- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Turf Management

About this book

Many leisure activities involve the use of turf as a surface. Grass surfaces on golf courses, bowling clubs, cricket pitches, racetracks, and parks all require maintenance by trained personnel.

International Turf Management Handbook is written by a team of international experts. It covers all aspects of turf management and in particular

* the selection and establishment of grass varieties

* soils, irrigation and drainage

* performance testing and playing qualities

* issues relating to specific playing surfaces

In its depth of coverage and detailed practical advice from around the world this comprehensive handbook is destined to become the standard reference work on the subject.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Turf Management by David Aldous in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to turfgrass science and management

Introduction

Turf comes from either the ancient Sanskrit word, darbha, or the old English word, torfa, both meaning a tuft of grass. More modern definitions cite turf as a surface layer of vegetation, consisting of earth and a dense stand of grasses and roots. In profile, turf consists of verdure, the green aerial shoots remaining after mowing; thatch, the intermingled layer of dead and living stems and roots that develops between the verdure but above the soil surface; and soil, which contains underground stems and roots. Other terms used synonymously with turf include sod, which is a piece cut from this vegetative material plus its adhering soil; sward, which is the grassy vegetation often used in association with pastures; grass, which is any monocotyledonous plant belonging to the family Poaceae; a green, which is a smooth, grassy area used for sporting purposes; and a lawn, which had been defined as a flat and usually level area of mown grass.

Turfgrass science and management involves the art, culture and science of managing these natural grass surfaces. All turf managers aim for the best playing conditions and turf of the highest quality. Playing quality is a function of the natural grass surface and soil conditions in the field, and has a great influence on traction, impact absorbence and ball response. Measurable playing standards are now in place for many natural grass surfaces (Canaway et al., 1990). Turfgrass quality involves a composite, visual assessment of the natural grass surface, and has established standards against which performance is measured (Beard, 1973).

Benefits derived from the turfgrass community

Living turf provides considerable aesthetic, ecological, functional, recreational and social benefits. Functional and ecological benefits include improved soil stabilisation at the surface by reducing the potential for erosion and wind blown soil particles, and acting as a filter for improving the quality of groundwater. In addition, turf can substantially influence heat loss, reduce noise, glare and visual pollution, and act as a safe, low cost impact surface for many sporting and recreational surfaces, highways and roadsides (Beard, 1973; Roberts, 1985; Beard and Green, 1994). Actively growing turf also maintains the fundamental abiotic components of the world’s life support systems, such as air, soil and water (Carne, 1994).

In urban environments, plants generally modify temperatures by influencing the rate of energy exchange (Mastalerz and Oliver, 1974). Grasses transpire at a rate that, in energy terms, exceeds the local radiant energy supply. If a substantial portion of this heat load is not dissipated through the processes of evapotranspiration, reradiation, conduction and convection, temperatures at the surface of the leaf can reach lethal levels. Energy not dissipated remains to affect the specific heat balance and temperature of the leaf. Factors that influence the temperature of the leaf canopy are ambient air temperature, relative humidity, availability of soil moisture, and wind velocity. Under warm to hot conditions, the leaf surface may be up to 20°C cooler than nearby unprotected buildings or road surfaces. Finnigan et al. (1994) found that effective tree cover ameliorated the local temperatures and humidity by up to twice the regional average, with reductions of 4°C when compared to average temperatures of 30°C. Gibbs (1997) compared the temperatures between natural and synthetic bowling green surfaces, and found that the air temperatures were only likely to be large when the ambient air temperatures rose above 20°C. Surface temperatures of 60°C have been recorded on synthetic turf, alongside maximum temperatures for natural grass of 32°C (Mecklenburg et al., 1972). Tree cover can also reduce surface temperatures by up to 15°C (Givoni, 1991), and can cool adjacent turf by conduction. Lowering the height of cut of turf will also influence surface soil temperatures. For example, soil temperature extremes are greater under a turf cut at four millimeters than at 37 millimetres. Research has shown that strategically placed vegetation can reduce noise levels by 15 to 45 per cent at distances of 9 to 21 metres (30 to 70 feet) along heavily used urban freeways, as well as reduce glare and associated eye discomfort from reflected light (Beard, 1977).

Turf provides a recreational benefit by providing a low-cost, low-impact, safe surface for many outdoor sport and leisure activities. Psychologically, aesthetically pleasing, green turf enhances the beauty and attractiveness of a landscape by improving mental health and work productivity, as well as providing an overall better quality of life. Sociological benefits can also accrue to the individual and to the general community when people interact with plants. Relf and Dorn (1995) and Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) have shown that interacting with plants can develop an improved sense of self worth, create new friendships and social placement, as well as provide feelings of freedom and being in control of one’s life. Researchers have also documented that people who interact with plants can recover more quickly from everyday stresses (Bennett and Swasey, 1996) and show improved self esteem (Smith and Aldous, 1994). Nursing home clients who care for plants have shown an improvement in alertness, participation and well-being (Langer and Rodin, 1976), and display a more positive outlook on life (Ulrich, 1990).

Historical perspectives in turfgrass

References in the early scriptures make frequent mention of fields of grass and ornamental gardens set in idyllic situations. Genesis (1: 11–12) makes mention, ‘And God said, let the earth bring forth grass,… And the earth brought forth grass. . .'. The ornamental gardens of Emperor Babar and Chosroes I of Persia (AD 531–579) have been illustrated in the weave of early Persian garden carpets (Rohde, 1927). Gardens have long been expressions of luxury, such as the gardens of one of China’s early emperors, Wu Ti (157–87 BC) (Malone, 1934); for pleasure, such as the Indian Taj Mahal and its surrounding gardens (Goethe, 1955), and as an expression of affection. For example Shah Jahan, the Grand Mogul, developed a number of ornamental gardens as an expression of love for his wife Mumtaz-i-Mahal (Huffine and Grau, 1969). The natural grass surface has also played an important part in the development of many sporting and recreational pursuits. Chaugau or polo frequently occupied the day for Akbar, 1556–1605 AD, the Great Emperor of Hindustan. The Plains Indians of the United States played baggataway, an early form of lacrosse, on the grassed prairies, either on foot or on horseback. The shepherds of early England and Europe played many competitive ‘ball and stick’ games while tending their flocks on the lowlands. The native population of many countries threw clubs at discs bowled along the ground, and played sport with balls and stones.

However it was during the years of the Crusades (11 to 13th centuries) that we see an increasing exchange of ideas as Europe came into closer contact with the East. By the 13 to 15th centuries, grassed areas were considered an integral element in the classical gardens of medieval Europe and Britain. The English dramatist and poet, William Shakespeare (1564–1616), makes reference to grass in his play The Tempest, (Act ii., sc.l.); ‘How lush and green the grass looks… Here, on the grass-plot, in this very place, to come and sport…’. Balthazar Nebot’s series of paintings of Hartwell House, in Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom (circa. 1738), depicts gardeners with scythes and lawn rollers (Sanecki, 1997). Other literary sources include the works of Miss Eleanour Sinclair Rohde who paid tribute to grass in ‘Nineteenth Century and After’, 1928, CIV, 200 (Dawson, 1949). In the 1930s, Englishman John Evelyn ’s instruction manual states that ‘bowling greens are to be mowed and rolled every fifteen days’ (Evelyn, 1932).

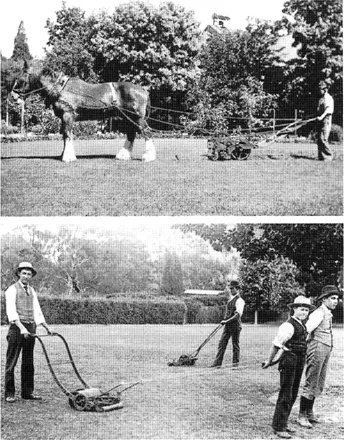

With the advance of the Industrial Revolution, there developed an increasing demand for goods, and gardening and sport became major leisure occupations for many of the new middle and upper class town dwellers. This stimulated the manufacture of implements and machinery for maintaining the garden. Eighteen-century lawns were originally grazed or cut with the scythe. In 1830 Englishman, Edwin Budding, an engineer at a textile mill, developed a cylinder or reel type mower, which consisted of a series of blades arranged around a cylinder with a push handle. The licence to manufacture this first lawnmower, based on Budding’s design, was granted in 1832 to Ransome of Ipswich in England, although a prototype had been made as early as 1831 by another Englishman named Farrabee. In 1841 Alexander Shanks of Arbroath, Scotland, had registered a pony-drawn mower which also swept up the clippings. By 1870 Elwood McGuire of Richmond, Indiana, had also designed a machine that mowed turf. With these inventions the hand scythe and cradles were abandoned for horse-drawn machines, and the sickle-bar mower was brought from the hay field to mow larger turf areas of parkland and land put aside for golf courses.

Prior to 1700 all seed was hand sown. Around 1701 Jethro Tull (1674–1741), an English agriculturist and inventor, perfected the seed drill. The introduction of fencing wire in 1840 enabled animals to be inexpensively confined close to grazed areas, and the advent of galvanised wire in 1851 and barbed wire in 1860 improved this situation. Post-World War n saw Power Specialists of Slough, England, introduce a rotary Rotoscythe mower which offered both petroldriven and electric models (Sanecki, 1997). In 1948 Australia entered the machinery market with the introduction of a petrol-driven Rotoscythe mower which was sold for 76 pounds, four shillings and sixpence by the Finally Brothers Pty Ltd of Melbourne. This was followed in the 1950s by the introduction of the first two-stroke rotary lawnmower by Australian designer and builder Mervyn Victor Richardson of Concord, New South Wales. By 1966 lightweight electric mowers were being developed and introduced by Flymo Ltd of Middlesbrough, England. Traction power for turf maintenance operations had progressed from draught animals (Figure 1.1(a)), or even students (Figure 1.1(b)), through steam-driven tractors to those with petrol or oil engines. Over the 1920s and 1930s there was a general tendency to abandon the horse in favor of the tractor-mounted mower, not only for constructional work, but also for regular mowing of large areas.

Figure 1.1 (a) Horse-drawn cylinder mower, circa 1941; (b) Student-powered cylinder mower, circa 1890 (Photos courtesy of Burnley Archives, University of Melbourne, Burnley College, Victoria)

History of significant turfgrass sports

Lawn tennis is thought to have evolved from the indoor game of real tennis, the word being derived from a corruption of the French tenez meaning attention or hold. Others make mention of the term jeu de paume or the palm game. Lawn tennis was played in monasteries in France as early as the 11th century. The long- handled racket was not invented until about 1500. ‘Field’ tennis is mentioned as early as 1793 in a British magazine. The first lawn tennis club was established in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, UK in 1872. The United States Lawn Tennis Association was formed in 1881, and the English equivalent, seven years later. The Wimbledon Championships were instituted in 1877, the US Open in 1881, and the Australian Championships in 1905. In Australia the first tennis match was played on an asphalt court laid at the Melbourne Cricket Club in 1878. The Club put down a grass court the following year. The Lawn Tennis Association of Australasia was formed in Sydney in 1904.

Lawn bowls originated with the crowned heads of Europe. During the reign of England’s kings, Edward III, Richard II and Henry VII, bowls was banned as a sport because the archers were often distracted by the game, thereby endangering the sustainabllity of the reserve military forces. Despite these legal restrictions, the game prospered with the world’s first bowling club established as the South Hampton Town Bowling Club in 1299. It Is reputed that the game of bowls was made famous by the English sea captain Sir Francis Drake (1540–96) who insisted he finish his game before his ships sailed to defeat the Spanish Armada in 1588. Lawn bowls has been played in Scotland since the 16th century. The modern rules were framed In Scotland by William Mitchell in 1848-9. The game is played mostly In the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth countries. Bowls came to Australia with the first migrants, who often established greens next to their bars and taverns, as was the custom. Australian research suggests that the earliest bowling greens were built at Sandy Bay in Tasmania, and the ‘Golden Fleece’ and ‘Woolpack’ hotels in Petersham, Sydney, as early as 1826. Victoria’s first bowling green was commenced in late 1845 by a Mr W. Turner who aptly named his premises the ‘Bowling Green Hotel’ (Gerty 1996). The first bowling ass...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction to turfgrass science and management

- Chapter 2 Turfgrass Identification and Selection

- Chapter 3 Turfgrass growth and physiology

- Chapter 4 Turfgrass soils and drainage

- Chapter 5 Turfgrass establishment, revegetation and renovation

- Chapter 6 Turfgrass construction materials and methods

- Chapter 7 Turfgrass irrigation

- Chapter 8 Turfgrass nutrition and fertilisers

- Chapter 9 Turfgrass machinery and equipment operation

- Chapter 10 Turfgrass plant health and protection

- Chapter 11 Turfgrass facility business and administration

- Chapter 12 Contract establishment

- Chapter 13 Contract management

- Chapter 14 The playing quality of turfgrass sports surfaces

- Chapter 15 Prescription surface development: Golf course management

- Chapter 16 Prescription surface development: Lawn bowling greens, croquet lawns and tennis courts

- Chapter 17 Prescription surface development: Sportsfield and arena management

- Chapter 18 Prescription surface development: Racetrack management

- Chapter 19 Prescription surface development: Cricket wicket management

- Chapter 20 Environmental issues in turf management

- Index