![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to medical law and ethics

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• gain a basic understanding of the nature of medical law and ethics;

• demonstrate an understanding of where to locate the law;

• appreciate the importance of reading primary sources.

INTRODUCTION

Medical law and ethics is an area of law which is rarely absent from the media and often appears part of our everyday lives in a way that few other areas of law do. We often hear and read about debates concerning assisted suicide and developments in assisted reproduction that are frequently captured by the tabloid press in a way that does them little justice. When you read this book it is hoped that you will be motivated to read further. By all means, read the current media reports in respected broadsheets such as The Times and The Guardian newspapers, but do also attempt to gain some academic depth by looking for relevant articles in academic journals such as the Medical Law Review and the Journal of Medical Ethics to name just two. A true depth of understanding can only really be achieved by reading the primary sources – it is therefore imperative to read the key cases fully. Getting into good habits early is always very advantageous! A similar sentiment applies to the statute law – the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 is surprisingly readable and accessing the original source and reading the relevant sections will give you a far greater understanding of the subject area. Medical ethics or bioethics easily engages one’s emotions and it is very possible that you may have already formed your own ideas on subjects such as abortion, assisted conception or end of life issues. It is important, however, to engage with other arguments and academic opinions and then use these arguments to either challenge or reinforce your own opinions.

There is occasionally confusion between the terms ‘medical ethics’ and ‘bioethics’ and it is useful to be able to distinguish between the two. Medical ethics describes a more traditional dilemma between the doctor and the patient. For example, Tom visits his GP who advises him that he is HIV+. Should the GP breach the fundamental rule of confidentiality between doctor and patient and inform Tom’s wife that he is HIV+ in case her health is also put at risk?

In contrast, bioethics is a more modern term that reflects modern-day ethical dilemmas in the field of medicine. The word bioethics comes from the Greek word bios meaning life and ethos behaviour. Modern medical advances in technology mean that the ethical dilemmas have become more complex and some decisions can affect society. For example, Ali wants to sell his kidney in order to use the money to support his family. Should he be permitted to? Other issues might include the circumstances in which it is ethically permissible to switch off a patient’s life support machine. More topical questions also surround whether assisted suicide should be legalised.

This book will provide the reader with an introduction to some of these areas and the ethical dilemmas will be addressed in the chapters that follow. Some of these issues often raise passionate responses such as ‘abortion can never be ethically acceptable’ and ‘assisted suicide can never be justified on moral grounds’; however, the reader should ensure that whatever opinion is held, the opinion can be justified by reference to an ethical theory and after thorough investigation.

The book is designed to help the reader with an introduction into the various areas of medical law. We begin by exploring ethical theories in order to gain an understanding of the way in which ethical decisions are made. We then embark upon a number of chapters outlining the law. We begin with a chapter on confidentiality. Why is this so important in a doctor– patient relationship and can this ever be breached? We then turn to resource allocation. NHS funds are limited; can every patient expect funding for every treatment they would like? From here we turn to more ‘black letter’ areas of the law and begin with medical negligence and a discussion of the duty of care owed to patients, and look at what happens when that duty is breached. The following two chapters explain the fascinating area of the law of consent and outline the move from paternalism to autonomy where the competent patient’s decisions regarding their medical treatment are concerned. How are incompetent patients treated? From here we move to mental health, a complex area of the law that is stripped back to basics here but which hopefully will encourage the reader to read more on this valuable topic. We then seamlessly move from law to ethics in what can best be described as ‘from birth to death’. We begin with assisted conception by considering what is meant by the term ‘assisted conception’ and the difficulties that can arise, before turning to surrogacy. Next, we encounter abortion law, a highly controversial topic in which we examine both the law and the ethics before moving on to the topical and important issue of organ donation. Our last two chapters deal with end of life issues, beginning with probably the most controversial topic of this decade, the law and ethics of assisted suicide and euthanasia. Finally, we turn to the question of withdrawing and withholding medical treatment from an incompetent patient, another complex legal and ethical issue. It is hoped that this book fulfils its learning objectives in introducing the reader to medical law and ethics.

![]()

Chapter 2

Introduction to ethical theories

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• understand the relevance of ethical theories within bioethics;

• appreciate different ethical theories;

• demonstrate an ability to recognise ethical dilemmas and apply ethical theories in an attempt to solve them.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will introduce the reader to the main ethical theories that govern bioethical dilemmas. It is important not to concern oneself with which particular ethical theory might apply in a specific bioethical dilemma but to appreciate that the theories you will read below are used interchangeably and seamlessly to resolve complex dilemmas. Towards the end of the chapter, you will encounter theories that are less common but they are included in order to give the reader a more complete picture.

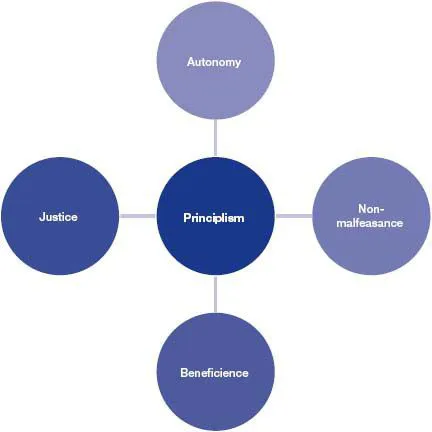

PRINCIPLISM

Principlism is based upon four fundamental principles and represents the most influential set of guidelines to apply to bioethical dilemmas. The four principles are shown in the diagram on page 4.

Autonomy

For some considerable time the courts have recognised the importance of patient autonomy although initially more readily in the USA than the UK. The fundamental nature of patient autonomy was recognised as long ago as 1914 when Cardozo J in Schloendorff v New York Hospital stated that ‘every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent, commits an assault’. Today autonomy remains one of the most important and fundamental guiding principles in the care of patients. Beauchamp and Childress define autonomy as ‘self rule that is free from both controlling interference by others and from limitations, such as inadequate understanding that prevent meaningful choice’ (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001, p. 58).

Figure 2.1

How is autonomy illustrated in practice? In Re C (Adult: Refusal of Medical Treatment), a case we will look at in further detail in Chapter 6, C, a paranoid schizophrenic, was considered to have sufficient capacity to refuse medical treatment to remove his gangrenous foot. Even though his decision was contrary to medical advice, he had the autonomy to be able to make his own decision. As patients we have the autonomy to decide whether to accept or refuse medical treatment, the only prerequisite being that the person is of full age and is competent to make decisions. Patients are able to refuse medical treatment even if the patient will die as a direct result of that refusal.

Seminal cases have highlighted the importance of patient autonomy. For example, in Airedale NHS Trust v Bland, Lord Mustill opined ‘If the patient is capable of making a decision on whether to permit treatment … his choice must be obeyed even if on any objective view it is contrary to his best interests.’ In a similar vein, Lord Goff explained that the

principle of self-determination requires that respect must be given to the wishes of the patient, so that if an adult patient of sound mind refuses, however unreasonably, to consent to treatment or care by which his life would or might be prolonged, the doctors responsible for his care must give effect to his wishes, even though they do not consider it to be in his best interests to do so.

On-the-spot question

? How important do you consider the principle of autonomy where medical treatment is concerned?

Non-malfeasance

The principle primum non nocere, meaning ‘above all do no harm’, is the foundation stone of medical treatment and non-malfeasance imposes a duty upon the medical professional not to harm others.

KEY CASE ANALYSIS: McFall v Shrimp 10 Pa D & C 3d 90 [1978]

In this American case, McFall, who was seriously ill, needed a bone marrow transplant from his cousin, Shrimp. Although Shrimp had initially agreed, he withdrew his consent. McFall took Shrimp to court for an order forcing him to give bone marrow, thereby foregoing his autonomy. The principle of not doing harm was in conflict. Where was the greater harm being caused? Would harm be caused to Shrimp, who could be compelled to donate bone marrow against his wishes, or would greater harm be caused to McFall if he were not to receive the bone marrow he needed? The court refused to order Shrimp to donate bone marrow against his wishes and McFall died shortly afterwards. The case, although not binding on any jurisdiction in the UK, underlines some important principles.

On-the-spot question

? Do you agree with the court’s judgment? It represents a difficult balancing act. Should Shrimp have had bone marrow forcibly extracted? Think of why this would not be the correct course of action even though it would save McFall’s life.

Beneficence

Beneficence imposes a positive duty to act in the patient’s best interests. Beneficence implies an obligation to do ‘good’ for the patient but sometimes the boundaries of what is ‘good’ for the patient can be blurred. For example, if a Jehovah’s Witness refuses a blood transfusion, preferring to die than to act against his faith, he expresses an autonomous decision, but if he were to be saved would that be doing ‘good’ and acting in his best interests? A different issue arises when a doctor cannot treat a patient by prescribing lifesaving or life enhancing drugs due to allocation of resources and problems of ‘postcode lottery’ (see Chapter 4). In these circumstances, the doctor cannot act in a beneficent manner, the patient’s autonomy is not respected and justice is not served.

A more complex and unique situation arose in the case of Re A (Conjoined Twins) [2001] a case we explore further in Chapter 7. The conjoined twins were to be separated but where was the greater harm caused? In separating the twins, the weaker and dependent twin would die but separation would give the stronger twin the chance of a normal life. If they were not separated, they wou...