As teachers, you know that students in today’s increasingly diverse classrooms differ in language, culture, experiences, background knowledge, talents, interests, and cognitive ability. This is especially true as the movement grows to include in general education classrooms students with special needs, who in the past have been placed in separate special education classrooms. Therefore, you will need to carefully consider how you can structure your classroom and adapt your curriculum and teaching to meet the needs of all your students. The purpose of this chapter is to describe inclusive education and its origins and to outline in broad strokes curricular, pedagogical, and collaborative approaches that have been associated with successful inclusive classrooms.

A Brief History of Special Education

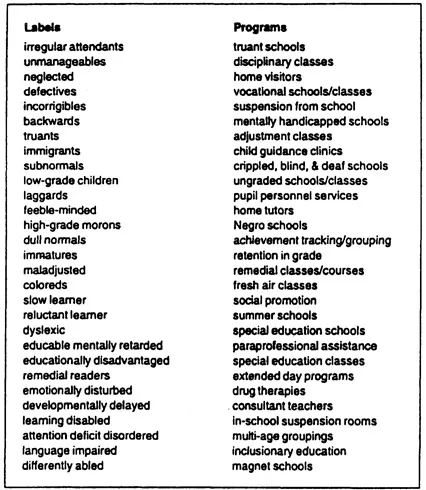

Throughout the 20th century, various labels have been applied to students who were considered “the hard-to-teach, the hard-to-reach, and the least privileged” (Allington, 1994, p. 97). Whether they have disabilities, are at-risk, are low achieving, have limited English proficiency, or are marginalized for some other reason, they have traditionally been placed in specialized programs that excluded them from the regular educational system. Examples of programs developed for students with disabilities and the ways those students have been labeled throughout this century are listed in Fig. 1.1.

FIG. 1.1. Labels and programs for marginalized students in American elementary schools, 1900-2000 (Ailing ton, 1994, p. 99; reprinted with the permission of Richard Ailing ton and the National Reading Conference.)

In response to federal legislation and court rulings, these labels and programs have changed over time and grown in number. The most important federal legislation affecting special education was the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, known as Public Law 94-142, renamed the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, (PL 101-476) in 1990). Originally passed by Congress in 1975, the purpose of IDEA was to provide equal educational opportunity and access to the public schools for students with disabilities. In addition to mandating that students with disabilities have access to a free, appropriate public education, IDEA also established the concept of the least restrictive environment (LRE). The intent of LRE is to educate students with disabilities along with their nondisabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate, and for special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of students with disabilities to occur “only when the nature of the severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aid and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily” (IDEA, 1990, p. 169). Although LRE has often been confused with mainstreaming, these terms should not be used interchangeably (Osborne & DiMattia, 1994). Whereas LRE refers to a range of possible placements, with a preference for general education settings, mainstreaming refers to the practice of placing students with disabilities in the general education classroom, which is only one of the options available in LRE. However, to many educators mainstreaming has become associated with cost-cutting measures in which students with disabilities are placed in general education classes without the necessary additional supports and services (see Hardman, Drew, & Egan, 1996).

Since IDEA went into effect in 1976, special education has grown enormously. In 1994/1995, for example, more than 5.2 million children (10% of all students enrolled in school) were receiving special education services (U.S. Department of Education, 1997). Tens of thousands of additional special educators have been hired, representing 13% of all teachers in the United States in 1990 (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1994). Not surprisingly, state-reported expenditures for special education have also grown enormously. For example, $18.6 billion was spent on special education and related services in 1989/1990 (Chaikind, Danielson, & Brauen, 1993).

As the number of students in special education has grown, so have the different kinds of specialized programs in segregated settings and the special education personnel to staff them (Allington, 1994). Critics of LRE (see Lipsky & Gartner, 1996; Taylor, 1988) have argued that, although LRE states a preference for the education of students with disabilities in regular education settings, it legitimates segregated, restrictive environments. Taylor (1988) argued that defining LRE operationally in terms of a continuum of educational placements, ranging from the most restrictive environment to the least, suggests that the most restrictive setting, such as an institution or special school, would be appropriate under some circumstances. Further, according to Taylor, the continuum of placements confuses the physical setting with intensity of services; that is, it assumes that the most restrictive and segregated placements offer the most intensive services, whereas the least restrictive and integrated settings provide the least intensive services. Yet, as critics note, intensive services can be provided in integrated settings, and some of the most segregated settings have provided the least effective services. Another criticism is that LRE is based on the readiness model, which assumes that people must acquire certain skills and thus “earn” the right to move to the least restrictive setting. However, critics argue that restrictive environments do not prepare people for more integrated settings. Yet another criticism is that the criteria for assigning labels and determining placements are ambiguous, vary widely, and are influenced by issues of race, class, and gender, as well as funding considerations.

The percentage of students who are classified as needing special education varies enormously from state to state. Based on an analysis of Department of Education data, U.S. News & World Report (Shapiro, Loeb, & Bowermaster, 1993) reported that 15% of students in Massachusetts were labeled as special needs students compared to only 7% in Hawaii and 8% in Georgia and Michigan. In Alabama, 28% of special education students were classified as mentally retarded, compared to 3% in Alaska. Furthermore, a disproportionate number of special education students were from minority groups. For example, African-American students were two to three times as likely as White students to be classified as mentally retarded; when White students were classified, they tended to be given the less stigmatizing label of “learning disabled” (LD). Wide discrepancies also occurred among states in their labeling of African-American students: Whereas five states (Alabama, Ohio, Arkansas, Indiana, and Georgia) labeled 36% to 47% of their African-American students in special education as mentally retarded, five other states classified less than 10% of such students as mentally retarded (Nevada, Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, and Alaska).

According to statistics from the Report of the American Association of University Women (AAUW, report 1992), far more boys than girls are referred to special education, although medical reports indicate that disabilities occur almost equally in boys and girls. Furthermore, girls who are identified as LD have lower IQs than boys labeled as LD, suggesting that boys are overreferred. Socioeconomic status (SES) also plays a role in referrals to special education, although it is a complicated one. Teachers who perceive themselves as ineffectual are far more likely to refer lower SES children with mild learning problems to special education than similar children from higher SES families (Podell & Soodak, 1993).

According to Allington (1994), classification has more to do with lack of early literacy experience than with innate ability: “The most direct route to being identified as at risk or handicapped in schools today is to arrive at school with few experiences with books, stories, or print and then exhibit any sort of difficulty with the standard literacy curriculum” (p. 95). Others argue that labels and segregated settings are designed to serve the needs of schools and society—not students—by attributing the problem of school failure to deficiencies in students, their parents, or their culture, rather than to inappropriate educational programs or practices (McDermott & Varenne, 1995; Skrtic, 1991). A related concern is that decisions regarding classification and placement are highly influenced by funding patterns rather than clinical evidence or objective judgments (Kliewer & Biklen, 1996).

Finally, there is growing evidence that separate education programs have not been beneficial for students with disabilities (see Allington, 1994; Lipsky & Gartner, 1996). A recent U.S. Department of Education report (1997) reveals that less than 50% of students with disabilities receive a regular diploma at graduation, and 38% drop out before graduation. Other national reports indicate that two thirds of persons with disabilities are unemployed, although the vast majority say they would like to be working; when they do obtain employment, it tends to be in part-time and low-status jobs; and more youth with disabilities are arrested than are nondisabled youth (Lipsky & Gartner, 1996).

As a result of criticisms of LRE and separate classes, there has been a renewed call to educate all students in the regular educational system. Referred to as inclusive education, this movement is currently a hotly debated topic among general and special educators and in the media. For example, some organizations, such as The Association of Persons with Severe Handicaps, have become strong advocates of inclusion, whereas other groups, such as The Council for Exceptional Children and the Learning Disabilities Association, support a continuum of educational placements (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1994). (For an overview of the debate among special and general educators, see the 1994/1995 and February 1996 issues of Educational Leadership.)

Inclusive Education

While focusing on individuals with disabilities, advocates of inclusion seek to change the philosophy and structure of schools so that all students, despite differences in language, culture, ethnicity, economic status, gender, and ability, can be educated with their peers in the regular classroom in their neighborhood schools. Inclusive education calls for the merger of regular and special education (cf. Lipsky & Gartner, 1996; Stainback, Stainback, & Ayres, 1996) and represents a shift from a continuum of educational placements to a continuum of educational services. To many, inclusive education also represents a shift from changing individuals (who must become “ready” and earn the right to be in integrated settings) to changing the curriculum and pedagogy (Taylor, 1988). To these educators, inclusion would mean the end to labeling and segregated education classes but not the end of necessary supports and services, which would follow students with special needs into the regular classroom. According to Sapon-Shevin (1994/1995), “What we need is a continuum of services.… Inclusion is saying: How can we meet children’s individual educational needs within the regular classroom context—the community of students—without segregating them?” (p. 8).

Inclusive education is becoming an ideal that many in regular education are striving for as well. For example, the National Committee on Science Education Standards and Assessment (NCSESA, 1993) has advocated an inclusive position in its call for science for all:

We emphatically reject the current situation in science education where members defined by race, ethnicity, economic status, gender, physical disability or intellectual capacity are discouraged from pursuing science and excluded from opportunities to learn science. By adopting the goal of science for all, the standards prescribe the inclusion of all students in challenging science learning opportunities and define a level of understanding that all should develop.… Every person must be brought into and given access to the ongoing conversation of science. (p. 1)

Similar statements have been made by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (1992), the Council of Chief State School Officers (1992), and the National Association of State Boards of Education (1992).

Regardless of the individual positions teachers may take regarding inclusive education, most will find themselves teaching children who vary greatly in ability, culture, language, and background. For inclusive education to be successful, fundamental changes are needed in curriculum, instructional practice, and assessment. Also needed is a redefinition of the professional relationships among general and special educators so that both children and teachers receive the necessary supports and services. The remainder of this chapter and the chapters that follow in this “Readings” section of the book are devoted to describing these fundamental changes, which will be needed to successfully include diverse populations of students in the general education classroom.

Curricular and Instructional Approaches that Facilitate Inclusion

Curricular and instructional approaches that promote the active, social construction of knowledge; that are interactive, experiential, and inquiry based; and that provide guided instruction have been recommended in the literature as ways to include and motivate students who traditionally have been excluded from success in the mainstream. Reviews of the literature on inclusive science classes, for example, concluded that an approach that emphasizes concrete, meaningful experiences and cooperative learning is more successful for students whose learning difficulties are related to language, literacy, and lack of prior knowledge than a curriculum that emphasizes vocabulary acquisition, lecture or textbook learning, and whole- group recitations (Mastropieri & Scruggs, 1992; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1994). Moll (1994) has argued that interactive, “participatory” approaches that emphasize authentic activities, guided instruction, and student ownership of learning are well suited to Latino and other children:

These “participatory” approaches highlight children as active learners, using and applying literacy as a tool for communication and for thinking. The role of the teacher is to enable and guide activities that involve students as thoughtful learners in socially meaningful tasks. Of central concern is how the teacher facilitates the students’ “taking over” or appropriating the learning activity. (p. 80)

Participatory approaches are also congruent with the cultural values and verbal interaction styles of many American Indian and Alaskan Native communities, in which shared authority among adults and children, voluntary participation, competence prior to public performance, and cooperation are the norm (Deyhle & Swisher, 1997). According to Deyhle and Swisher, these values help to explain why some American Indian children are more likely to participate actively and verbally in cooperative group projects and similar situations in which they have control in volunteering participation. In contrast, many American Indian children are less apt to participate in teacher-dominated activities such as responding on demand to a question asked in a large group:

In these “silent” classrooms, communication is controlled by the teacher, who accepts only one correct answer and singles out individuals to respond to questions for which they have little background knowledge. Many of these educators expect passivity and fail to provide Indian students ...