- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

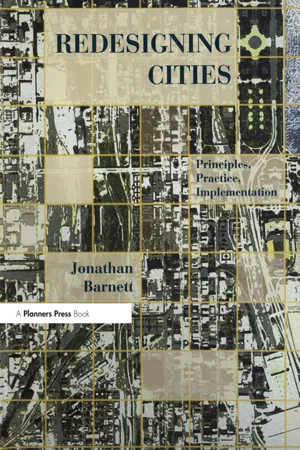

This book is recommended reading for planners preparing to take the AICP exam. Too often, no one is happy with new development: Public officials must choose among unappealing alternatives, developers are frustrated and the public is angry. But growing political support for urban design, developers' interest in community building and successful examples of redesigned cities all over the U.S. are hopeful signs of change. The author explains how design can reshape suburban growth patterns, revitalize older cities, and retrofit metropolitan areas where earlier development decisions went wrong. The author describes in detail specific techniques, materials, and technologies that should be known (but often aren't) to planners, public officials, concerned citizens, and others involved in development.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Principles

Chapter 1

Community: Life Takes Place on Foot

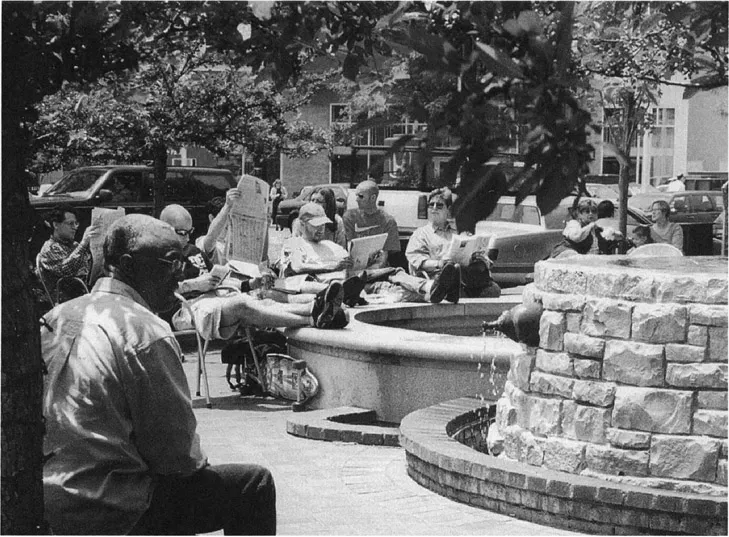

1.1 Optional and resultant activities taking place around a fountain in downtown Bethesda, Maryland. Urban design by Streetworks.

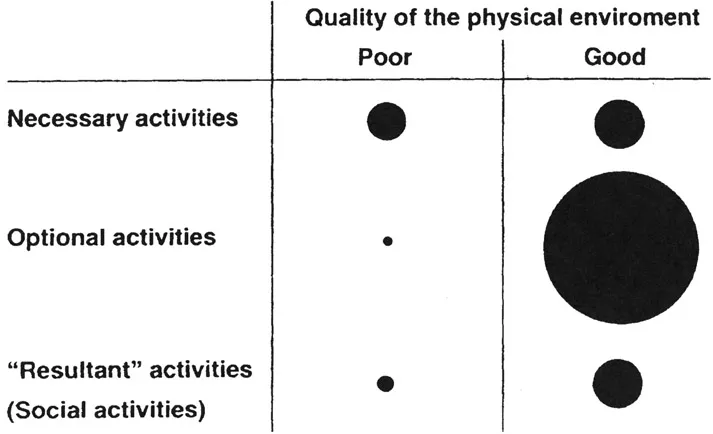

1.2 Jan Gehl’s diagram illustrating the relationship between the quality of outdoor spaces and the rate of occurrence of outdoor activities.

"Life Takes Place on Foot," is the aphorism of Jan Gehl, a Danish architect who is an acute and sympathetic observer of the way that people interact with each other and with their surroundings. He believes that people still need the casual encounters once built into daily life, but now are made less frequent by automobiles, computers, and the Internet.

Gehl has concluded that complicated human interactions can be created by a relatively simple mechanism. People pursue necessary activities that take them through public spaces. If the spaces are a poor physical environment, everyone will get through them as quickly as possible. If the environment is attractive, people will linger and engage in what Gehl calls optional activities, like sitting down for a few minutes in a cool place in summer, or a sheltered sunny spot in winter, or just slowing down and enjoying life, stopping for a cup of coffee or tea, looking at a statue or a fountain. The more optional activities there are in a public place, the more likely that there will be what Gehl calls resultant activities, that is, sociability, people meeting accidentally, or striking up a conversation with strangers. (1.1,1.2)

Gehl argues for the sociability created by traditional streets and squares, as opposed to the open spaces in most of Denmark’s modern housing projects or the big institutional parking lots where there are trafficways but few streets next to buildings. He believes that designers can make new groups of buildings that have similar characteristics to the traditional townscapes that his research finds are still successful in fostering sociability.

Gehl’s contemporary, the late William H. Whyte, studied the places where people congregate and interact in New York and other big American cities. He also argues that design can make a big difference to behavior in public places, comparing spots that are taken over by antisocial activities with those that are safe and popular. Whyte was also an amused observer of the way people act out an image of themselves in public, and interact with the image-making of others. Whyte adds two elements to Gehl’s conclusions: providing movable chairs in public places, so that people can create temporary environments for themselves, plus creating multiple activities fronting on the public space and programmed for the space. The more that is going on in and around a space, the more likely that people will be attracted, their paths will cross, and Gehl’s “resultant activities” will take place.

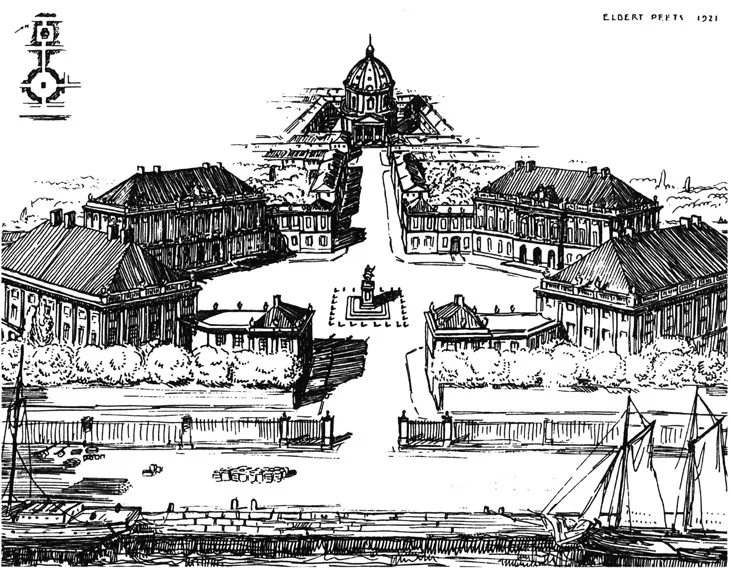

1.3 Elbert Peets’ drawing of the Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen, originally four individual houses of aristocratic families built in the late 18th century. The Marble Church in the background has its own civic square, connected by a ceremonial street to the palace. This kind of urban space is clearly a statement about power and precedence.

Kevin Lynch in his Theory of Good City Form also looked at the components of a successful public space under headings such as the way that space is perceived through the senses, and the way that the built environment fits, or doesn’t fit behavioral patterns. Lynch looks at the design of public places at a somewhat finer grain than Gehl and Whyte. He explores such questions as the functions of drama and surprise in the design of a space, and the way that people find ways to use a space not necessarily foreseen by the designer.

Richard Sennett in The Conscience of The Eye, The Design and Social Life of Cities, does not see the problem of community in cities as being one that can be solved through design. Instead he says that lack of community comes from a fear of exposure to strangers that is deeply ingrained in our culture. He intersperses his exploration of this issue in history and literature with accounts of his own walks through New York City. He recounts the deep, underlying cultural differences among various groups, and the ways that they manage to avoid interaction even when they occupy the same sidewalk. Sennett’s descriptions make it clear how few places along these walks meet even the most elementary prescriptions of Gehl, Whyte, and Lynch. Sennett may be correct about the underlying difficulties of achieving real community in public spaces, particularly in a very large city, but there are certainly many design improvements that can make public places both more pleasant and more sociable.

The Origins of Modern Public Spaces

Traditional public spaces were not designed for leisure. Market streets and squares were crowded, functional places. Fountains were meeting places because people went there to draw water for their homes. In large parts of the world these functional public spaces continue as they always have.

The plazas in front of palaces or religious buildings were intended for ceremonies. During the Renaissance, public spaces began to be embellished to create compositions in perspective, comparable to those already seen in paintings, gardens, and stage scenery. Buildings were designed to be symmetrical around a central axis, the facades were modulated by arcades and colonnades; often the same design system was applied to all the frontages around a square. Long, straight streets were planned to terminate at the center of a public building or at a plaza with a monument. Most of these innovations were about ceremony: an enhanced street environment for the carriages of the aristocracy, a place where the arrival of important people and their entrance into a palatial building would be appropriately stately and impressive. (1.3) Richard Sennett, in The Fall of Public Man, explores how many of these spaces lost their meaning as much of the ritual character of urban life has faded away.

The conversion of the Palais Royal in Paris during the 1780s into what could be called a shopping and entertainment center and the opening of London’s Vauxhall Gardens in 1732 were early examples of public places dedicated to leisure-time activities. Tivoli in Copenhagen is a descendant of the English pleasure garden, whose more recent evolution is the theme park.

The New England common in the seventeenth and eighteenth century was a staging area for cattle, it was overgrazed, dirty, and full of manure—not a green oasis with a white-painted pavilion in the center. The village green with a central bandstand is a nineteenth century innovation, as is a public park open to everyone, like Central Park in New York, where an artful mixture of formal and naturalistic design helped people from different social groups to share the space.

While arcades and shops along streets have long been places of commerce, the street as a place for a leisurely public promenade is also a mid-nineteenth century invention, the Parisian boulevards being the archetype. The European cafe with tables on the sidewalk or in the public square is a relatively recent innovation, and the pedestrian street or pedestrian district is mostly a phenomenon of the past 50 years. The Stroget in Copenhagen was one of the first shopping districts, a series of five streets closed to all but pedestrians in 1962. In Denver, Minneapolis, and a few other U.S. cities, downtown pedestrian malls remain in use, but in many other places pedestrian malls have been taken out again, as closing the streets to vehicles caused them to disappear from the mental maps of the people who once used them. In the historic centers of European cities, where public transit is much more a part of everyday life, more people live nearby, and such other options as shopping centers are still limited, the pedestrian street and plaza remain successful, particularly in countries where strolling in a public place is still a daily ritual.

Can public places in the United States attain the popularity of places in Europe that Americans go out of their way to visit when they travel?

Making Public Space Inviting

Tall buildings need space around them, and architects began designing plazas to provide an appropriate setting for towers. These plazas were not always intended to encourage people to spend time there. The idea was to create an impressive approach to the building. The owners often placed spikes on ledges so that people would not sit or lie on them, and the micro-climate was frequently unfriendly, with strong down-drafts from the building when it was windy, blinding sunlight on hot days, and large unsheltered expanses in winter.

Uninviting spaces in highly accessible locations became places for “antisocial elements” to hang out, they attracted drug-dealing, they detracted from the atmosphere of corporate dignity that the owners and architects had hoped to create. In addition, some of these public spaces had been built in response to government incentives; they were supposed to be a public benefit, not a public nuisance.

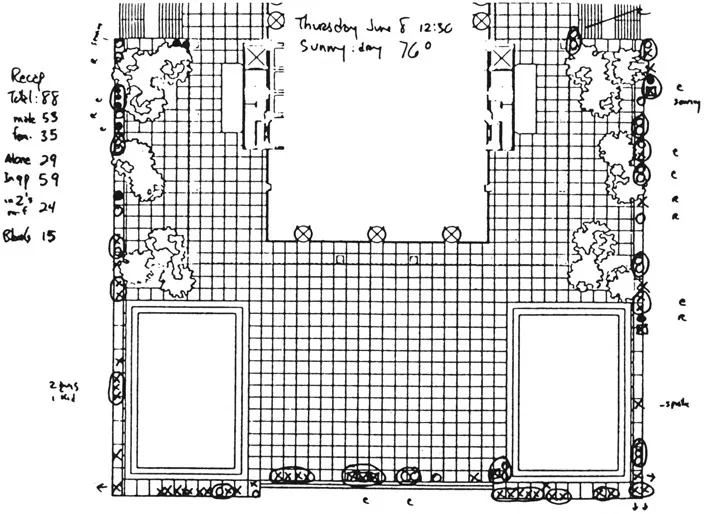

Both William H. Whyte and Jan Gehl used maps to record how people use a public space. Gehl’s map of an Italian square shows that people are comfortable standing in the arcade around the square, but not in the exposed open space itself. (1.4) Whyte’s map of the plaza in front of the Seagram building in New York shows that people like to sit on the steps and walls along the edge, where they can watch other people walking by on the sidewalks. (1.5) From observations like these it is possible to derive some general design principles, which are discussed in more detail in Chapter 12.

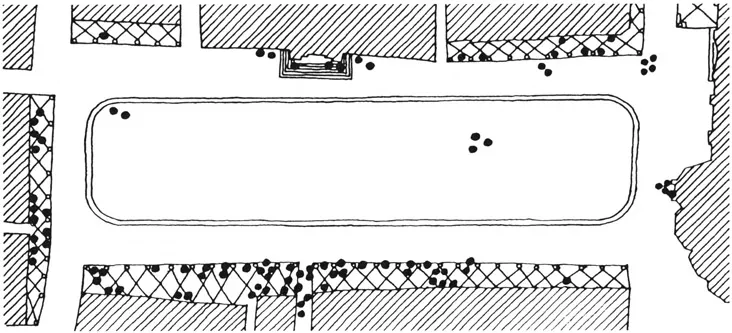

1.4 Jan Gehl’s survey of where people congregate in the city square, Ascoli Piceno, Italy. Almost everyone has chosen a protected spot around the perimeter of the square.

1.5 William H. Whyte’s map of people sitting on New York City’s Seagram Plaza during lunch hour on a mild day in June. Xs are male, Os female; a circle around Xs and Os indicates a group.

The Empty Square: Do People Still Need Public Space?

Gehl and Whyte, writing in the 1970s, discuss public spaces as questions of design, a follow-up to Jane Jacobs’s famous comparison of the active social life on her street in Greenwich Village with the deserted and dangerous lawns in a public housing project.

Today, in some parts of the world, creating a sense of community has become a larger design issue than the configuration of individual streets and public spaces. An article, “The Empty Square” by Alan Ehrenhalt in a recent Preservation magazine asks the question: “If casual social encounters are at the heart of civic life, where did everybody go?” In most U.S. cities and towns necessary activities take place using a car, and the opportunities for any kind of casual interaction are much diminished. The commute goes from the garage at home to the garage or parking lot at work. Only the journey from the car space to the lobby takes place on foot. Shopping and errands are done by car to individual destinations. Schools, churches, country clubs, restaurants, movies—each is a separate destination reachable only by car. The Courthouse Square is empty. People drive to the health club and do their walking on a treadmill.

Architects, landscape architects, and city planners are currently debating whether it is still important to create public places that permit the personal contact found in traditional cities and towns, or whether life today requires something completely different. One side, which includes the people who call themselves New Urbanists, agrees with Gehl and Whyte that traditional streets, squares, promenades, and parks are still the essence of city design. Their opponents—among whom Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas is perhaps the most articulate—believe that the idea that cities can be designed at all is based on unexamined philosophical assumptions, and that modern transportation and communication, particularly the Internet, have made traditional urban spaces obsolete. An expert on computer technology, William J. Mitchell, has written e-topia: “Urban Life, Jim- But Not as We Know It,” which observes that the interactions of technology and behavior are much too complex to allow simple apocalyptic conclusions. Mitchell notes that you have to look at the totality of people’s work and personal lives if you want to make good estimates about where new technology is taking us. Most of the people who have chosen to leave their offices and houses because the computer has freed them to work where they please are not living on mountaintops, but in smaller, rural communities, or in such sophisticated urban centers as Boston or San Francisco, precisely because of the face-to-face communication possible there. Many e-mail messages are about establishing meetings. The demand for hotel rooms and convention centers seems to be going up. Mitchell notes the rising interest in living in or near places that are rich in social interaction: older urban centers and suburban downtowns, older mixed-use neighborhoods and their modern imitations, as well as resorts. He concludes that the power of place will still prevail, that people will still gravitate to settings that offer particular cultural, scenic, and climatic attractions—"those unique qualities that cannot be pumped through a wire"—and will continue to care about meeting face-to-face.

Placemaking as a Larger Social Issue

William Leach, in his book Country of Exiles: The Destruction of Place in American Life, argues that high-speed transportation, the increasing tendencies of people to change jobs and move, the artificial environments produced by the hospitality industry, globalization policies at universities, and free trade and other international policies of government are all working to make Americans transient an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Prologue: The New Politics of Urban Design

- Part I: Principles

- Part II: Practice

- Part III: Implementation

- Glossary

- Illustration Credits

- Suggested Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Redesigning Cities by Jonathan Barnett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Aménagement urbain et paysager. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.