- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women in Nazi Germany

About this book

From images of jubilant mothers offering the Nazi salute, to Eva Braun and Magda Goebbels, women in Hitler's Germany and their role as supporters and guarantors of the Third Reich continue to exert a particular fascination. This account moves away from the stereotypes to provide a more complete picture of how they experienced Nazism in peacetime and at war. What was the status and role of women in pre-Nazi Germany and how did different groups of women respond to the Nazi project in practice? Jill Stephenson looks at the social, cultural and economic organisation of women's lives under Nazism, and assesses opposing claims that German women were either victims or villains of National Socialism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION

1

German women and National Socialism

Introduction

The explosion of interest in the history of women and gender, triggered in the 1960s, has produced theories about how women’s status and opportunities have been determined in recent centuries. The way in which men have accumulated and exercised political, economic and social power, in Judæo-Christian society in particular, has been called ‘patriarchy’. In patriarchal society, women are subordinate to men in virtually all areas of both public and private life. This has not merely been an informal arrangement; rather, it has been entrenched in a wide variety of societies by legislation and custom. Religious institutions, including the Christian churches with their male clergy, have sanctified it and contributed to a social system in which the dominance of men and the subordination of women have been enforced by the discipline of a community’s acceptance or disapproval of individuals’ conduct. There has been no doubt about who has held power, in society and in individual households: men’s greater physical strength has been the implicit, and at times the explicit, guarantee of their authority.

Under this cultural code, the normative division of labour between men and women in urban, industrial society has, until recently, been that of men acting as breadwinners and women as homemakers. Where a woman worked in a family concern like a small farm or trade, as in pre-industrial society, she remained responsible for the conduct of the household and for child-rearing. She would normally be excluded from associational, public or political life, arenas reserved for men, although she might belong to gender-segregated groups, mostly those associated with her church. Some historians have viewed these ‘separate spheres’ – the ‘public’ and the ‘private’ spheres – as arenas in which each gender could realize its potential. Where women have largely been confined to the ‘private sphere’ of the home, and excluded from the ‘public sphere’ of employment and political and public affairs, they are, some believe, able to construct distinctive centres of power and influence, especially in specifically women’s social and organizational life. This has empowered them, as agents responsible for their own destiny, rather than waiting passively as subjects or victims of men wielding power.

These ideas have particular relevance for the study of women in Nazi Germany. Questions have been asked about whether women can be considered accomplices of the Nazis if they supported the NSDAP as voters and/or participated in Nazi women’s organizations. Again, economic recovery, with the expansion of the armed forces and heavy industry in the 1930s, followed by war from 1939 to 1945, brought more women into multifarious activities outside the home – into the public sphere. This has provoked claims that the Nazi regime – albeit unintentionally – provided more rather than fewer opportunities for women beyond the private sphere of the home. Further, it has been suggested that, by insisting on gender-segregated organizational life, the Nazis afforded women ‘space’ to empower themselves and to liberate themselves from traditional constraints. Conversely, it has been argued that women willingly retreated into their traditional domestic space, so that German wives and mothers, by providing a comfortable home for men committing racist atrocities, were themselves guilty of colluding in heinous crimes. By contrast, some have argued that women were particularly and peculiarly victims of the National Socialist system.

These questions of entrenched male dominance, or patriarchy, separate spheres, female agency, and whether women were ‘perpetrators or victims’ in the Third Reich remain, in varying degrees, controversial. They should be tested against an empirical reconstruction of the past, particularly because during and since the 1930s myths and misinformation have distorted representations of women’s position in Nazi Germany. Although some historians have exploded these myths, they persist as the common currency of even educated opinion about the Third Reich, perhaps because the distortion is more sensational than prosaic reality. Suffice it to say that, while National Socialism was an evil creed that brought misery and death to millions of both sexes, we should not assume that in the Third Reich all women were reduced to the status of serfs. Some women – like some men – were treated with appalling and often calculated cruelty, but the majority were not. Women as a gender were discriminated against in various ways in Nazi Germany, but often this reflected the experience of women in other industrially-advanced, patriarchal societies, where lower wages, a marriage bar and extreme underrepresentation in the higher reaches of management, the professions and public life obtained. Where women’s experience under Nazism was unusual, indeed unique, was in the realm of reproduction, where woman’s function as mother of the species made her distinctively the focus of attention, pressure and, in some cases, both physical and mental cruelty.

This justifies treating ‘women in Nazi Germany’ as a category, even when ‘women’s history’ is being superseded by ‘gender history’. Further, we should confront Eve Rosenhaft’s astute challenge that ‘women are invisible unless we are looking straight at them’ (1992: 160, her emphasis). This book, then, looks straight at women, reviewing the roles, functions and room for manoeuvre of women in the Third Reich against how these were conceived and controlled by the Nazi leadership. Nevertheless, women’s experience must be assessed in comparison with men’s. For example, if ‘women’ had no political power in Nazi Germany, neither did ‘men’, in a one-party dictatorship. Even if the only people wielding political power were men, the vast majority of men were politically impotent. Further, given the way in which gender-segregated organizations developed, some women were able to wield within them – and within only them – authority of a kind inaccessible to most men. Yet while there is merit in assessing women’s roles and opportunities separately, ‘women’ should be integrated into history, particularly social history, and should not be ‘ghettoized’ as they have been, either with an obligatory separate chapter or chapters on ‘women’ in anthologies or else – even in books by some of the best historians – confined to a couple of paragraphs or pages. Provided that this does not result in renewed invisibility for women in history, it should be the aim.

The Nazis’ inheritance

Like any aspect of the past, ‘women in Nazi Germany’ should be viewed within its historical context. This does not mean minimizing the extent and wickedness of Nazi atrocities, or ‘relativizing’ National Socialism by comparing it with other political systems. Simply, whatever programmatic ideas Nazi leaders had, they did not start from scratch. Firstly, they were partly constrained by the German, and European, socio-economic context. The evolution of German society, from being predominantly agrarian c. 1870 to being predominantly urban in the 1920s, had profound effects on women’s roles and on both sexes’ perceptions of them. Nevertheless, traditional attitudes remained entrenched in most sectors of society, and in the views of the highly-influential Christian churches in particular. In the 1933 census, 95 percent of Germans claimed membership of either the Evangelical (Protestant) or Roman Catholic churches – in a ratio of two to one (Statistisches Jahrbuch, 1935: 14) – which favoured a domestic, maternal role for women and deplored both increasing resort to contraception to limit family size and the employment of married women outside the home.

Further, Germany did not exist in a vacuum: developments in other countries coloured attitudes and influenced Germans. The example of ‘Bolshevism’ in the USSR, bringing radical changes in women’s status after the October Revolution in 1917, was for some Germans an inspiration but for most an outrage, while the permeation of Germany, like other advanced countries, by American cultural influences in cinema and popular music was, similarly, embraced by some and deplored by others. Traditional opinion, dominant within the urban middle classes and among rural dwellers, found a scapegoat for Germany’s ills in the quixotic amalgam of Bolshevik radicalism and licence with American consumerism. The removal of traditional restraints that both symbolized was epitomized by the image of the ‘new woman’, the ‘cigarette-smoking, motorbike-riding, silk-stockinged or tennis-skirted young women out on the streets, in bars or on the sports field’ (Harvey, 1997: 281).

In Germany, as in other industrially-advanced countries, fundamental changes had affected women’s lives and expectations. In particular, a dramatic reduction in rates of perinatal maternal mortality – death of mothers in childbirth – from c. 1900 decisively altered the balance of life expectancy: thus, in the twentieth century women could, on average, expect to live longer than men. Further, medical advances meant fewer women spending years as invalids after some mishap in childbirth. Significantly, also, a consistent decline in infant mortality meant that achieving a desired family size was increasingly predictable, especially with the increasing availability of fairly reliable contraceptives, along with safer abortion techniques. These developments had enormous implications for women’s health and aspirations. The possibility of achieving control over their fertility – although for many this was only imperfectly realized – enabled many more women to develop ambitions in the public sphere beyond the realm of home and family.

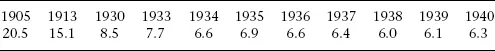

Table 1.1 Infant mortality, 1905, 1913, 1930 and 1933–40, per 100 live births

(Statistisches Jahrbuch des Deutschen Reiches: 1914: 33; 1934: 48; 1938: 66; 1941/42: 21*)

The growth of large-scale industry enabled women, like men, to find regular paid work outside the home, with physical strength no longer vital in many mechanized occupations. Further, the invention of the telephone and typewriter in the later nineteenth century created employment opportunities for women – who, allegedly, not only had nimble fingers well-suited to work with a keyboard or switchboard, but also were mentally and psychologically fitted for repetitive tasks. If it was obvious that women and men were physiologically different, in both reproductive functions and physical strength, it seemed to many equally clear that women were psychologically and intellectually different from – and, generally, inferior to – men. Nevertheless, although some university professors claimed that academic study ‘is not suitable for the feminine nature’ because women were ‘always more intuitive and irrational’, women students’ numbers increased steadily during and after the First World War, while a few women entered professions for which a university degree was required (Stephenson, 1975a: 42–43). Yet the Civil Code of 1900 gave fathers sole authority in determining the nature and duration of their children’s education; therefore even girls showing academic promise might be denied an academic education because it would be ‘wasted’ when they married. The Weimar Constitution’s pledge of equal opportunity for the sexes in education did not override that.

While there are spinsters and widows in any society, adult single women were unusually evident in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, after the wartime slaughter of around two million men, of whom some 85 percent were aged between 18 and 34, and almost 70 percent were unmarried (Bessel, 1993: 6–10). This ‘surplus of women’ (Daniel, 1997: 288), as it was inelegantly termed, was therefore prominent among women in their thirties, forties and fifties during the 1930s. Many had never married, but some were young widows of the slain. Further, after 1918 the incidence of divorce was more than double its prewar rate, and it continued rising into the 1930s (Stephenson, 1975: 38, 52). Women who remained or became single during and after the war had to support themselves and perhaps also dependants, and therefore required paid employment, whether they were middle-class or working-class. Only in wealthy homes which escaped impoverishment by the inflation crisis of the early 1920s and the depression from 1929 could an unmarried woman enjoy a life of leisure. The spectacle of substantial numbers of independent single women both at work and pursuing an active social life created anxiety in conservative and church circles, and convinced many that the institution of the family was in crisis, particularly as ‘the family’ now had fewer children than in the prewar years.

Yet the traditional ideal persisted: a young woman’s education would prepare and socialize her for her presumed future as a wife and mother; she would take paid work until she married – as she undoubtedly hoped to, with ‘old maid’ still a pejorative term (Bergen, 1996: 122) – when she would retire to devote herself to unwaged work for husband, home and family. This was the expectation not merely in the middle classes but also in better-off urban working-class circles. In these families, daughters and sons were nurtured distinctively differently, to accord with the differing futures envisaged for them. Nevertheless, many working-class wives worked from home – perhaps as seamstresses – while a minority would, through poverty, need to work outside the home, possibly in a factory. In families with a small business, like a shop or an artisanal trade, the women – wife, daughters and perhaps sisters – were expected to assist as and when the male proprietor required, without receiving a formal wage. Similarly, in farming families, women worked on the farm. Women working in a family business were considered appendages to their male head of household, and were classed as ‘assisting family members’ in censuses. In 1925, over four million women, in a total female employed population of 11.5 million, met this description (Winkler, 1977: 195).

Catastrophic depression from 1929 acutely affected women’s socioeconomic position. With jobs increasingly scarce, there was resentment when women – and especially married women – were employed; they were, allegedly, stealing men’s jobs. This was only partly plausible: many women worked in traditionally gender-specific occupations like nursing, childcare, sewing. Cold facts, however, did not appease those who believed that an ‘emancipation of women’ had occurred in the 1920s, to the detriment of men and at the expense of population growth. If this had some substance, the sadder truth was that employers might dismiss male employees in order to employ women, whose wage rates were lower.

The depression sharpened antagonisms throughout German society, especially between those campaigning for enhanced rights and opportunities for women and those determined to prevent further erosion of traditional gender norms and relations. The economic crisis both disposed more Germans to suspect feminists and put feminists of various kinds on the defensive. The long-standing divisions in their ranks would make it easy for the National Socialists, in government, to suppress their organizations and victimize their leaders, most of whom were middle-aged or elderly single women who met neither society’s nor the NSDAP’s ideal standard. Those who had always suspected feminists seemed, in the depression, vindicated in their view that the place of a married woman, and, especially, a mother, was in the home.

The image of a married woman’s life as that of full-time housewife and mother reflected not only entrenched tradition but also the realities of early twentieth-century life in societies where the traditional division of labour obtained. Certainly, industry mass-produced various consumer goods, but not the ‘consumer durables’ that revolutionized housekeeping later in the century. Thus running a home in an advanced Europe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of tables

- Author’s acknowledgements

- Publisher’s acknowledgements

- Chronology

- Maps

- PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

- PART TWO: WOMEN IN THE RACIAL STATE

- PART THREE: ASSESSMENT

- PART FOUR: DOCUMENTS

- Glossary

- Who’s who

- References

- Guide to further reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Women in Nazi Germany by Jill Stephenson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.