![]()

PART I

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS AND DEFORESTATION

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The concern about the present speed of global tropical deforestation and tropical forest losses that have already occurred, especially during the last decades, is so widespread that the issue is now commonly perceived as a major international one. Part of the concern explicitly highlights the potential damage for people, both current and future generations; another area of concern merely focuses on the vulnerability of the ecosystems. Often, however, these two major concerns about tropical deforestation are seen as going hand in hand.

One has to admit that tropical deforestation may have economic benefits for various groups involved, at least in the short term, but it can also have serious economic repercussions. One of the main economic benefits from tropical deforestation is the increased land area that becomes available for economic use, such as for shifting cultivation, plantation or agroforestry or cattle ranching. If the deforestation is due to logging, another benefit is the availability of timber.

The costs, however, are first of all related to lost opportunities, through the production of non-timber products (e.g. through the traditional hunting-gathering tribes, but also through a more 'commercial' approach), or through recreation (ecotourism). After all tropical forests have built up the world’s largest biomass per hectare and contain a great diversity of plant and animal species. In addition, deforestation can have an adverse impact on the fertility of the area through soil erosion and runoffs. The costs in downstream areas can be sizeable indeed, because forests have a twofold buffer activity; first, the tree canopy intercepts the rain, and second, the humus and the roots absorb and recycle water. Loss of these functions results in rivers coming from deforested lands flooding excessively after a downpour, but quickly running dry thereafter (e.g. the Himalaya slopes versus the rivers in the Ganges plain and Bangladesh).

Another negative factor in deforestation is that the local climate can be adversely affected, often in an unquantifiable way. Since evaporation greatly increases the humidity in the vicinity of a forest, the taller the forest the more water it puts into circulation. This removes from a local climate the extremes of heat, cold and drought. If the supply of water vapour dwindles, the zones which suit certain crops soon shift and/or become narrower (especially in the large continental masses of Africa and Latin America).

A third cost factor is due to the loss of the world’s genetic materials, half of which are probably located in the tropical forests. Precisely because the economic losses that may be involved with the extinction of various plants and animals remain for the most part unknown, these losses are generally perceived as a matter of great concern. Moreover, tropical rainforests, once destroyed, are almost impossible to restore, for the tropical rainforest perpetuates itself in ‘cyclical regeneration’. Ecologically, therefore, it is a stable environment, with the maximum number of species possible under the circumstances: any external influence can only result in impoverishment. Ironically there is nothing to manage in such a system; the only way to preserve it is to protect it from interference of any kind.

Finally, the relationship between global tropical deforestation and the global climate issue, the greenhouse effect in particular, has become a major concern. Because tropical deforestation to a large extent takes place through slash-and-burn techniques, and because the CO2 content of the replacing biomass is less than that of the original vegetation, there is a net CO2 emission involved with the disappearing tropical forest. Although there is considerable variation in estimates on how this effects the overall CO2 emissions, roughly between 7–30 per cent (Mors, 1991, p. 81), it is in any case clear that this cost component of deforestation is serious indeed. It may involve not only the negative impact of climate alterations, such as shifts in the rainfall patterns, in moisture, or the mean air and/or sea temperature, but especially the exponential expansion of extreme weather conditions due to small shifts in mean values of climate variables.

![]()

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF TROPICAL RAINFORESTS

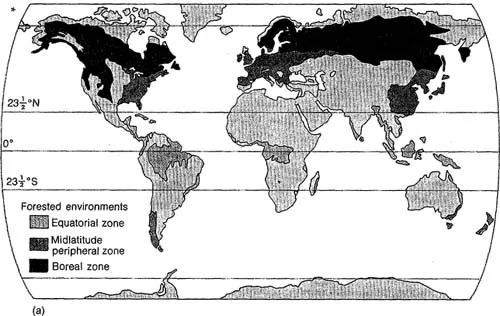

The total area of the globe where the conditions are fulfilled for tropical rainforests to survive can be estimated as some 1046 million hectares (Hagget, 1979); according to WRI (1990, Table 19.1, pp.292–3) the tropical forests currently account for 42 per cent of the world’s total forest area. The major share of this tropical forest area is situated around the equator, either in Latin America and the Pacific, or in Asia and Africa. The main countries where the conditions for closed forests of the permanently humid tropical regions are fulfilled are Brazil, Zaire and Indonesia, with a forest area of 34, 12 and 8 per cent respectively of the world total; the remainder is situated in some 40 other countries.

According to Jacobs (1988, pp.2–6) the following physical conditions have to be fulfilled to enable the natural development of a tropical rainforest:

• A relatively continuous tropical temperature, with a small amplitude both through the day and throughout the year. This condition generally holds for latitudes between 23 ° 30′ N and 23 ° 30′S, at least if the land is below 1000m altitude.

• At least 1800mm rainfall per annum, evenly distributed throughout the year.

These conditions have proven to be necessary but not always sufficient for the natural development of tropical forests.

It is obviously a matter of definition to assess the precise boundaries of the rainforests, especially if these forests gradually transit into non-evergreen forests. The practices that have led to deforestation have exacerbated the difficulties of defining the tropical forest area both in qualitative and quantitative terms. However, the main range of a tropical rainforest is well-known. Jacobs (1988, pp.3–4) distinguishes the following main regions:

1) The American rainforest region. On the South American continent three rainforest subregions can be distinguished:

– Amazonia, by far the largest and still mainly intact;

– a second region west of the Andes and north of the equator extending intermittently to Mexico. This region has already suffered badly;

– a third and smallest region consisting of a narrow strip along the Atlantic coast of Brazil between 14 ° and 21 ° S; only a few remnants of it still exist.

2) The Malaysian rainforest region or Southeast Asian region. This region coincides almost entirely with the former Malaysian Archipelago (the Papua New Guinea and Irian Jaya island included), to which the Malay Peninsula belongs botanically; the true rainforest is almost absent from continental Asia, except in Malaya, southern-most Thailand and Southwest Cambodia.

In this region two closely related nuclei can be distinguished. First, Borneo-Malaya-Sumatra and The Philippines, with outliers in the Andaman Islands, Sri Lanka and the poorer forests of Southwest India. Second, the Papua New Guinea and Irian Jaya island, including the less species-rich forests on the islands to its west and east, with an outlier along the eastern coast of tropical Australia, where some pockets of rainforest have survived. Forests in Malaya, Sumatra, Borneo and The Philippines have been heavily depleted in recent times: the Papua New Guinea and to a lesser extent the Irian Jaya forests thus far have remained largely intact.

3) The African rainforest region. This region consists of a number of subregions, all partly destroyed, both along the Atlantic coast between ca. 10 ° N and 5 o S, and in the Congo Basin stretching east to the mountains. In addition, some outlier pockets in East Africa may be regarded as more or less true rainforests.

Source: Hagget (1979)

Figure 1.1 Main environmental regions

ESTIMATES OF FOREST RESOURCES AND DEFORESTATION

The size of the tropical forest resources and the amount of deforestation obviously depend on how they are defined. Since there is no consensus about the correct definition of both concepts among the various experts and institutions involved, a definite assessment of the size of deforestation processes cannot be made, even if the registration techniques are perfect, which they are not.

The extreme points of view with respect to forest resources and deforestation can be traced down to different angles from which the tropical forests are viewed. On the one hand one distinguishes what could be labelled as the environmentalists’ point of view, according to which the tropical forest should be considered primarily as an unique ecosystem that should be preserved in all its biological diversity. On the other hand one can distinguish the forestry sector point of view. According to the latter, the tropical forest is recognized as being a vulnerable ecosystem, but should be valued equally on the basis of the economic value of its resources, e.g. through the exploitation of its timber or otherwise.

These different points of view, i.e. those of the ecologist vs the economist, pervade the whole debate on the modalities, size and scope of deforestation, and also on how best to deal with the issue through policy measures. The above caveat should also be borne in mind when reviewing the various definitions of deforestation, and even impact upon the forest resources estimates.

Box 1 Main peculiarities of the rainforest: a botanist’s point of view

(Jacobs, 1988, pp. 4–6)

1) They contain the largest number of species, of animals and plants, of any known ecosystem;

2) they occur generally on poor soils;

3) in comparison to other forests, their potential for utilization is greatest in terms of quality, but smallest in terms of quantity;

4) they cannot easily be cropped in quotas;

5) they contain huge capital assets in the form of timber which, unlike non-timber products, generally cannot easily be harvested without serious ecological damage;

6) they cannot be 'managed' without the loss of a large number of species;

7) they are unusually fragile, and, once damaged, do not recover, or recover too slowly for any human planning;

8) nearly all of...