eBook - ePub

The Comparative Psychology of Audition

Perceiving Complex Sounds

- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Uniting scientists who study music, child language, human psychoacoustics, and animal acoustical communication, this volume examines research on the perception of complex sounds. The contributors' papers focus on finding a common principle from the comparison of the processing of complex acoustic signals. This volume emphasizes the "comparative" and the "complex" in auditory perception. Topics covered range from communication systems in mice, birds, and primates to the perception and processing of language and music by humans.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Comparative Psychology of Audition by Robert J. Dooling,Stewart H. Hulse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Hearing in the Mouse |

Universitat Konstanz, Federal Republic of Germany

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 15 years, knowledge on hearing in the mouse has grown extensively, now including not only aspects of what and how the mouse can hear (see e.g., Willott, 1983) but also strategies to perceive communication sounds and cognitive processes to evaluate their meaning. In this review, I concentrate on relationships between hearing abilities and their physiological bases and will relate to other subjects and points where comparisons become useful and stimulating.

The substrates of complex acoustic perception are complex sounds. Starting with a continuous pure tone, the most simple sound, one can increase complexity in three dimensions (spatial aspects are not considered here):

a. in the spectral domain by adding other tones higher or lower in frequency and same or different in intensity with the result of a harmonic or nonharmonic or noisy spectrum,

b. in the temporal domain by making the tone discontinuous and thus generating a temporal pattern or rhythm,

c. in the spectro-temporal domain by introducing modulations of frequency and/or intensity with the result of a time-dependent frequency spectrum and time-varying intensity distribution across the frequency components.

Natural sounds such as many animal calls and songs and speech are complex with regard to all three dimensions. And, most important, relevant information about a sender is often encoded by spectral, temporal, and spectro-temporal aspects of the sound, so that the auditory system of the receiver, primarily a conspecific individual, must be designed to analyze in all three dimensions in order to make the information available. Because an appropriate analysis is the prerequisite for sound recognition, i.e., the release of an adequate response in the receiver—the goal of all communication loops—we can expect mechanisms of complex sound perception matching with the sounds to be analyzed in all vocal animals.

In the following, hearing in the mouse is discussed with regard to analysis in all three sound dimensions. Data are used for pointing out general factors of analysis, perception and recognition of animal calls.

I. ANALYSIS IN THE SPECTRAL DOMAIN

Peripheral Filtering

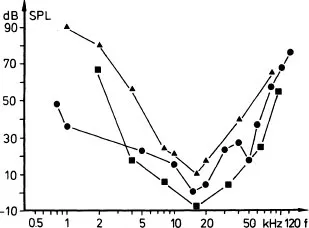

The result of the most peripheral sound analysis in the auditory system is the absolute auditory threshold curve (Ehret, 1977). The shape of the threshold curves of the mouse shown in Fig. 1.1 (Ehret, 1974, 1976a; Heffner & Masterton, 1980; Schleidt & Kickert-Magg, 1979) is typical for mammals and birds (see also Saunders & Henry, this volume). They show a bandpass characteristic and thus define the frequency range of hearing. This bandpass is established by properties of the outer, middle, and inner ear.

FIG. 1.1. Three absolute auditory threshold curves of house mice measured by different conditioning techniques. All show a sensitivity optimum between 15 and 20 kHz and good hearing in the ultrasonic range. Squares: feral mice, conditioned suppression (Heffner & Masterton, 1980); circles: albino laboratory mice NMRI outbred strain, operant reward and eyeblink response (Ehret, 1974, 1976a); triangles: albino laboratory mice, shock avoidance (Schleidt & Kickert-Magg, 1979).

The sensitivity optimum in the range of 15–20 kHz is the result of resonances of the ear canal which increase the sound pressure level within this frequency range at the tympanum by about 16 dB (Saunders & Garfinkle, 1983). Resonance frequencies of the ear canal and sensitivity optima of hearing coincide in many mammals (Shaw, 1974).

The low-frequency slope of the threshold curve is determined mainly by the size and mechanical properties of the tympanum and the oval window through which sound waves enter the cochlea (e.g., Dallos, 1973; Saunders & Garfinkle, 1983) and by the size of the helicotrema at the apex of the cochlea (Dallos, 1970). The bigger the area of the eardrum and the smaller the helicotrema are, the better is the low-frequency sensitivity and the lower is the cutoff frequency of the bandpass at the low side. Because the tympanum and the helicotrema are not specialized in the mouse (Ehret, 1977; Saunders & Garfinkle, 1983) auditory sensitivity decreases (thresholds increase) rapidly with decreasing frequency below the sensitivity optimum. The low-frequency limit of hearing may not be far below 500 Hz.

The high-frequency sensitivity and the upper frequency limit of hearing are determined by the moment of inertia and frictional losses of the osseous chain of the middle ear (Dallos, 1973; Henson, 1974) and by the construction of the cochlea at its base (near the stapes) (e.g., Bruns, 1976a; Eldredge, 1974). The mouse has a “microtype” middle ear (Fleischer, 1978; Saunders & Garfinkle, 1983) with good transmission of sound energy in the high-frequency range and a rather thick and narrow basilar membrane within the cochlea (Ehret & Frankenreiter, 1977), which is optimally suited to vibrate at high frequencies. Thus, the upper frequency limit of hearing in the mouse is beyond 100 kHz.

The absolute sensitivity level shown by the threshold curve is influenced by animal-inherent factors (anatomy and physiology of the ear) and, of course, by psychoacoustical methods of measurement. The efficiency of sound transfer through the middle ear is one major determinant. Pressure amplification by the middle ear necessary for overcoming the high input impedance of the fluid-filled cochlea is about 1:22 in man, 1:86 in the cat (Khanna & Tonndorf, 1972) and 1:30 in the mouse (Saunders & Garfinkle, 1983). This corresponds well with the differences in behavioral absolute sensitivity among these three species measured at the sensitivity optimum. With –18 dB absolute threshold level, the cat is by far the most sensitive mammal (Miller, Watson, & Covell, 1963). The threshold of the feral mouse is 10 dB higher (–8 dB; Heffner & Masterton, 1980). Because cat and mouse differ in middle ear amplification by a factor of 2.9, the mouse should be 20 log 2.9 = 9,2 dB less sensitive than the cat and this is almost exactly the case. Similarly, the –4 dB absolute threshold of man (ISO-Rec., 1961) can be calculated from the difference of middle ear amplification compared with mouse and cat.

This close agreement between relative sensitivity measurements based solely on physical properties of the outer and middle ear and relative behavioral sensitivities measured at the output of the whole auditory and motor systems of mouse, cat, and man raises an important point. The psychophysical threshold determinations obviously did justice to their name, namely, they measured the absolute sensory thresholds that directly depend on the physical properties of the systems and were not dominated by some behavioral response threshold governed by the methods of measurement (including motivational, attentional, and paradigm-dependent factors in addition to sensory ones). Every method of psychophysical threshold determination leads, under otherwise identical conditions, to its own threshold values which ideally are identical to those of the sensory system but often reflect thresholds of valuation of sensory input in the central nervous system or thresholds of the motor response. Thus, it is not surprising that seven different methods of estimation of absolute auditory threshold in the mouse produced seven basically different threshold curves (Ehret, 1983a). It follows that those measurements leading to the lowest thresholds (highest sensitivities) can be regarded as the closest approximations to the true sensory thresholds. Measurements leading to higher than absolute-threshold values are not useless because they may throw light on processes that value the contribution of sound for the release of behavior in different behavioral settings. Method-dependent threshold values are not restricted to absolute sensitivity but can be found in measurements of all sorts of auditory capabilities including difference limens, frequency and temporal resolution, and pattern recognition. We look at these perceptual abilities later.

Cochlear Filtering and the Origin of Frequency Resolution

Sound entering the cochlea via stapes motion forms traveling waves running along the fluid spaces towards the apex of the cochlea (e.g., v. Békésy, 1960). By the traveling-wave displacement of the basilar membrane, sound frequency is transformed into cochlear place. That is, sensory hair cells sitting in the organ of Corti on the basilar membrane at a certain distance from the base of the cochlea are stimulated best by sound frequencies corresponding to that place. In mammals like the mouse without prominent anatomical specialization in the cochlea, the frequency-place-transformation is proportional to a regular stiffness change of the basilar membrane from stiff (thick and narrow) at the base to elastic (thin and wide) at the apex (Ehret, 1978, 1983b; Ehret & Frankenreiter, 1977).

The frequency-place-transformation in the cochlea is the starting point for the frequency selectivity (within the hearing range) of the whole auditory system. It has been shown for the cat that the tuning of the basilar membrane displacement is as sharp as the tuning measured by tuning curves of single fibers of the auditory nerve (Khanna & Leonard, 1982, 1986). There are two populations of sensory cells in mammals, the inner hair cells (one row) and the outer hair cells (three rows) by which the tuning of the basilar membrane is transformed into response sensitivity and tuning of the auditory nerve fibers. The two hair cell populations contribute differently to information coding in the auditory nerve: Hearing is established by the function of inner hair cells (Deol & Gluecksohn-Waelsch, 1979). Also, tuning and frequency selectivity of the auditory nerve fibers are mediated by the inner hair cells (Dallos & Harris, 1978; Russel & Sellick, 1978) from which, by divergent innervation, more than 90% of the afferents in the auditory nerve originate in the mouse (Ehret, 1979a) and in other mammals (e.g., Bohne, Kenworthy, & Carr, 1982; Spoendlin, 1972). Psychophysically determined frequency selectivity deteriorates if inner hair cells are damaged but is completely normal if the outer hair cells are absent (Nienhuys & Clark, 1979; Ryan, Dallos, & McGee, 1979). Outer hair cells contribute significantly (about 30–60 dB) to the absolute sensitivity of hearing (e.g., Ehret, 1979b; Liberman, 1984; Liberman & Beil, 1979; Ryan & Dallos, 1975) and to the shape of the tuning curves of auditory nerve fibers (Dallos & Harris, 1978; Liberman & Dodds, 1984).

Thus it appears that the inner hair cells act as the elements where cochlear filtering is transformed into neural filtering making available the frequency selectivity of the cochlear place code to the central nervous system. The outer hair cells seem not to assess the bandwidths of the filters. However, they do contribute to filter shapes and control the amount of energy passed through and integrated by them (Ehret, 1979b). The result of cochlear filtering is an array of nerve fibers leaving the cochlea as filters tuned to frequencies corresponding to their place of innervation in the cochlea. Thus frequency selectivity gets a spatial dimension which is important to recognize when we consider frequency resolution of complex sound signals as the result of frequency selectivity of the cochlea.

Frequency Resolution and the Critical Band Concept of Spectral Analysis

In 1940, Fletcher conducted psychoacoustical experiments on the perception of tones in noise. He found that noise energy within certain bandwidths around the test tone contributed to masking the detection of the tone while energy outside the bandwidths did not influence tone perception. Fletcher assumed that these “critical bandwidths” of masking reflect the acuity of frequency resolution in the auditory system which is accomplished by a bank of bandpass filters with continuously variable center frequencies. Obviously, the bandwidths of the proposed filters are the critical quantities that determine the frequency r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Hearing in the Mouse

- 2. The Peripheral Auditory System in Birds: Structural and Functional Contributions to Auditory Perception

- 3. Perception of Complex Auditory Patterns by Humans

- 4. Speech Perception: Analysis of Biologically Significant Signals

- 5. Human Music Perception

- 6. Acoustic Pattern Recognition in Anuran Amphibians

- 7. The Acoustic Ecology of East African Primates and the Perception of Vocal Signals by Grey-Cheeked Mangabeys and Blue Monkeys

- 8. Species Differences in Auditory Responsiveness in Early Vocal Learning

- 9. Individual Recognition by Voice in Swallows: Signal or Perceptual Adaptation?

- 10. Dolphin Auditory Perception

- 11. Comparative Psychology and Pitch Pattern Perception in Songbirds

- 12. Salience of Frequency Modulation in Primate Communication

- 13. On Babies, Birds, Modules, and Mechanisms: A Comparative Approach to the Acquisition of Vocal Communication

- 14. Perception of Complex, Species-Specific Vocalizations by Birds and Humans

- 15. Internal Cognitive Structures Guide Birdsong Perception

- Author Index

- Subject Index