![]()

Introduction

In the first half of the nineteenth century many people anticipated that a movement of frontiersmen from the Cape Colony into south-east Africa would repeat the experience of the United States and Australia. They expected a flood of ‘pioneers’ to sweep away the indigenous people and replace them with white men's crops and herds. The story turned out very differently. Thin columns of farmers and ox wagons did push north onto the grassed plains known as the highveld and down into the lush semi-tropical lands of Natal. But African people stood much of their ground against the advancing legions of white settlement. They resisted the invaders’ diseases. They expanded trade in ivory, hides and cereal crops. They formed new groupings, reorganized old chiefdoms and joined kingdoms which succeeded in holding some of the best agricultural land. They learned new fighting skills, often adopting the invaders’ way of fighting with horses and guns. Where they did lose ground they inflicted significant casualties on the invaders and seized large herds of animals. They held most of the valuable coastal lands between East London and Delagoa Bay. They laid the foundations of the future independent African states of Botswana, Swaziland and Lesotho. They narrowly missed creating other states which might have been known as Zululand, Pediland and Gaza. By avoiding the fate of the Native Americans and the Aboriginal people of Australia, they entrenched their position as a permanent majority throughout the region. Thus, after many trials and setbacks, when democracy finally came to South Africa at the end of the twentieth century, Africans filled most of the elected positions in government.

All things considered, the period 1815 to 1854 can fairly claim to be a turning point in history.1 That is one of the reasons so many historians have tried to tell its story. Many have concentrated on the movement of white farmers and their dependants which became known as the ‘Great Trek’. Others have chronicled the bitter ‘hundred years’ war between the Xhosa and their enemies in the series of conflicts that used be known as ‘the Kaffir wars’. Some of the finest historians and anthropologists of the twentieth century tried their hands at explaining the emergence and rapid expansion of the Zulu kingdom under the legendary Shaka. The story of Moshweshwe's creation and stalwart defence of Lesotho has been told many times. The Tswana, Swazi and Pedi likewise found their eloquent historians. However, there are no comprehensive treatments of this turbulent period, except in textbooks. There is no obvious model to copy, no obvious place to begin.

This book, which seeks to view developments as part of a unified story that all South Africans can share, needs an appropriate vantage point. For various reasons it makes sense to choose one up on the highveld.

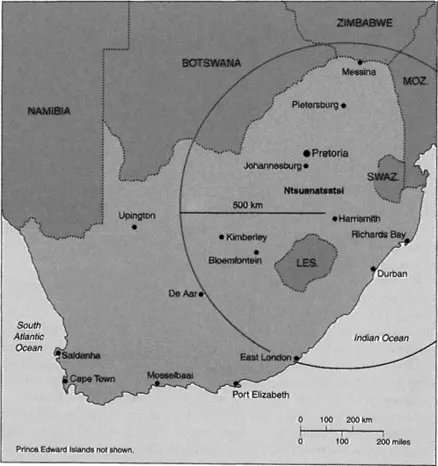

An impressive mountain looms over the town of Harrismith in South Africa. Once the home of lions, it is still a gathering place for eagles who ride rising columns of air, up and up. On a good day the updraughts will carry a soaring bird far above the summit, which itself stands more than 2000 metres above sea level. It is no great feat for an eagle to rise above the highest mountains in the nearby ranges. If the eagle could see 500 kilometres in every direction, it would see as far as Delagoa Bay in the east, across the Maloti mountains to East London in the south, to Kimberley in the west and to the headwaters of the Limpopo in the north-west. A circle drawn that big takes in all the people of Swaziland and Lesotho, most of the population of the Republic of South Africa, and the capital cities of Botswana and Mozambique. Within the same circle lie the gold and diamond mines which have so largely shaped the modern history of southern Africa – and most of the battle sites of the region's bloody wars. In this history this region will figure as the heartland of southern Africa. In an attempt to hold onto this vantage point, it will deliberately be called the heartland.

A legend says the first men and women on earth emerged from the cave of Ntsuanatsatsi, only a little distance to the north of Harrismith.2 As far as history is concerned the legend might as well be fact. Evidence dug out of the earth confirms that people with cattle have lived south of the Limpopo River since the third century of the present era.3 That is to say, since the century that saw the break-up of the Han Dynasty in China and the birth of the future Emperor Constantine in Rome – before the Anglo-Saxons arrived in Britain; before the Mayans, Incas and Aztecs built empires in Central and South America; before the first people stepped ashore in New Zealand. A very long time ago.

Why not, then, view the unfolding history of southern Africa with the eyes of the eagle soaring above Harrismith? The old histories started with

Map 1 With the eyes of an eagle

European explorers cruising along the coast – on their way to somewhere else. The story continued with the Dutch planting a station at Cape Town to supply their passing ships with fresh food. Then it followed the fortunes of the descendants of the Cape Town settlers as they expanded their ‘frontier’ eastwards. Even more recent histories, which admit that African peoples occupied the land in ancient times, soon get drawn into viewing events from behind the line of the Cape's expanding frontier of white settlement. Why? One reason is that people who lived in southern Africa during the centuries before the Dutch arrived left no records that speak to us with human voices. We know them only through the bones, tools and rubbish they left behind. When we talk about them we tend to use the language of archaeologists. They become the ‘Leonard's Kopje people’, ‘cattle-complex populations’, ‘Neolithic’ or ‘iron-age’ people. Above all they are they;not us, not like us – even if they are our own ancestors! Jan van Riebeeck and the Dutch men who came with him in 1652 left letters, journals, wills, tide deeds and all sorts of other documents that speak with voices with which we can identify, even if we first have to translate them into English. They say ‘we sailed’, ‘we landed’, ‘we trekked’, ‘we were attacked’, ‘we won’. The records make it easy to slip into seeing Africa with the eyes of the colonizer, even if all our sympathies lie with the colonized people.

Another reason why twentieth-century historians got into the habit of viewing events from behind the advancing frontier of white settlement is that powerful forces forged ways of life in the Western Cape – particularly farm life – which spread far into the interior and ruled the lives of millions of people in very recent times. It is very important to understand those forces: methods of government, land seizures, slavery, child-stealing, apprenticeship, pass laws and systems of inheritance. But the more we dwell on them, the more we tend to get caught up in the frontiersmen's view of things.

That view still affects the way we talk about places. When we talk about the Eastern Cape frontier, we mean east of Cape Town. The little word ‘trans’, meaning across, crops up everywhere: Trasorangia, meaning across the Orange River from the Cape colony; the Transkei, meaning across the Kei River, beyond the line of white settlement; the Transvaal, meaning on the far side of the Vaal River from where most white people used to live. Many other words similarly entrench the Cape settlers’ view. One is kraal, a word which probably comes from the Portuguese language and was long used to indicate the place where individual Africans lived with their families and animals (places that Africans north of the Kei River called umuzi). Another is the word assegai, a word used by the indigenous people of the Western Cape to refer to a spear (which elsewhere would be called an umkonto). So long as we use the old words, we are unconsciously referring back to Cape Town, as though all life began there.

This is the twenty-first century. South Africa is free. The descendants of the colonizers are no longer in charge of the government. Today's historians must struggle against the temptation to ride in their imaginations beside the army officers, officials, missionaries and travellers on whose evidence they must inevitably rely. We have to strive to do more than simply see out to the ‘other side of the frontier’. We need to be able to imagine ourselves in a place where the agents of colonialism appear first as specks on a distant horizon. We can get a better view if we soar with the eagles above Harrismith. From that great height all people look the same. In a fair and democratic history all people would count the same. Thus the ‘great trek’ of the Rolong from Plaatberg to Thaba Nchu and the epic journey of the Griqua over the mountains to Kokstad deserve notice alongside the more celebrated ‘great trek’ of the Afrikaner farmers and their dependants onto the highveld.

In an attempt to struggle against the old ways of thinking, this history will not use the words Transkei or Transvaal. Nor will it refer more than occasionally to ‘the Cape’ or the ‘the Cape Colony’. Since, for most of the period covered in this book, Britain claimed the territory it called the Cape Colony, that district will be called the British Zone.

It is often difficult to write democratic history because many people who lived in previous centuries left no trace of their existence. In oral traditions chiefs count more than commoners. In colonial written records officials and generals count more than subjects and soldiers. In almost all records men are more visible than women. Southern African social history in the last quarter of the twentieth century tried to counter these built-in biases and blinkers by consciously writing ‘history from below’. There will be little room for social history in this book, which by its very nature takes an Olympian perspective. How then to include those who have traditionally been excluded? One solution to the problem is suggested by the eagle who from time to time swoops down to seize a single mouse. By the use of significant anecdotes it is possible to bring the stories of women, children, forgotten peoples and outcasts sharply into focus.

Even on the clearest day, the eagle sees no national borders. The neat lines on maps which mark Lesotho off like an island in a South African sea were drawn by politicians. They also drew the long boundary which separates Mozambique from its neighbours. There was nothing natural or inevitable about the way these borders developed. They emerged as the result of life-and-death struggles for wealth and power. Change one or two events and today's maps would show an independent kingdom of Zululand. Change other things and most of what we think of as southern Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Botswana would be part of South Africa. That would have profoundly changed the way histories of South Africa are written, because the state would have included different people. Historians who think in terms of organic development of pre-destined nation-states include everyone inside the borders as part of ‘our history’. People on the other side of the fence tend to get left out. When we write about people who lived in the early nineteenth century to the east of the Drakensberg and near the western headwaters of the Limpopo, we should imitate the eagle and ignore the boundary lines on modern maps. The inhabitants of those regions were constantly interacting – grouping and regrouping. Nobody thought of themselves as Zimbabweans, Botswanans, Mozambiquans, Swazi or South Africans. In the course of this century those imaginary lines will become less and less important. As the regional economy develops, people, products, ideas and money will move freely back and forth between Swaziland and South Africa, between Zimbabwe and Botswana, between KwaZulu-Natal and southern Mozambique – just as they do within the North American Free Trade Area and the European Union. So the future will resemble the time two hundred years ago when there were no national borders.

The soaring eagle sees people but not tribes or cultures or ethnic groups. Many of the differences in language and culture which distinguish people today arose very recently. They came about through complicated interactions between individual communities and various conquerors, politicians, missionaries and scholars. In 1800 there was no Ndebele, no Swazi, no ‘Bhaca’ or ‘Shangaan’ (though of course there were people living who were the ancestors of those who later came to think of themselves as belonging to such groups). During the twentieth century powerful political and intellectual forces pushed the idea that South African history must be written as group history. At the time of the second Anglo-Boer war, journalists wrote of the conflict as a ‘race war’ between English and Afrikaner. Officials in charge of ‘Bantu affairs’ divided up the African population into a patch-work quilt of ‘tribes’, and commissioned anthropologists to write separate ethnographies for them. Gold mine bosses split their migrant work forces into teams based on ethnic affiliations and promoted ‘tribal’ dance and musical competitions. After 1948 the apartheid regime tried to convince the world that the overcrowded and degraded old Native Reserves were really ‘Homelands’ of distinct nations who would, in the fullness of time, be granted independence. People who could not be squeezed into racial or cultural pigeonholes got shoehorned into boxes marked ‘Coloured’ and ‘Asian’.

Less obviously political movements in religion, anthropology and linguistics unwittingly reinforced the idea of South Africa as a simmering cauldron of distinct cultural ingredients. Early missionaries were often the first to put African languages into writing. Their linguistic work sometimes produced new groupings. For example, in the 1830s people living near the headwaters of the Limpopo spoke virtually the same language as people living along the Caledon River. However, because different missionary societies wrote their speech down in grammars and Bibles, the world of scholarship came to accept Sesuthu and Tswana as distinct languages. Along the southeastern coast missionaries turned what had been a continuous spectrum of closely related dialects into distinct Zulu and Xhosa languages. In the twentieth century it was not missionaries but anthropologists who emerged as the pre-eminent scholarly manufacturers of cultural difference.4 Amazingly, scholars – who were mostly white people and whose first language was English or Afrikaans – told other people what tribe or culture they belonged to, how they thought, even how to write their own names.

Historians of Africa today seldom use the word ‘tribe’. It has misled too many outsiders into thinking of Africans as primitive. The word ‘people’ is the generally accepted substitute. Thus we do not write about the Zulu tribe or the Mpondo tribe, we say the Zulu people or the Mpondo people. It is important to notice some hidden dangers in this practice. The word people used in this way is a straightforward translation of the German concept of the volk, It carries the full weight of the nineteenth-century German nationalist assumption that every volk has a distinct origin in a distant past and that members of the volkshare common characteristics, common perceptions and a common destiny that others cannot share. This does not fit the evidence we have about the southern African past where social and political alignments were in a constant state of flux. Talking of ‘peoples in conflict’ or ‘cultures in conflict’ conceals a heritage of racist theory under a cloak of cultural relativi...