![]()

Malik is an excellent example of the many African American students who are not successful academically. We first met Malik when he was a preschooler. Malik is African American and a speaker of African American English (AAE). This book is about the language of African American students, and thus about Malik and all the other school-aged African American children we have met, studied, enjoyed, and worried about over the last decade.

Malik resided in a low-income home in an urban-fringe community in the Metropolitan Detroit area. He lived with his mother, a single parent who worked as a blue collar civil servant. His family had lived in Michigan for three generations. Like most 4-year-olds, when we met Malik he was an energetic and enthusiastic child, and thoroughly enjoyed his interactions with our adult examiners.

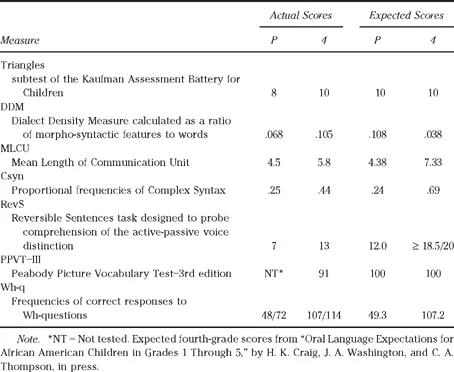

Like other African American students, Malik's performances on all of our oral language measures showed growth across grades. As a preschooler, Malik's general cognitive abilities were average (Standard Score of 10 compared to Mean Standard Score of 10) as measured by the Triangles subtest of the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (K-ABC, Kaufman & Kaufman, 1983). Malik's use of AAE was measured with a Dialect Density Measure (DDM), calculated as the rate of feature production per words (Craig, Washington, & Thompson-Porter, 1998a). He was a speaker of AAE, and was a moderate to heavy dialect user (see chapter 5 for more detail on ranges of DDMs). In contrast to most of his peers, across grades he showed no evi-dence of dialect shifting toward SAE (see chapter 5). Rather, his use of dialect appeared to increase over time (see Table 1.1).

All classrooms are language based. Oral language skills provide the foundation for the development of reading and writing (Catts, 1991; Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomblin, 1999; Snow & Tabors, 1993). Consequently, children who have difficulty acquiring spoken language skills or who speak a different variety of English other than that of the majority population are at risk for failure to acquire proficient reading skills. Many elementary-grade African American students speak AAE (Craig & Washington, 2002). AAE is a systematic, rule-governed linguistic variety of English (Baugh, 1983; Labov, 1972; Mufwene, Rickford, Bailey, & Baugh, 1998; Smitherman, 1977; Stockman, 1996; Washington & Craig, 1994; Wolfram & Fasold, 1974). AAE morpho-syntactic, phonological, lexical, prosodic, and discourse features differ considerably from Standard American English (SAE) and formal SAE, sometimes called School English (SE) or Mainstream Classroom English (MCE), is the language of the classroom and curriculum (Dillard, 1972; Hester, 1996; Labov, 1998; Morgan, 1998; Smitherman, 1998; Wolfram, 1994).

TABLE 1.1

Malik's Oral Language and Cognitive Performance Scores at Preschool (P) and Grade 4

Like most of the typically developing African American students participating in our research program, Malik's oral language skills were within the average range at preschool and grew somewhat as he got older. Malik's oral language skills are summarized for preschool and fourth grade in Table 1.1. His performance on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test III (PPVT—III, Dunn & Dunn, 1997) revealed borderline low average responses (Standard Score of 91 compared to a Mean Standard Score of 100) on this receptive vocabulary test. His receptive grammar skills also seemed low average at best, as evidenced by his failure to consistently distinguish the active-passive sentence distinction when presented a reversible sentences task (RevS, Craig, Washington, & Thompson-Porter, 1998b). Most students were able to consistently comprehend active from passive syntactic sentence structures and performed at ceiling on this task by first grade, whereas Malik had not gained this level of understanding by fourth grade.

On other oral language measures, his performances were comparable to his African American grade-level peers, showing increases in performance levels across the elementary years. This included his average sentence length, measured as Mean Length of Communication Unit (MLCU), proportional frequencies of complex syntactic structures relative to Communication Units (Csyn), and frequencies of correct responses to increasingly challenging requests for information in the form of wh-question responses (Wh-q). Each of these measures is discussed in more detail in chapters 6 and 7.

Like many African American students, as we followed Malik's progress throughout the elementary grades, it became clear that his academic achievement was low, and was declining relative to expectations with increasing grades. For reading, his Oral Reading Quotient (ORQ) from the Gray Oral Reading Test, 3rd edition (Wiederholt & Bryant, 1992) was low average in second grade (ORQ = 91), and below average (ORQ = 85) in fourth grade (mean ORQ = 100).

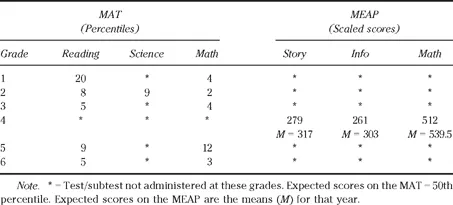

In addition, Table 1.2 presents Malik's performances on the Metropolitan Achievement Tests (MAT, 1993), a nationally standardized achievement test, and on the Michigan Educational Assessment Program (MEAP, 1999–2000), a statewide criterion referenced test that is administered beginning in fourth grade. Malik's scores on these instruments revealed poor across-the-board performances. For example, on the reading portion of the test, his achievement was best at first grade, but even this performance was only at the 20th percentile. Expected performances would be around the 50th percentile at each grade. As elementary grade levels increased, his percentile scores decreased. On the MEAP, Malik's Math score was nearly one standard deviation below the mean and his Story and Information scores, both measures of reading proficiency, were more than one standard deviation below the mean for the cohort of Michigan fourth graders who took the MEAP that year.

TABLE 1.2

Malik's Scores for the MAT and the MEAP

Questionnaires tapped the classroom teacher's perceptions of Malik's abilities. At fourth grade Malik's teacher indicated that he had great difficulty expressing himself and in comprehending, but she rated reading as only of average difficulty for him. She characterized his overall classroom performance as “below average” compared to other children in his class and felt that he did not play well with other children. Her expectations were that Malik would likely complete high school but it was unlikely that he would attend college.

In contrast, at fourth grade Malik's mother felt that it was “very easy” for him to express himself and he had no difficulty comprehending. She felt that all academic areas were important, ranking reading and science as extremely important. His mother felt that Malik found all academic subjects to be easy. She was sure that he would both graduate high school and college, and rated his classroom performance overall as “average.” When asked: what would you like your child to be when he grows up? She responded: “It doesn't matter as long as he gets an education.” (More information about differences in student, parent, and teacher perceptions is presented in chapter 8.)

Students like Malik are the reason that we wrote this book. Improving understanding of the reasons why the educational outcomes of Malik and other young African American students are poor is the motivation that underlies our intensive program of research at the University of Michigan. We are deeply concerned that in the earliest years of this the 21st century, Malik and many of his peers are unlikely to learn to read, as well as unlikely to be highly educated or prosperous as they grow into adulthood. These same students are no better off now than if they had been growing up in the United States in the early years of the 20th century.

Like many of his African American peers around the country, Malik is struggling to learn to read. Good reading skills are foundational to learning across the academic content areas. Malik and his African American peers are part of the Black—White Achievement Gap. They perform significantly lower than majority students in reading, science, math, and geography (Braswell, Daane, & Grigg, 2003; Grigg, Daane, Jin, & Campbell, 2003; O'Sullivan, Lauko, Grigg, Qian, & Zhang, 2003; Weiss, Lutkus, Hildebrant, & Johnson, 2002). Labeled the “Black—White Test Score Gap” (Jencks & Phillips, 1998), this disparity is measurable at school entry and continues through 12th grade (Phillips, Crouse, & Ralph, 1998). Moreover, recorded as early as 1910 (Fishback & Baskin, 1991), the Black—White Achievement Gap has persistently spanned generations of U.S. students.

If Malik had been a student during the early 1900s, he would have been enrolled in a predominantly African American school, and few resources would have been available to that school. Desegregation was society's ultimate response to bridging the gap between educational opportunities afforded to mainstream versus African American students. It was believed that by allowing African American students to attend schools with their majority peers, educational opportunity and equality would result. This has not been the case.

In addition to desegregation efforts, state and federal preschool programs represent an additional response designed to bridge the gap between low-income, minority students entering school and their majority peers. At the time when we met Malik he was enrolled in a classroom in Michigan's School Readiness Program (MSRP). In an investigation of the impact of these early intervention programs on later classroom performance we found that participation in public preschool programs can succeed in equalizing the starting point for many African American children (Craig, Connor, & Washington, 2003). Unfortunately, for Malik and many others like him, enrolling in these early childhood education programs is no guarantee of later academic success.

Fifty years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education (1954), African American students are no longer in “separate” schools and, African American students remain “unequal” in academic attainment and in access to high-quality educations. Twenty-five years after Martin Luther King Junior Elementary School Children v. Ann Arbor School District Board (1979), African American students continue to have difficulty learning to read. The latter case is more commonly referred to as the Ann Arbor Decision, or the Black English Case. The judge found that the dialect spoken by the African American students in the case constituted a barrier between the children and the teachers, because of failure of the teachers to take dialect into account when teaching the students to read SAE. This failure was found to be due to failure by the School Board to develop a program to assist the teachers, and the School Board was required to develop and file an appropriate plan of action to address this shortcoming. The students' reading problems, experienced by all African American students in the case, were found to impede their equal participation in the school's educational program. Today urban schools enroll the greatest numbers of African American students, and regrettably, despite attempts by the states to equalize funding across districts (Headlee Amendment, 1978) and to attract the best teachers, these schools continue to have the fewest resources and worst teachers (Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998). Lower levels of academic achievement for African American students translate into lower adult literacy levels, lower earnings, higher levels of unemployment, and higher rates of poverty (Fishback & Baskin, 1991; Jencks & Phillips, 1998; Sable, 1998). Malik is struggling, and research suggests that he is like his peers nationally. However, Malik is not a statistic; he is a child. We need to understand why the Black—White Achievement Gap is so intractable. Past explanations for the Black—White Achievement Gap have focused primarily on the role of poverty in low achievement, and the nature of early literacy learning experiences for African American students. Our research indicates that dialect has explanatory potential as well, and this is discussed in more depth in chapter 9.

Over the last decade, our program of research has contributed in substantive ways to improving current understanding of the language and literacy skills of African American students. This book is monograph like, attempting to highlight, synthesize, and consolidate our contributions to this important body of knowledge. We have written this book for teachers, practicing clinicians, and students in training to become speech—language pathologists. The research that supports our interpretive synthesis is available in journals and each issue is appropriately referenced so that the reader can pursue the details that underpin particular issues of interest.

It has been a privilege in conducting this program of research to work with a very talented, cross-racial group of staff and students. We believe that this cross-racial collaborative has strengthened the research process. African American and White researchers often faced our research agenda with different world views, cultural assumptions, and varying priorities for finding answers to the research questions posed. What every individual shared, however, was a commitment to helping all children reach their academic potential. Examining the language of African American students from preschool through fifth grade has been our tactic, and this book describes these efforts and our findings. At the University of Michigan, residing in Ann Arbor, we live less than an hour from Metropolitan Detroit. Every researcher in our program agrees that as members of a great public university and living so close to a large urban setting where large numbers of students are failing academically, that we have a special responsibility to be involved in improving understanding of the Black—White Achievement problem. As one of our team has said: How can we live so close to Detroit and not care what happens to the city's children?

This book describes our research program in terms of its participants and methods, and then organizes our findings relative to oral language and literacy outcomes. We hope that the issues raised in this book are of interest to broad segments of society. We believe that this information will prove valuable to teachers and practicing clinicians whether they have responsibility for educating one African American student like Malik, or many.

1Although Malik represents a real child this was not his name. His name was changed to preserve confidentiality.

![]()

This chapter provides a brief overview of the major lines of research focusing on African American children who speak AAE. No line of research is exclusively associated with a single scholar or language laboratory. Whereas the study of child AAE speakers is a fairly recent focus for intensive inquiry, most researchers have had to address issues framed within more than one major line of research at one time or another, as they lay the groundwork for their own research programs. This cross-fertilization of ideas, questions, and methods has led to tremendous growth in our understanding of the African Ame...