eBook - ePub

The Complex Forest

Communities, Uncertainty, and Adaptive Collaborative Management

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Complex Forest

Communities, Uncertainty, and Adaptive Collaborative Management

About this book

The Complex Forest systematically examines the theory, processes, and early outcomes of a research and management approach called adaptive collaborative management (ACM). An alternative to positivist approaches to development and conservation that assume predictability in forest management, ACM acknowledges the complexity and unpredictability inherent in any forest community and the importance of developing solutions together with the forest peoples whose lives will be most affected by the outcomes. Building on earlier work that established the importance of flexible, collaborative approaches to sustainable forest management, The Complex Forest describes the work of ACM practitioners facing a broad range of challenges in diverse settings and attempts to identify the conditions under which ACM is most effective. Case studies of ACM in 33 forest sites in 11 countries together with Colfer's systematic comparison of results at each site indicate that human and institutional capabilities have been strengthened. In Zimbabwe, for example, the number of women involved in decisionmaking soared. In Nepal, community members detected and sanctioned dishonest community elites. In Cameroon and Bolivia, learning programs resulted in better conflict management. These are early results, but a wide range of recent research supports Colfer's belief that these new capabilities will eventually contribute to higher incomes and to sustainable improvements in the health of forests and forest peoples. The Complex Forest reinforces calls for change in the way we plan conservation and development programs, away from command-and-control approaches, toward ones that require bureaucratic flexibility and responsiveness, as well as greater local participation in setting priorities and problem solving.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

HOW ON EARTH CAN THE GLOBAL community create the conditions necessary to sustain the world's forests and forest communities? This was the question that troubled us, a group of researchers at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Bogor, Indonesia, in early 1998. We passionately wanted to help bring about forest sustainability—including its human dimension—in tropical forests and with forest peoples. In this book, we describe an approach we call adaptive collaborative management (ACM). We had just completed a successful four-year project developing and testing criteria and indicators (C&I) for sustainable forest management; another research effort was under way on devolution processes in forested environments. We felt that we had moved the global sustainability debate forward, helping create a more precise meaning for the term sustainable—a meaning that could be examined in the field. Yet we were not satisfied. We knew that we could fine-tune criteria and indicators for a very long time without changing the conditions in a single forest or among a single group of forest dwellers. We could not expect conditions in the forests to change just because we had developed more precise C&I to assess their condition. There needed to be some way to create these conditions that the C&I sets identified as critical for sustainability, in forests and forest communities, and on a broad scale.

Having spent years in humid tropical forests in Asia, supplemented by time in African and South American forests, we were very aware of the urgency of solving the environmental and human problems related to sustainability. It is tiresome to repeat the distressing figures for global forest destruction and degradation (Terborgh 1999) and the appalling losses—economic, cultural, environmental—that accrue daily to forest communities (e.g., Wickramasinghe 1994). Seeing the same processes at work in country after country is even more dismaying than reading about them. It was clear that something needed to be done quickly if we had any hope of reversing or even slowing the dramatic and destructive processes that were under way.

We chose to develop a research program to address the problems and simultaneously contribute to our scientific understanding of the processes involved. By 2002, we were working with a team of more than 90 researchers in Asia, Africa, and South America. Together, we have taken our initial ideas forward in 30 field settings. This book builds on the site-by-site analyses of the team members; without their contribution it could not have been written, and thus we are all authors. Yet it also provides conclusions based on my own systematic comparison of the results at each site. I distinguish between my own analyses and conclusions (which may or may not be shared by my colleagues) and the work of the group by shifting between first person singular and first person plural. Such an approach is not usual in scientific writing, but accuracy requires it.

In this book, I examine a range of forest community contexts from the perspectives of seven important issues and analyze the processes and outcomes. Fuller discussion of the cases and the seven issues is provided in the Appendix of Cases at the back of this book (additional, in-depth country-by-country and regional analyses are in Diaw et al. forthcoming; Fisher et al. forthcoming; Matose and Prabhu forthcoming; Hartanto et al. 2003; Kusumanto et al. 2005). This research demonstrates the fundamental importance of expanding the scientific repertoire of analytical approaches to include local variation, systems, interactions and connections among systems, and change. It also shows that scientists, policymakers, and other decision-makers must recognize (a) the inherent unpredictability of complex adaptive systems; (b) the importance of learning in our attempts to deal with this complexity; and (c) the necessity and potential for working closely with the people who act within those systems—at all levels.

A Starting Point

As we sought to act on our understanding of sustainability, we were guided by several insights that form the intellectual underpinnings of ACM (see Chapter 2). The striking complexity and diversity of forest and human systems were central in our minds (Box 1-1).1

Box 1-1. Simple, Complicated, and Complex Systems

Simple systems are those with very few elements, which behave in a readily understood and predictable manner. Complicated systems are those with many elements that, once understood, still behave in a predictable manner. Complex systems, because of internal interactions and feedback mechanisms, tend to generate “surprises” (Ruitenbeek and Cartier 2001).

These systems presented variation within a particular locale as well as incredible diversity from place to place and from time to time. We concluded that solutions to local problems would best begin at the local level. The record of decades of attempts to structure standardized solutions to local forest problems from afar is dismal (cf. Scott 1998). We concluded that complexity and diversity must be taken as givens and that recurring surprises would accompany any management effort.

Related to such complexity is the fact that in many areas, multiple management systems are at work simultaneously. A logging company may have a contract to log a large area where several ethnic groups have lived and managed the forest for centuries for multiple uses, adjacent to or even overlapping a conservation area, all overseen in some fashion by the national government. Typically, the communities’ traditional uses and management practices are ignored or criminalized. Sustainable management of the forests will, we argue, require a process of negotiation wherein the stakeholders work together to resolve local forest management problems equitably. This will require at least communication, cooperation, negotiation, and conflict management—the collaborative elements of ACM.

That local communities often have functioning or partially functioning management systems of their own is an oft-neglected aspect. In some tropical forests, the only element of sustainability in forest management is the indigenous system (e.g., Colfer et al. 2001; cf. Clay 1988; Redford and Padoch 1992). In others, the indigenous system has been systematically undermined by the state (Fairhead and Leach 1996; Leach and Mearns 1996; Peluso 1994; Bennett 2002; Sarin et al. 2003; Oyono forthcoming) but still maintains the kernels from which more sustainable practices might grow. In still other places, settlers with little knowledge of forest management (transmigrants in Indonesia, settlers in Brazil, Porro 2001) have been moved into forested areas. The differences in peoples’ forest involvement have implications for how forests should be managed. Our conclusion is that local communities represent an underutilized resource in forest management, and that they have the biggest stake in managing the forests well. Governments and industry have done badly managing many forests in the recent past; communities have been managing their forests for millennia. We were convinced that combining indigenous knowledge and motivation, on the one hand, with some outside information and some balance of power in management, on the other, could be a worthwhile approach.

We also noted the lack of feedback mechanisms in the policy context. Policy-makers often made apparently reasonable national-level plans that, when applied in particular contexts, had unanticipated effects. Granting timber concessions to foreign companies or allocating areas for national parks, for instance, has often resulted in the unintentional loss of local resources to local communities (cf. Brechin et al. 2003). Effective avenues for providing feedback about such failures (or successes) were rare. Critical opportunities to learn from failures were missed, and malfunctioning management systems continued to hobble along, either ineffective or damaging. Our experience suggested that plans rarely work as originally conceived (cf. Stacey et al. 2000) and that successful management requires regular feedback. We thought that simplified adaptations of criteria and indicators might serve at the local level as effective monitoring tools that could provide useful feedback to improve management. C&I or some other monitoring approach could form the basis for the process of social learning required for management to be responsive—the adaptive element of ACM.

Negotiated resolution of problems at local levels must be accepted at other levels. If, for instance, a community without legal rights to its traditional forest worked with a logging company in Indonesia to allocate rights to particular areas among them, the agreement would not likely be honored unless the government of Indonesia were involved. Our research, therefore, had to find links between local communities and actors at other scales—whether governments, companies, or actors like the World Bank and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). We also had to find avenues and mechanisms for effective, two-way communication between individuals and groups with vastly differing power. ACM would not work unless local communities were empowered. Indeed, empowerment has been a concern from the beginning. Disempowered groups needed a place at the negotiating table; the uneven playing field had to be leveled somehow.

CIFOR's ACM Strategy

With those issues in mind, we went to work on developing an approach to managing forests that would be consistent with those insights, address the sustainability problems of forests and forest communities, and provide results of use to others. The approach we have crafted involves three components:

1. Horizontal component. Stakeholders in a particular forest begin working together to solve the problems of that forest and the people who live in and around it.

2. Vertical component. Local communities and actors at other scales develop effective mechanisms for two-way communication, cooperation, and conflict resolution.

3. Diachronic component. The stakeholders learn together, over time, in an iterative fashion about the management of their resources and their communities.

This led to our definition of adaptive collaborative management (Box 1-2):

Box 1-2. Definition of Adaptive Collaborative Management

Adaptive collaborative management (ACM), in our usage, is a value-adding approach whereby people who have interests in a forest agree to act together to plan, observe, and learn from the implementation of their plans while recognizing that plans often fail to achieve their stated objectives. ACM is characterized by conscious efforts among such groups to communicate, collaborate, negotiate, and seek out opportunities to learn collectively about the impacts of their actions.2

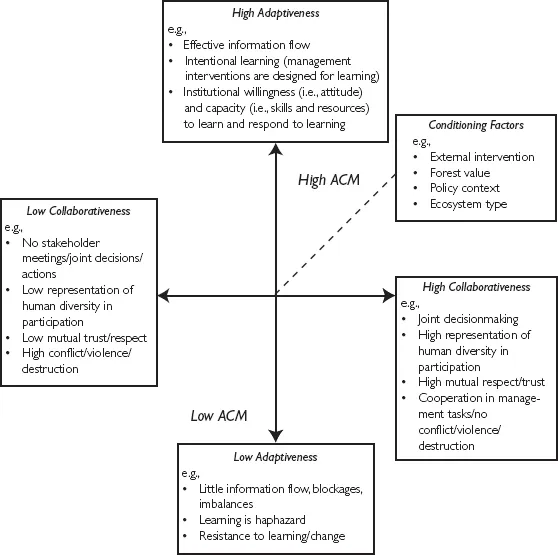

Figure 1-1 provides a graphic representation of some of the changes we anticipate as we move from one stage of adaptiveness and collaboration to another.

Our research strategy has two streams, one focused on catalyzing the ACM process in the field (the participatory action research process), and the other focused on analyzing what happens (the assessment process and strategy).

1. The Participatory Action Research Process

In a given site,3 the ACM facilitator4 has as a primary, ultimate responsibility to catalyze the process described in the ACM definition. The first task, used in both streams, is to conduct five context studies, focused on

Figure 1-1: Dimensions of ACM and Elements of High and Low Collaborativeness and Adaptiveness (McDougall 2000)

• stakeholder identification;

• historical trends;

• policy context;

• biophysical and social characteristics (based on criteria and indicators); and

• level of adaptiveness and collaboration among stakeholders.

These studies inform the ACM facilitator and protect against egregious errors based on ignorance of the local context. During this process, the facilitator establishes rapport with the community or communities involved, and prepares to conduct participatory action research. These studies are also vital to the assessment process described next.

Participatory action research drives the ACM process. The point is to catalyze a process within the local community in which the people—or some subgroup thereof—can jointly plan improvements in local conditions (sometimes in collaboration with other stakeholders), gain power and skills in dealing with others, and develop a self-monitoring system to enhance sustainability. Designed to “enhance the capacity of individuals to improve or change their own lives” (Cleaver 2002), participatory action research proceeds in a systematic, iterative mode, as shown in Figure 1-2.

This approach inevitably results in considerable variation from site to site, as will become clear in the ensuing chapters. There are many routes forward. As McDougall (2002a, 90) put it, the field teams “had the ACM elements as ‘beacons’ but were ‘making their own paths.’”

We have also had a strong interest in enhancing equity. In many ACM sites, women, particular ethnic groups, and low-ranking castes tend to be marginalized in any efforts to improve conditions. People in these categories tend to be left out of decisionmaking that directly affects their subsistence base, to have their traditionally defined ownership of and use rights to land and other resources ignored, and to be neglected when benefits are distributed to communities. One route to achieving more equitable treatment is for such disenfranchised people to develop a stronger power base in dealing with outsiders. This has meant an explicit emphasis in our work on power and its distribution and functioning. Cooke and Kothari (2002) point out that many advocates of participation have been naïve about power, and we have tried to ensure that we were not. We have expressed our interest and willingness to work with comparatively powerless groups,5 organized separate meetings for them, tutored those who will deal with powerful outsiders, provided training for transformation (based on Paulo Freire's approach), ensured equitable access to public platforms in meetings we facilitated, worked with locals (elite and nonelite) to make local political processes more transparent, required equitable representation in visits and training we funded, contributed to the public view that increased equity was desirable, and so on. Considerable effort has gone into ensuring that marginalized groups—who often have very different interests in and knowledge about forests—are included in the ACM process (Nemarundwe 2005; Mutimukuru et al. 2005; Sharma 2002; Siagian 2001; Tiani et al. 2005; Diaw and Kusumanto 2005; Pokorny et al. 2005; Sitaula 2001; Pandey 2002; Dangol 2005).

In most countries where an ACM site exists, the teams have set up national steering committees whose purpose is to ensure that the research will be useful to the country and its people. Our...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About Resources for the Future and RFF Press

- Resources for the Future

- Contents

- Foreword

- Dedication

- Acknowledgement

- 1 Introduction

- 2 ACM's Intellectual Underpinnings: A Personal Journey

- 3 Complexity, Change, and Uncertainty

- 4 Seven Analytical Dimensions

- 5 Creativity, Learning, and Equity: The Impacts

- 6 Devolution

- 7 Forest Type and Population Pressure

- 8 Management Goals

- 9 Human Diversity

- 10 Conflict and Social Capital

- 11 Catalyzing Creativity, Learning, and Equity

- 12 Commentary and Conclusions

- Appendix of Cases

- Notes

- Reference

- Acronyms

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Complex Forest by Carol J.P. Colfer, Carol J.P. Colfer,Carol J. P. Colfer, Carol J. P. Colfer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.