![]()

1

Introduction

Asplund’s distinctive contribution lies in his use of landscape architecture with architecture. It would be a mistake, however, to view this in isolation and regard it as his innovation completely. It would also be careless to overlook the importance of landscape in Swedish culture and the development of traditions in landscape architecture. Finally, the significant schools of thought in the first decades of the twentieth century, in both design and painting, should not be neglected. Though discussion of all of these subjects is offered throughout this book, this introduction is intended to offer essential background for those who come to this subject for the first time.

Through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Sweden established a new identity that was distinctive in Western Europe. This was a process that was prompted by different crises that redirected attention to the most important national priorities. First, there was the loss of Finland in 1809, a traditional part of Sweden since the Middle Ages. In reaction to this event, Esaias Tegnér wrote, “Weep Svea for what you have lost; but protect what you have . . . [W]ithin Sweden’s borders win Finland once again” (Barton 2005, 318). One of the most productive responses to this appeal was to found a nationalism that “drew less upon history than upon the quiet beauties of the Swedish landscape and Sweden’s ancient folk culture” (319). This was again the departure point when there was a national discussion after Norway renounced the union with Sweden in 1905. Ellen Key, an intellectual engaged in social reform, wished at the time to find new purpose in “the true Swedish sentiment,” which was “the deep, shy, taciturn, modest love of (our) homeland, the earth-bound feeling for our forest-scented home place” (320). On both occasions, the prevailing response was an introspective appreciation of the landscape of the home country associated with reflection on what Sweden should be in the future.

It is important to bear this history in mind as landscape architecture moves from the exclusive domain of the aristocracy in the nineteenth century to become a popular form. Particularly beginning in the late nineteenth century, new social agendas and priorities were expressed through an affiliation with landscape. Asplund’s achievement was to recognize this reality and to escape the possibility of deadening conformity associated with nationalist themes. In this respect, he showed how the Swedish condition could be reinterpreted through the classical tradition and later through Functionalist thinking from abroad. In addition to opening a national preoccupation with landscape to other influences, he also demonstrated that a progressive conception of Sweden could be understood through landscape by inviting active imagination. In effect, you could be Swedish not only by taking pleasure in the sensual and reaffirming qualities of landscape but also through reflecting on poetic associations between culture, human bodies, and the natural world.

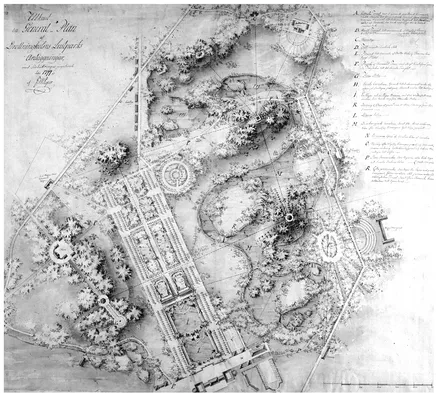

While modern landscape architecture in Sweden became more responsive to the place, it was more faithful to foreign models in earlier periods. In particular, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the influence was French. Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, the court architect from 1681 to 1728, learned the art of landscape architecture through an association with Le Nôtre and a very close reading of A. J. Dézallier d’Argenville’s Le Theorie et la practique du jardinage (Olausson 1997, 267). His most significant commission was the design for the gardens of Drottingholm Palace, located to the west of Stockholm, beginning in 1680 (Figure 1.1). Though Tessin was faithful to a fault to his French examples, he still faced the problem of adapting the French parterre garden to the Swedish landscape and climate; he was creative through necessity, not through any gift of imagination. Repeated blasting was required to adequately prepare the landscape for the axial garden. When a particular outcrop resisted all attempts at blasting, Tessin decided that an edifice with a cascade over the natural rock was the best solution (271). Though French gardens of the period invariably had fountains and canals, Tessin prudently chose to omit them entirely from the project. Though he practiced in the French manner for his public projects, his own private garden was Italian in inspiration. Called a locus ameonus, this was a modest place of refuge with “box hedge patterns, trimmed bushes and urns” as well as “a nympheum with a pair of sculptures of Greek philosophers.” Here he sought an illusion of a larger space with frescoes of landscapes, analogous to those of Claude Lorrain or Poussin (Karling 1981, 13).

Following Tessin’s death, leadership in landscape architecture in the early eighteenth century passed to Carl Hårleman. He practiced in an updated Rococo style that made some accommodation to the larger natural environment. Grass patterns were used for parterres; some rocky areas were treated artfully instead of being erased, and kitchen gardens were treated with some prominence (Karling 1981, 17). At Ulriksdal, he even created a small “natural park” at the south edge of the parterre. “This is an early, indeed the very earliest instance of natural scenery immediately adjoining a pleasure park in Sweden” (18). Another novel device used by Hårleman was the “look-out point,” used at Stola Manor, “marked by memorial stones, on a hill in the immediate vicinity of the manor” (19). Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie had also designed one at Ulriksdal with “Italian style temple-like edifices.” At Rosersberg in Uppland, Bengt Oxenstierna gave the idea a Nordic emphasis by redesigning the top of a prehistoric burial mound with rune stones and an arrangement of conifers (19).

FIGURE 1.1 View of the Drottningholm Palace Gardens, Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, 1680–1728

Source: Gustav Heurlin photo, Västergötlandsmuseet, 1M16-B63630075

After Hårleman’s death in 1753, Swedish landscape architecture languished under the leadership of Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz, who departed from the Rococo in favor of a more austere classical manner. This trend changed with the beginning of the reign of Gustav III in 1766. The young king had been educated in the fine arts and landscape architecture by Tessin’s son Carl Gustaf. In particular, he had been encouraged to take an interest in Italian gardens and the English Picturesque (Olausson 1997, 272). When the young king made it clear that he wanted a garden in the English manner built on the marshy ground to the north of Tessin’s Drottingholm garden, Adelcrantz knew that he was not up to the task. He advised the king to support Fredrik Magnus Piper, a young architect, in his studies of gardens in England and Italy, with the expectation that he would have the necessary skill and imagination to undertake the king’s project. As Magnus Olausson makes clear, Piper’s career marked a turning point in the history of Swedish landscape architecture because he could work imaginatively within an international style without the slavish eclecticism of his predecessors, despite the king’s requests for some direct references to examples in Italy and England (276).

During Piper’s time in England, he made a lengthy study of Stourhead, in particular, documenting all aspects of the garden. He also worked for a period with William Chambers, the architect of the improvements at Kew and author of A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening.1 Chambers wished to distinguish himself from the approach of Capability Brown by advocating a greater role for art and imagination. “Where twining serpentine walks, scattering shrubs, digging holes to raise mole-hills and ringing never-ceasing changes on lawns, groves and thickets, is called Gardening, it matters little who are the Gardeners” (Hunt and Willis 1993, 322). Through his experience of Chinese gardens, he found that, though their artists have “nature for their model, yet they are not so attached to her as to exclude all appearance of art” (Chambers 1773, 13).

The Chinese are therefore no enemies to straight lines: because they are, generally speaking, productive of grandeur, which often cannot be attained without them: nor have they any aversion to regular geometric figures, which they say are beautiful in themselves, and well suited to small compositions, where the luxuriant irregularities of nature would fill up and embarrass the parts they should adorn.

(Chambers 1773, 14)

FIGURE 1.2 Plan of Drottningholm Palace Gardens, Fredrick Magnus Piper, 1797

Source: Konstakademien

Chambers goes on to explain that neither too great an adherence to nature nor artfulness is appropriate. “One manner is absurd; the other insipid and vulgar: a judicious mixture of both would certainly be more perfect than either” (viii).

It is possible to see a realization of Chambers’s dictum in the superimposition of lines of radiating lime trees over a meandering canal and an island at Gustav III’s picturesque park at Drottingholm (Figure 1.2). One kind of artifice related to making multiple view corridors of the mound on the island has been overlaid on another related to the manipulation of the canals in a picturesque way. A viewer circulating around the island enjoys the repetitive framed inward views of the mound and multiple outward views of different objects in a picturesque landscape. A monumental statement of landscape architecture, a role usually taken by a building, becomes the element that asserts hierarchy and organizes the experience of the garden.

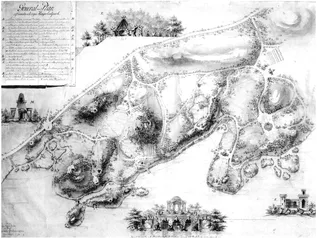

The pleasure garden at Haga, also commissioned by Gustav III, is different and less obvious as an exemplar of Chambers’s principles.2 “The Great Pelouse,” a grand bowl-like lawn that slopes towards the Brunnsviken, is the organizing space of the garden (Figure 1.3). Assorted pavilions of exotic design have been placed at oblique angles so none commands the lawn exclusively (Figure 1.4). Buildings of a larger scale, such as Gustav III ‘s unfinished Great Palace and Haga Slott, have been concealed in the woodland. Of the many pavilions, those with the pride of place are the Cooper Tents, designed by L. J. Desprez in 1787 (Figure 1.5). These extraordinary structures would later draw the attention of Asplund and fellow Neoclassicists more than one hundred years later and become a reference point for buildings at the Stockholm Exhibition and the Woodland Cemetery.

Karling notes that Piper was also involved with modifications to Kungsträdgården, near the palace in Stockholm, as well as Logården. These were efforts to make the gardens more accessible to people from all classes. “In this way Piper opened the way for the social breakthrough in landscape design which can be said to have come with the development of town parks in the nineteenth century” (Karling 1981, 35). These town parks were created as part of a larger movement called National Romanticism that had its roots among classical scholars in the early nineteenth century. Among these authors, Erik Gustaf Geijer (1783–1847), a poet, composer, historian, philosopher, and politician, was the most significant figure. In his History of the Swedish People, he consciously writes of the Baltic as a northern version of the Mediterranean and Sweden as a cradle of Baltic civilization, analogous to Greece (Geijer 1845, 3). He also did not fail to note the common traits between Norse and Greek mythology and “the principle of tragic irony which pervades the whole mythical scheme” (6). Geijer made an even more significant contribution as the founder of the Gothic Society, named after the people who inhabited Sweden originally. This was a group of intellectuals who campaigned for a broad cultural revival based on history, folktales, poetry, and songs. “Its imperative, cultural, not political, was to preserve Sweden’s ethnic heritage, highlighting cultural similarities that transcended regional identity and social class” (Facos 1998, 32).

FIGURE 1.3 The “Great Pelouse,” Haga Park, Fredrick Magnus Piper, 1781–87

Source: Peter Isotalo photo, 2007

FIGURE 1.4 Haga Park site plan, Fredrik Magnus Piper, 1781

Source: Broschyren “Hagapromenader”

FIGURE 1.5 Copper Tents, Haga Park, Jean Louis Desprez, Solna, 1787

Source: Gustav Heurlin photo, 1924, Västergötlandsmuseet, 1M16-B63625074

The other leading member of the Gothic Society was the aforementioned Esaias Tegnér (1782–1846), the most celebrated Swedish ...