychology and Its Allied Disciplines by M. H. Bornstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 | Psychology and Art |

New York University

INTRODUCTION

One can suppose that the psychology of art began when the first Magdalenian peoples entered the grottos of Lascaux to discover there elaborate realistic wall paintings. How were these people affected by what they saw, and what did those images mean to them? Intriguingly, some Paleolithic animal drawings show signs of having been struck with blunt objects, as if in ritualistic killing. Or, one can suppose that the psychology of art began somewhat earlier when the same peoples actually painted on those cave walls. Why and how did these painters create such art works? Doubtlessly, prehistoric art served religious and social functions, but the quality and surety of these depictions and the fact that some gallery drawings are superimposed on earlier etchings suggest that artistry for its own sake was also involved. Or, perhaps, the psychology of art began when those same painters first thought to depict their ideas or subjects from life around them.

The questions that these earliest art works provoke are the same that arise today when we wander through the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the British Museum in London, or the Louvre in Paris. We wonder what works of art mean to their audience and how works of art affect an audience. We wonder too how and why artists create works that fire our imagination and quicken our feelings. We also wonder what purposes art serves. These questions define and motivate a psychology of art, and the psychological questions art provokes constitute the foci around which this essay is organized.

There are no definitive answers to these questions, however. Art is a mystery. And so the chief aims of this essay are to reraise these questions in the reader’s mind and to organize and discuss psychological opinions about them. The central questions of art endure.

Art is a curious and in many ways paradoxical aspect of life. Humans expend great energy and resources on art, though it seems to be of little biological necessity or relevance. Unlike many things, art must be experienced first-hand—to be told about a painting, a building, or a sculpture is wholly unsatisfying. Art is conveyed in form and content, but the experience of art transcends both; moreover, the subject theme and materials matter, but attention specifically drawn to them can detract from their very effect. Art is private and often wholly idiosyncratic, but it is also largely public—opinion and preference vary in art as much or more than anywhere in human experience, but there is also surprisingly wide consensus. Further, emotion and understanding in art may be coincident or not—one may understand and enjoy a painting, be moved in the absence of comprehension, have insight without feeling, or neither apprehend nor emote in the presence of works of art. The psychology of art must be concerned with all of these contradictory and mysterious dimensions of the art experience.

Outside of art theory and art history and the internal analyses to which they give rise, there are two main intellectual avenues to art and to artistic appreciation or aesthetics. Since aesthetics is defined as a branch of philosophy specifically concerned with the nature of the beautiful, aesthetics is first and prominently identified with philosophy, both in the artistic world and in the lay mind. Philosophical aesthetics is the self-contained study of beauty that derives from speculation, opinion, and judgment based on experience and scholarship. This is an “aesthetics from above” and is the creation of philosophers who grapple with questions about the metaphysical meaning of fine art, the definition, appraisal, and evaluation of beauty, and the language of criticism. However, the constructs it has built on, including shared feeling (Tolstoy, 1898/1962), morality, ethics, sentimentality (Ruskin, 1907), emotion, expression, imagination (Colling-wood, 1938/1958), symbolism (Goodman, 1968), and the like (see Croce, 1909/1972; Margolis, 1962), have for the most part defied operationalism. Doubtlessly, art embraces elements of all of these qualities; it is just that it is difficult to see how the ascription of any one in particular has advanced our thinking about the central questions art provokes.

The major alternative approach to art and to aesthetics, again outside of art theory and art history proper, is through diverse social science disciplines, especially psychology. Psychology is the closest science to art. Broadly, art and aesthetics directly invoke personality, creativity, mentation, and perception—as much as they do theme, style, and technique. Simply put, the art object could not exist without its creator or meaningfully exist without its perceiver. Further, painting is not just a photographic reproduction, but is always a uniquely human interpretation. Finally, painters are unremittingly fascinated with other humans: Stroll through a museum and the salient fact will emerge that portraiture has been the secular obsession of artists. Construed thus, art, artist, audience, and aesthetics clearly fall in the purview of psychology; indeed, art is inextricably entwined with psychology.

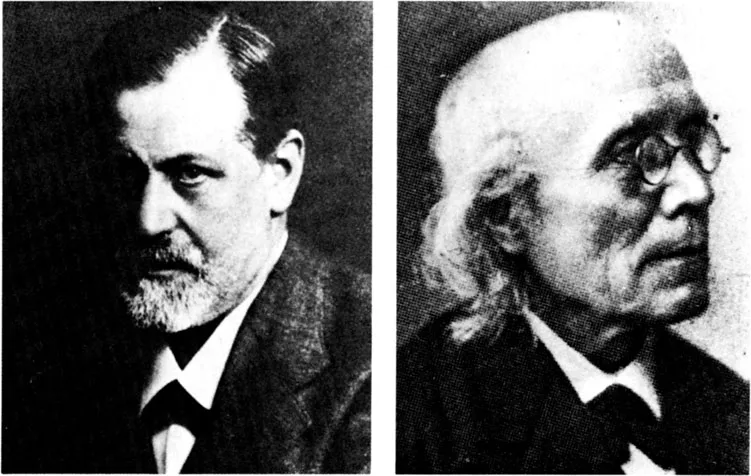

Out of its own pluralistic nature, psychology itself has delimited two principal approaches to creativity, aesthetics, and meaning in the arts: One orientation is scientific and concerns itself centrally with perceptual and cognitive aspects of art, and the other is humanistic and is concerned with emotional and motivational components of art. The two comprise a complementary “aesthetics from below” and represent comprehensive orientations to art. Both are relatively young, having developed as has psychology in the twentieth century. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) established the humanistic orientation. Freud’s insights in art were broad and sweeping; he endeavored to bring art under a general psychological theory of personality. Gustav Fechner (1801–1887) originated the scientific tradition. Fechner’s views about art were focused and narrow; he thought to submit art to experimental analytic investigation in the laboratory. Though these two different paths have led to seemingly different perspectives on art, a panorama of the psychology of art is more detailed and richly textured for their joint efforts.

The oeuvre of the Belgian Surrealist René Magritte (1898–1967) is perfused with pictorial ambiguity and is preoccupied with themes of presence-absence and life-death. Understanding some of his compositions can be informed by clinical knowledge of the artist’s enduring melancholia ascribable to the early death of his mother [Wolfenstein, 1973].

The human mind has a special affinity for pictures. Not only do infants, children, and adults shown pictures for the first time recognize familiar objects [Bornstein, 1984a], but adults can expertly recognize over 2000 different images days after they have seen each only once for one second [Standing, Conezio, & Haber, 1970].

The psychological enterprise in art—humanistic or scientific—is predicated on the utility, acceptability, and meaningfulness of explanation or interpretation in art. Clearly, not everyone subscribes to the idea that understanding art can be advanced through psychological ratiocination. If explanation were not meaningful, then the psychological “enterprise,” as I have called it, would amount to a useless exercise. But I think that it is not, and, as I endeavor to show, in the very short time since psychology was established, the psychology of art has made substantial contributions to elucidating motivation and meaning as well as the effects of formal properties of art. Works of art need to be understood, and they need to be approached via many avenues; art does not undergo diminution when it is submitted to analysis. Psychologists, of course, have been strong on this point; Freud, for example, maintained that “what has not been understood has been inaccurately perceived or reproduced [1914/1963, p. 83].” But artists and connoisseurs too have compellingly argued the case of psychological analysis. Analysis has always proved valuable to artistic fidelity, quality, and creativity. As Pablo Picasso admitted:

FIG. 1. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) and Gustav Fechner (1801–1887). (National Library of Medicine, Washington, DC)

Paintings are but research and experiment. I never do a painting as a work of art. All of them are researches [quoted by Arnheim, 1962, p. 13].

And, the affect and the meaning of art works are augmented, not reduced, by knowledge of the mental and emotional processes they excite. As the respected critic Max J. Friedländer observed:

Art being a thing of the mind, it follows that any scientific study of art will be psychology. It may be other things as well, but psychology it will always be [1946, p. 128].

This essay is formally arranged around the major psychological orientations toward art. Psychologies of art—scientific and humanistic—are difficult to disentangle from psychologies of the artist and of the audience. For this reason, I have not attempted to separate art, artist, and audience in discussing different psychological traditions in art. In the first two sections, I introduce, discuss, and evaluate the humanistic and scientific approaches to psychological theories and data about art, artist, and audience. In each of these main stopping points in the psychology of art we discover a developmental dimension: development of the artist and development of the audience. In the third section of the essay, I review progress in the developmental psychology of art. In the fourth section, I discuss the historical development of Western art from a psychological vantage; and I raise the possibility of a psychologically universal aesthetic. The essay concludes with a discussion of future productive directions between psychology and art.

In this essay I am concerned with psychological viewpoints and do not broach philosophical, sociological, anthropological, or other related orientations to art. Art is limitless in conception and scope, and no one could argue that the political statement of Goya’s 2 May and 3 May 1808, the social compassion of Orozco’s Slave, or the impact of the call of an anonymous Chinese poster are any less psychological than the pregnant moment captured by Vermeer in The Love-Letter, the intense gloom and anguish of Munch’s Jealousy, or the pure and direct formalism in any Mondrian Composition. The word “art” itself invokes very different images and ideas in different individuals. This being the case, it is necessary to place limits on the conception and scope of our endeavor here, and this essay is therefore circumscribed to a psychological introduction to humanism, science, and development in the visual fine arts of the West—especially to painting—though the psychological principles discussed presumably extend to sculpture, architecture, photography, cinema, and theater.

THE HUMANISTIC TRADITION OF ART, ARTIST, AND AUDIENCE

The humanistic tradition in the psychology of art has tended to focus on the motivation to create art and on the meaning of themes in art, and has attended, albeit to a lesser degree, to reciprocal psychological responses of the audience to those motivations and themes. In this perspective art is an outlet for the artist and a conduit for the audience. Psychologists in the humanistic tradition have been especially attracted to the interrelated problems of creativity and artistic personality.

The question of whether artistic personality is special has classical roots. Plato proclaimed an Idealist view—the artist as divinely inspired; Aristotle proclaimed a Realist view—the artist as acute observer and interpreter of nature. However different, artistic personality has nearly always been characterized by an “otherness” from personality styles in the general population. Wittkower and Wittkower (1963) brought historical and sociological analysis to bear on this question and concluded that, from classical times until the present, three separate interpretations of eccentricity of artistic temperament have been entertained: “first, Plato’s mania, the sacred madness of enthusiasm and inspiration; secondly, insanity or mental disorders of various kinds; and thirdly, a rather vague reference to eccentric behavior [p. 101].” Hard data on the question of whether the artistic personality deviates significantly from the normal range, though sparse, suggest that it does not. Nonetheless, the “otherness” of artists has been a conception widely subscribed to by art historians, by psychologists, and by the lay public alike. This view reached ascendency with the dominance of emotion over intellect and reason in nineteenth-century Romanticism. The mainstream movement in art during this period popularly presented as subject matter basic feelings and emotional situations of life (Goldwater, 1967). The art of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944), which itself sometimes bordered on neurotic or hysterical, is characteristic of this time (Figure 2). Out of this Weltanschauung the most influential psychological movement in art, psychoanalytic theory, was introduced.

Freud was the modern fountainhead of the humanistic approach, and, like most of his opinions, Freud’s insights into art and the artistic temperament derived from self-analysis and from his studies and interpretations of abnormal character. Freud, it so happens, was also an art connoisseur and avid collector (Spector, 1972).

In spite of the thoroughgoing impact that Freud’s theory has had in the cultural domain—Lionel Trilling once observed that Freud “ultimately did more for our understanding of art than any other writer since Aristotle [1947/1953, p. 160]”—Freud’s original essays in the fine arts were infrequent, severely limited, and highly tentative. Freud seems to have used art more to explore the breadth of his brainchild psychoanalysis and less to provide exegesis of specific works of art. In one major effort Freud psychoanalyzed Leonardo to examine the influence of childhood experiences on mature personality, and in a second Freud analyzed Michelangelo’s Moses to show the intent of the unconscious in the para-praxes of the everyday life of an artist.

Freud observed that art works exerted an especially “powerful effect” on him, and he wondered why. He eventually arrive...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Series Prologue

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Psychology and Art

- 2. Psychology and Linguistics

- 3. Psychology and Literature: An Empirical Perspective

- 4. Psychology and Music

- 5. Psychology and Philosophy

- 6. Psychology and Religion

- Biographical Notes

- Author Index

- Subject Index