Biological Imaging 8

Although Foucault’s remarks on the maternal body itself are extremely limited, his analysis of biology, medicine, and techniques employed in various institutions in order to discipline the body and make it docile can be useful in analyzing the history of biological and medical theories of the maternal body.9 Analyzing the diseased body in The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault describes the processes through which the medical gaze constitutes an individual, specifically the sick individual. There he maintains that “the gaze is no longer reductive, it is, rather, that which establishes the individual in his irreducible quality” (Foucault 1975, xiv). I will indicate how the medical gaze has established the fetus as the individual and the placenta as the key to the irreducible quality of individuality itself, while the maternal body fades into the background.

In The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault traces some of the complex lines between the visible and the invisible. In contemporary medicine and biology it seems that scientists can inspect an organism and simply “see” what it is and what it does. Seeing is knowing. Yet, as Foucault points out, even with the advance of medical technologies that enable scientists and doctors to “see” parts of the human body never seen before, their seeing involves an interpretation of that which they “see.” What becomes visible through technological advances does not eliminate the invisible, rather it merely rearranges the visible and invisible. As Foucault says:

What was fundamentally invisible is suddenly offered to the brightness of the gaze, in a movement of appearance so simple, so immediate that it seems to be the natural consequence of a more highly developed experience. It is as if for the first time for thousands of years, doctors, freed at last of theories and chimeras, agreed to approach the object of their experience with the purity of an unprejudiced gaze. But the analysis must be turned around: it is the forms of invisibility that have changed. (1975, 195)

In the Preface to The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault begins his discussion by comparing Pommes mid-eighteenth-century account of his bath cure for a hysteric to Bayle’s mid-nineteenth-century account of brain lesions. Foucault points out:

Between Pomme, who carried the old myths of nervous pathology to their ultimate form, and Bayle, who described the encephalic lesions of general paralysis for an era from which I have not yet emerged, the difference is both tiny and total. For us, it is total because each of Bayle’s words, with their qualitative precision, direct our gaze into a world of constant visibility, while Pomme, lacking any perceptual base, speaks to us in the language of fantasy. But by what fundamental experience can I establish such an obvious difference below the level of our certainties, in that region from which they emerge?… From what moment, from what semantic or syntactical change, can one recognize that language has turned into rational discourse? What sharp line divides a description that depicts membranes as being like “damp parchment” [Pomme] from that other equally qualitative, equally metaphorical description of them laid out over the tunic of the brain, like a film of egg whites [Bayle]? (1975, x—xi)

As the practice of autopsy and examination of human cadavers became common in the nineteenth century, scientists no longer had to fantasize about the internal organs of the human body. Artists were no longer required to create visual representations of those organs from their imaginations. Rather, the scientists could draw, even photograph, what they saw. Medicine had moved from fantasy to truth. The invention of the microscope revealed previously hidden worlds to the scientific gaze. Even more recently, the invention of ultrasound imaging, magnetic resonance scanning devices, and various invasive scopes have made the internal workings of the living animated body available for inspection. The scientists’ metaphors, as strange as they may be, take on a truth that they could not previously have had because these technicians can “see” the object itself. As long as they are looking at it, the human body can no longer withhold its mysteries.

In the case of the maternal body, as the gaze of the physician or biologist moves from the body of the mother to images of the fetus, that fetus becomes the individual constituted through the medical gaze. As the fetus becomes more visible, the maternal body becomes more invisible. Although technology has changed over the last 2000 years, and our views on reproduction have changed dramatically, the role attributed to the maternal body in reproduction has changed very little. In fact, technological advances—and the changing focus of the gaze—have turned the mother into a subject only insofar as she has a responsibility for her child, both before and after its birth. The history of medical and biological accounts of conception and gestation construct the maternal body as a passive container that exists for the sake of the “unborn child.” And, as new technologies make it possible to view the fetus in utero, it becomes an individual, the active subject of its own gestation and birth.

Jana Sawicki, Gena Corea, and others have argued that new reproductive technology makes women subjects of their own reproductive choices as they never have been before, while at the same time subjecting them to disciplinary techniques employed through the institutions in which these technologies are developed and deployed (Sawicki 1991). And, although she does not explicitly employ a Foucaultian framework, Nancy Tuana has done excellent work to describe a history of theories of reproduction that have been used to support arguments for womens biological inferiority to men (Tuana 1993). Drawing on some of this research, I would like to take a different path. I am interested in how theories of reproduction, particularly the relationship between the maternal body and the fetus, both construct and manifest the changing discourse of the individual or person.

In the first chapter of the 1989 text book Biology of the Uterus, Elizabeth Ramsey attributes the errors in ancient representations of the uterus to the fact that no one had “set eyes on one” (in Wynn and Jollie 1989, 1). She explains:

Since the human uterus, at least in its gross anatomy, is not a particularly complicated organ, one may wonder why anyone who had once held a uterus in his hand and perhaps made a simple sagittal section through it would have failed to grasp its pattern. That of course is the crux of the matter. The early physicians did not hold the uterus in their hands; many never even set eyes on one. Religion and law forbade dissection of human bodies until surprisingly recent times, and all concepts of reproductive tract anatomy were based on findings in animals. Since most of the animals observed had duplex or bicornuate uteri, extrapolation to the human produced many erroneous and bizarre theories. (1)

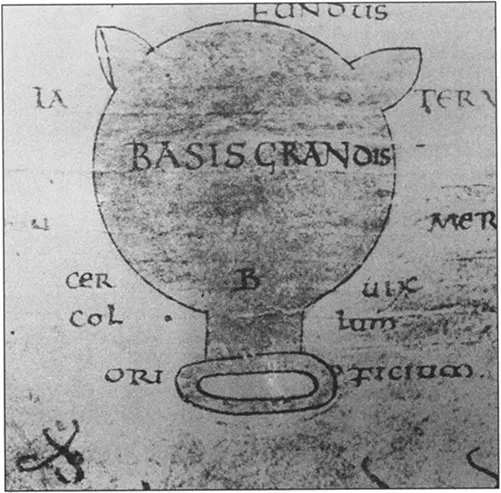

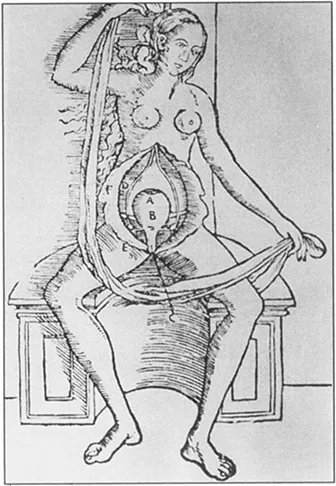

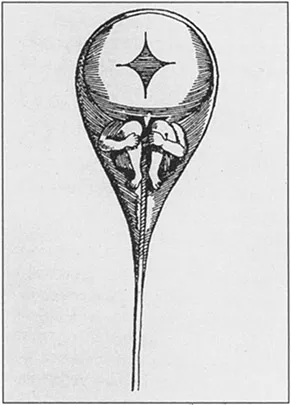

Theories of the bicornuate, or two-chambered, uterus were held through the sixteenth century. From Hippocrates in the fourth century BC through the sixteenth century, “the uterus was believed to consist of a number of cavities exhibiting angulations and horns, and its lining studded with ‘tentacles’ or suckers’” (Wynn and Jollie 1989, 1). Elizabeth Ramsey identifies the illustration in figure 1 as the earliest known representation of the uterus from the ninth century. This representation shows a circular uterus with earlike chambers at the top (fig. 1). An illustration from Mondino dei Luzzi, who, according to Ramsey, performed the first authorized public dissection of a human body for scientific purposes in 1315, still represents a compartmentalized uterus even after supposedly “setting eyes on one” (fig. 2).

Ramsey does not explain how the setting on of eyes fails to yield the pattern of this “simple organ.” Perhaps, seeing is not believing. What the scientist “sees” is affected by what he expects to see. Yet, Ramseys attitude towards the developments in biology—that seeing is knowing—seem representative of not only ancient presumptions

about medicine, but also contemporary presumptions. Luzzi held a human uterus in his hand and still saw compartments there.

Without the benefit of holding a human uterus in his hands, based on his study of animals, like Hippocrates, Aristotle believed that the human uterus had compartments. In addition, Aristotle provides one of the first known theories of the epigenesis of the embryo. He maintained that the embryo developed gradually as a result of the combination of male and female principles: “What the male contributes to generation is the form and efficient cause, while the female contributes the material” (Aristotle 1984, 729.a.10). The male principle contributes the soul while the female principle contributes the less perfect body (738.b.25). The male element creates the individual or person within the maternal body. On this account, the maternal body provides merely the fertile soil within which the male seed implants itself and grows. The female principle is passive while the male principle is active.

In the first and second centuries AD, Rome produced several important physicians who contributed to the theories of reproduction. Rufus and Soranus (both of Ephesus, eventually practicing in Rome) continued the tradition of the bicornuate uterus, while Galen improved Aristotle’s explanation of the inferiority of the female contribution in conception (see Wynn and Jollie 1989, 2–3). Like Aristotle, Galen held that both males and females have semen, but the female semen is not as “hot” as the male semen, both in its temperature and its perfection. Galen explains that “the female must have smaller, less perfect testes, and the semen generated in them must be scantier, colder, and wetter (for these things too follow of necessity from the deficient heat)” (Galen 1968, 14.11.301). Females are the result of the coldest and most impure combination of male and female elements. According to Galen, “the left testis in the male and the left uterus in the female receive blood still uncleansed, full of residues, watery and serous, and so it happens that the temperatures of the instruments themselves that receive [the blood] become different” (14.11.306). And when a seed from the left testis in the male combines with the left uterus in the female, then a female child is the impure result. Nancy Tuana notes:

Galen’s anatomical error provides the explanation, missing from the Aristotelian account, of why woman is deficient in heat. Although Aristotle based all of womans imperfections on this defect, he failed to provide any account of the mechanism that causes it. Galen’s creative anatomy provides this mechanism: the impurity of the blood out of which female seed is generated accounts for womans inferior heat. Since woman is conceived out of impure blood, she is colder than man. Due to this defect in heat, her organs of generation are not fully formed, and the seed produced by them is imperfect. (1993, 134)

As Tuana points out, Galen’s account of conception justified womens biological inferiority. Galen’s theories held with only slight modifications through the twelfth century. Sometime during the twelfth or thirteenth century physicians at the school at Salerno in Sicily developed the notion of a seven-chambered uterus (shown here in a text from the sixteenth century) (fig. 3). Expanding on Galen’s theories, they held that male embryos develop in the three right chambers, female embryos in the three left chambers, and hermaphrodite embryos in the middle chamber (see Wynn and Jollie 1989, 5).

In the seventeenth century, however, the Aristotelian doctrine of epigenesis—the doctrine that the embryo develops—was called into question. In its place, scientists began to propose theories of preformation: that the human animal is preformed in miniature and merely grows rather than develops gradually. The notion of preformation was developed in accordance with the theory that there is no generation in nature, only the growth of what is already there (see Tuana 1993, 148). Using microscopes, scientists confirmed the preformation theory. With primary access to chicken eggs, anatomists “saw” tiny organs already present in chicken embryos. They hypothesized that these organs merely grow during gestation.

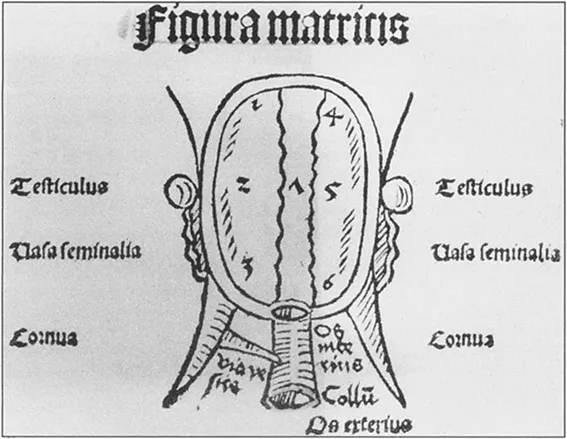

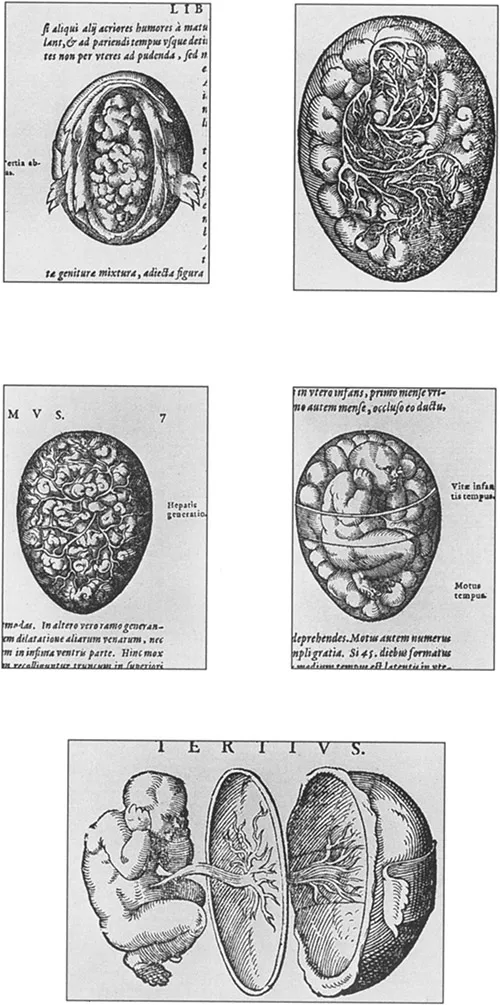

Once Louis Dominicus Hamm observed human sperm under a microscope and “saw” “spermatic animalcules,” and a new version of preformation took hold. Several other scientists claimed to confirm the findings of Hamm. In 1699 Plantade “saw” the preformed human animal in sperm under his microscope: “For while I was examining them all with care one appeared which was larger than the others, and sloughed off the skin in which it had been enclosed, and clearly revealed, free from covering, both its shins, its legs, its breast, and two arms, whilst the cast skin, when pulled further up enveloped the head after the manner of a cowl” (cited in Cole 1930, 69). In 1694 Nichlaus Hartsoeker illustrated a spermatic animalcule (fig. 4). With the theory of preformation of the “spermatic animalcule,” the male element provides both the form and the material of the child in miniature and the tiny person merely grows in the maternal womb as the seed grows in the soil. The microscope had provided proof that the male principle is superior and that all individuals exist preformed in the male element. The trouble with this theory was explaining why so many preformed individuals had to perish so that one might implant itself in the womb.

In spite of the seemingly regressive theory of preformation of the seventeenth century, the sixteenth century brought some changes in anatomical theory. Vesalius, Colombo de Cremona, and Fallopis da Modena, all eventually working in Italy, gave greater detail to theories of the uterus. Vesalius first used the terms “uterus” and “pelvis,” Colombo named the “labia,” “vagina,” and “placenta” (Colombo called the after-birth “placenta” to describe its cakelike appearance in 1559, although the word did not acquire its present meaning until the latter half of the seventeenth century) (Steven 1975, 12) and Fallopio named the Fallopian tubes (Wynn and Jollie 1989, 8–9). By this time dissection and autopsy of human cadavers was more commonly practiced. Still, the study and dissection of the pregnant maternal body was limited. Cadavers were obtained by gravediggers and from the poor who did not benefit from burial and funeral rituals. Prior to the eighteenth century, most of the theories of the operations of the uterus and placenta during pregnancy were still based on dissection of pregnant animals.

In the second century, for example, Galen had described the exposure of a living goat fetus in utero in On Anatomical Procedures (see Steven 1975, 1). He had identified four stages of embryonic development: I. coagulum of male semen and female semen (menstrual blood); 2. Formation of the heart, liver, and brain; 3. rudimentary formation of all body parts; 4. embryo fully formed. Over 1000 years later, in 1554, Jacob Rueff illustrated Galen’s theory in his De Conceptu et Generatione Hominis (fig. 5). Rueff also illustrated the attachment of the fetus to the placenta and its attachment to the uterus. This illustration was derived from Vesalius’s earlier illustrations in De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543). This drawing shows a human fetus attached to a zonary placenta which, as twentieth-century biologists have shown, is not the shape of a human placenta but rather an animal such as a dog.10 Vesalius’s early illustrations and Rueff’s copies appear to be based on observation of chicken eggs, the egglike shape, and animals with zonary placenta, the ribbon around the womb (fig. 5).

Twelve years later, Vesalius corrected his drawings to indicate the discoid placenta of the human as distinct from the zonary placenta of the dog and the multiplex placenta of the buffalo.

In the sixteenth century the debates over the nature and function of the placenta began. Until the end of the eighteenth century it was widely held that the maternal and fetal vessels were anastomosed end to end in the placenta and that the two bloodstreams were continuous (Wynn and Jollie 1989, 9). In 1587, Arantius published De Humano Foetu in which he compared the operation of the placenta to the function of the liver. He is unclear about the relation between the fetus, placenta, and maternal body. His contemporary Hieronymous Fabricius of Aquapendente published De Formato Foetu seventeen years later in which he refutes any suggestion by Arantius that the fetal and maternal blood vessels are not continuous. Following the long accepted theories of Aristotle and Galen, he maintains that the placenta acts as a kind of sealant to insure that the maternal and fetal blood vessels do not separate under the weight of the fetus; the placenta is a type of glue (Steven 1975, 7).

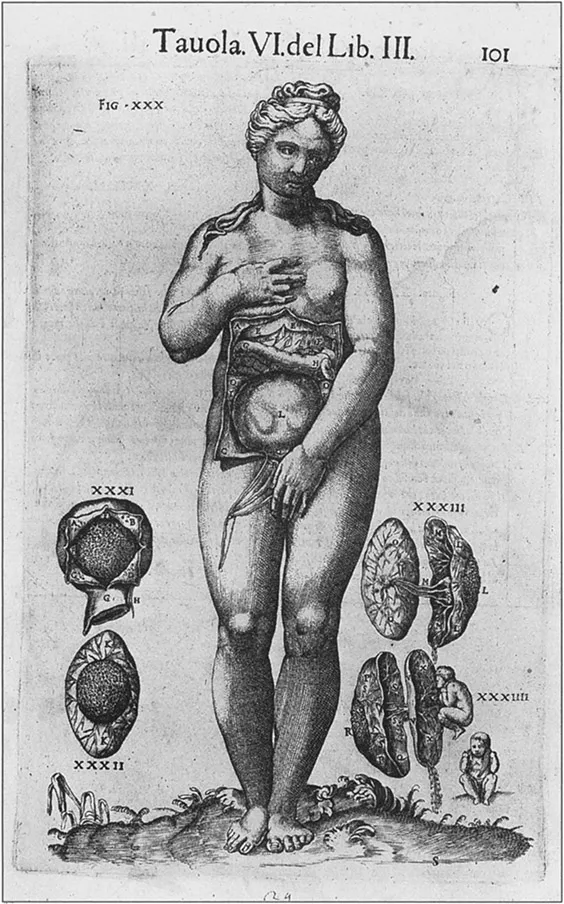

In 1626, Adrianus Spigelius published his De Formato Foetu in which he too confirms the thesis that “the umbilical vessels are roots which carry nutriment from the uterus to the foetus, and that foetal and maternal vessels are united within the substance of the placenta” (Steven 1975, 13). Spigelius’ treatise remained popular due to its elaborate illustrations prepared by the artist Julius Casserius (fig. 6). But, as human dissection became more typical in the eighteenth century, and the compound microscope had been perfected, scientists no longer needed to employ the creative imagination of the artist in order to describe and illustrate what the eye could see. Now, printed anatomies were drawn at the scene of the dissections of pregnant women (see Adams 1994, 128). Fantasy was becoming “reality.”

William Hunter’s Anatomy of the Human ...