![]()

1.1 Introduction

This should be easy – at least in theory. Fossil fuels are finite. So too is the atmosphere. Sooner or later, our energy systems have to change.

Economic theory predicts that the price of a limited resource will rise as it is depleted, until it reaches a point at which alternative technologies compete and take over. Economics recommends that if there is an ‘external’ impact, like health or environmental damage associated with burning coal, then governments should tax emissions to reflect the cost of damage caused or impose a cap on emissions to the same effect.

In fact of course it is not easy – no one seriously claimed otherwise. Fossil fuels have been at the heart of economic development. Coal-based steam powered the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth and centuries, and electricity and the internal combustion engine between them did much to shape the twentieth. Energy provides the heat to warm our homes and to produce and transform industrial materials, the electricity that lights our buildings and powers our appliances, communications and entertainment systems, fuel and fertilisers for the agricultural ‘green revolution’, and the motive power to transport ourselves and our goods. The benefits have been enormous.

The link between energy and development has been clear. The economic boom of industrialised (mostly) nations after the Second World War – roughly the third quarter of the last century – was accompanied by a trebling of global energy demand.1 That came to an abrupt halt with the oil shocks of the 1970s. The resumed and more global economic growth since the late 1980s – often attributed to economic liberalisation in the ‘developing countries’ – followed the collapse of oil prices in the mid-1980s and was again accompanied by surging energy demand, which has doubled again over the past quarter century.

Yet all is far from well. Over a third of the global population – 2.5 billion people – still live in grinding poverty and depend on traditional wood and other biomass for cooking and heating; half of them remain unconnected to electricity.2 The growth potential – and need – is huge, but they have missed out on the interlude of cheap fossil fuels. The gyrations of global oil prices since the late 1990s and steep increases since 2005 have caused real hardship and been implicated in further economic recessions.

Along with relentless growth in global fossil fuel use has come a series of environmental problems, of growing scale and reach. At first, these impacts concerned contaminant pollutants, like smog and sulphur, or the side-effects of extraction. Dealing with these formed major policy battlegrounds in the twentieth century, but with hindsight proved relatively easy to deal with. CO2, however is not a contaminant but the fundamental product of burning fossil fuels. With concentrations already at levels not seen for millions of years, it continues to accumulate relentlessly in the atmosphere.

This book is about the interplay of theory, evidence and policy implications applied to these challenges. Despite the mind-boggling scale of the issues, the fact remains that the traditional economic theories of such problems are quite simple and date back more than three-quarters of a century.3 They focus particularly on the role of prices and the trade-off between costs and benefits. We can now also match these theories against the evidence of practical experience of these systems and responses: almost forty years of efforts to tackle oil dependence since the 1970s, and two decades of policies to tackle CO2 emissions.

The experience is sobering. It points to the fact that the systems involved are far more complex than any single theory assumes. Industrialised countries have struggled to reduce CO2 emissions and most of the emerging economies – the majority of the world’s populations – are still following in the footsteps of the fossil-intensive Western model of development. A view is emerging that the problems are just too big to solve. Vast investments are flowing into new frontier developments in harder-to-reach fossil fuels, and domestic and international discussions on climate change talk increasingly about how to cope with the climate impacts implied by the failure to control emissions – and who should pay for it.

The core argument of this book is that the dominant theories simply do not match the scale of the challenge – they have been extended out of their depth. Different approaches point to different bits of the problem – different ‘parts of the elephant’ – without an overall picture. This in turn has made it far harder to map coherent responses and gain the political consensus required to implement them. Behind the failure of policies to adequately get to grips with the problems lies a failure of theory to reflect crucial realities – and hence our apparent inability to get on a sustainable course.

This book is addressed to governments and researchers, and to the wider public interested in understanding more deeply the real problems and opportunities. It explores the gap between classical theory and the accumulated evidence and what this says about the options and policy implications. The evidence comes both from extensive research in modern branches of economics and other disciplines and the practical experience of policies. It is about how these systems behave, what research has concluded, what policy-makers have tried and what the combined results imply.

Since this book stresses evidence – empirics – as the foundation for useful theory, the rest of this chapter presents some basic evidence about the nature of energy and related environmental systems, particularly their economic dimensions. The next chapter then sets out a new framework for thinking about the issues – one which emphasises that different theories fit different scales, and that the key need is to understand their assumptions, boundaries and relationships: how in reality they may complement rather than compete as explanations and guides. This then defines the structure for the rest of book, which examines the key ideas, data and experience at each of these levels. The final chapter then draws all this together to offer a wider and more integrated understanding of the economics of energy transformation and the implications for practical policy.

1.2 The physical challenges – energy, resources and climate

Energy trends

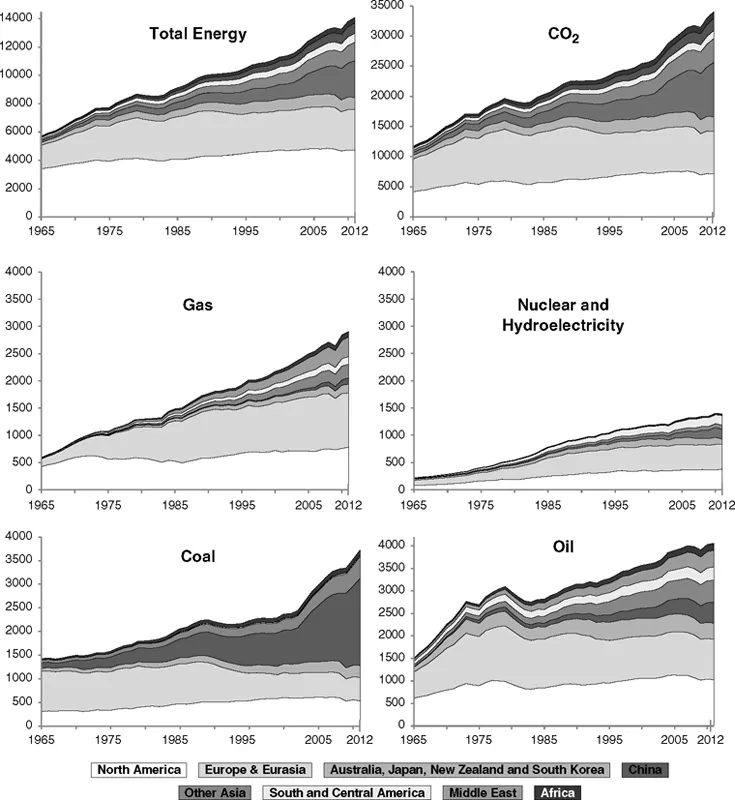

Broken down by fuel and region, Figure 1.1 illustrates the extraordinary increase in global energy consumption over the past 45 years – at first dominated by the industrialised countries, giving way more recently to growth particularly in Asia. Along with the march of oil consumption, most striking is the recent explosive growth of coal use there, along with global rising use of natural gas. After an initial spurt of nuclear power, non-fossil energy sources overall only kept pace over the past quarter century, at just under 15 per cent of the global total; continued growth in hydro and more recently wind energy has compensated for a slow-down in nuclear generation. The overall trend in both energy and CO2 emissions has been relentless and the most severe global recession in living memory – 2009 – dented it for just one year.

Figure 1.1 Energy trends by region and fuel, 1965–2012

Note: The charts show for each fuel the total energy consumption by region, in million tonnes of oil-equivalent.

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2013).

Growing energy consumption is of course a mix of good and bad news. It reflects rising living standards for billions of people – including connection to electricity and the use of fossil fuels displacing potentially more damaging use of local forest and other biomass burning for heat and cooking. Since the 1980s roughly a billion people have been connected per decade.

In fact, the most important single energy contribution is not shown in Figure 1.1, namely energy efficiency. As examined more closely in Chapter 4, in the decades since the oil shock economic growth exceeded that of energy and emissions in almost all regions – reducing their energy (and carbon) intensity, defined as the ratio of energy to GDP. The idea that GDP and energy/emissions are locked together is a myth, but the improvement in most regions has been outstripped by the rate of GDP growth. The decline in global energy intensity has also slowed in the past decade, though the pattern is quite varied between countries, and a few leading countries have since the mid-1970s roughly doubled their GDP without increasing their energy demand (Chapter 5, note 51).

In addition, many countries showed evidence of an ‘energy ladder’ in their mix of sources, with a shift towards electricity and lower carbon fuels over time (though the boom in Asian, particularly Chinese, coal has been a crucial exception).4 Yet globally, all this has been at a far slower pace than GDP growth itself. At a global level, nothing in these data suggests that the pressures on fossil fuels will lessen – quite the contrary – and there is little sign of a global turnaround.

There are two basic problems with this trend: what goes in, and what comes out.

What goes in: the fossil fuel roller coaster

If the modern world is built on fossil fuels, then its most important single component – the global oil market – has proved disturbingly unstable. Cheap oil, boosted by mid-century discoveries of massive ‘supergiant’ fields mainly in the Middle East, helped to fuel a quarter century of rapid economic expansion after the Second World War.

That period came to an abrupt end with oil shocks in the 1970s (Figure 1.2). As the countries that sat on the bulk of global oil reserves asserted their control of it, against an increasingly unstable political backdrop in 1973, the global oil price more than doubled. Economic growth rates plummeted as inflation rose and huge amounts of finance were wrenched away from the industrialised world, slowly returning as recycled petrodollars. Six years later, with the Iran–Iraq war, oil exporters tightened the throttle and prices doubled again, precipitating another global economic downturn.

Global oil demand at the time was dominated by the industrialised countries. Stung by the high prices and loss of control, they turned to other fuels for electricity generation, and consumers moved from oil heaters to coal or gas and bought more efficient cars.5 The rich country governments also invested hugely in new frontiers of oil development and established strategic stockpiles, while the US entrenched its military presence in the Middle East. The Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) had to cut back supply in a bid to maintain the price – which finally crashed in 1986 when Saudi Arabia refused to continue ‘carrying the can’ for cutbacks. After a turbulent 15 ...