- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mountain Environments

About this book

This book breaks the ground in Geographical texts by transcending a strictly regional or topical focus. It presents the opportunities and constraints that mountains and their resources offer to local and global populations; the impacts of environmental and economic change, development and globalisation on mountain environments. Part of the Ecogeography series edited by Richard Hugget

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Evolution of mountain landscapes

Introduction: stability and instability

Mountains are well known as regions of extreme climate and hazardous conditions. Recent publicity over deforestation, degradation and the apparent imminent collapse of productive environments needs to be placed in the context of natural processes of formation and modification and the geomorphological, climatic and ecological environment. These three elements of the physical environment (Chapters 1–3) form a framework for considering resource availability and utilization (Chapters 7–9), and to some extent shape the culture and social organization of mountain communities (Chapters 4–6).

Physical processes of mountain regions are characterized by cyclicity and oscillations between stability and instability. Cycles of events may be diurnal, as in the aseasonal tropics where the greatest variation in environmental conditions occurs between day and night; seasonal variations occur in the temperate and high latitudes, whilst cycles of events such as drought or floods may occur on annual, decadal or much longer timescales of thousands of years, as for the Quaternary glacial-interglacial cycles, and on geological timescales of millions of years, as with the formation of mountains themselves. All these different cycles are superimposed and the complexity of resultant processes gives rise to diverse environments where small differences in slope angle, aspect or altitude can have great impacts on soils, vegetation, erosion and potential for land use. High-magnitude, low-frequency events such as tectonic uplift, earthquakes, major floods and glacial activity may occur at widely spaced intervals, resulting in periods of intense geomorphic activity (instability) and intervening periods of relative quiescence (stability). This creates a sort of ‘punctuated dynamism’ in landscape evolution, operating at a variety of timescales.

The concept of stability applies to the physical stability of landscapes, and also to their ecology (Gigon, 1983) and to the agricultural systems in operation (Winiger, 1983). The issue of stability and instability of mountain regions and their sensitivity and vulnerability to external forces of change, such as climate, has generated considerable academic interest. The landscape of mountains, with its high relative relief, large areas of bare rocky slopes, and abundant loose material means they are highly susceptible to erosion, especially under extreme climatic conditions – such as snow melt and heavy rainfall. Add to this the frequency of earthquakes and volcanic activity arising from their location in tectonically active areas, and it is easy to recognize the inherent instability of mountain environments. Whilst human activity has been blamed for enhancing natural rates of degradation, it is often the case that the management strategies of indigenous populations are able to cope admirably and effectively with the hazards of mountain living; this is explored further in Part 3.

The stability of a landscape is determined by its resistance and response to external forces of change (Allison and Thomas, 1993; Brunsden, 1993). The resistance comes from the geological character of the landscape – the rigidity, complexity and morphology of different rock types and structures, relief and elevation. The environment is able to absorb the effects of change by dissipating energy; for example, the deposition of sediment by a river as it enters a lake, or the dissipation of wave energy on a beach. In mountains, however, where steep slopes predominate, processes such as streamflow have an exceptionally high potential energy which is able to erode rapidly and to carry considerable quantities of material. Thus, mountain environments tend to be highly dynamic landscapes. The environmental history of mountains is also important – for instance, the legacy of past earth movements and the Quaternary glaciations mean that the geomorphology is always out of equilibrium, which contributes to their instability and propensity for change.

Our perception of how stable or unstable a mountain region is, is complicated by the fact that several different forms of stability exist. They describe different types of response according to the magnitude of the force of change and the response of the environment and its ability to absorb the change. Stability may be cyclic, such as the seasonal or diurnal temperature changes or variations in streamflow, or it may be elastic, reflecting a temporary change in response to a one-off event (an earthquake or a pollution event), with an eventual return to the original state (Gigon, 1983). Alternatively, the conditions may be constant, reflecting little change over time where the environment is able to absorb the effects of change without having to respond. All these different states and conditions may be superimposed at any one time, and the same factors may generate different responses in different areas (for example, the different responses of vegetation to global warming). The scale of observation in time or space also affects our perception of stability. What is important about mountains is that, although the actual processes operating are no different from those in any other environment, it is the influence of altitude in particular which gives them an image of enhanced activity and hazard.

Chapter 1

The making and shaping of mountains

Mountain building commonly occurs in three stages. First, a tectonic event such as uplift or volcanic activity creates elevated relief. Second, erosion processes reduce this elevation, whilst continued uplift may both counteract and enhance this. In the third phase erosion dominates and the net result is a gradual lowering of elevations. Thus, early geomorphologist' perception of mountains was as ephemeral landforms (Powell, 1895) with a ‘lifecycle’. The tectonic and erosion forces interact. Recent work (Pinter and Brandon, 1997) emphasizes the importance of erosion operating both in destructive modes by removing material, and in constructive modes by instigating uplift. Crustal adjustment to the removal of material by denudation or by deglaciation causes rebound of the crust (isostasy) and thus rejuvenation of the denudation processes. This recognition of the creative role of erosion views mountains as active, continually rejuvenated landforms. The uplift of land masses to form mountains interferes with atmospheric circulation and thus modifies climate on continental scales (Chapter 2). The interaction of tectonic, geomorphologic and climatic forces in creating and shaping mountains creates a series of positive and negative feedback effects, giving a degree of internal control. For example, the uplift of the Himalayas limits the effects of the monsoon to the southern parts of the range, whilst the rainshadow effect causes much drier conditions on the Tibetan Plateau, with the result that it is considerably less dissected than the southern Himalayan slopes.

Formation

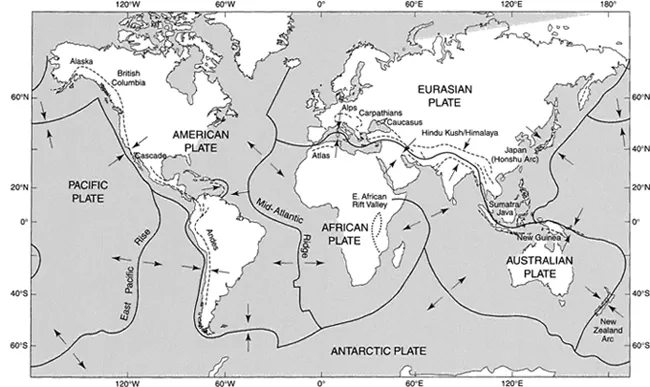

Mountains are formed primarily as a result of tectonic plate movements: the collision of plates causes compression and uplift of intervening sediments together with the subduction of one plate and associated volcanic activity (Figure 1.1). They may also form at divergent plate boundaries due to the upwelling of magma through the weakened crust – as in the case of the mid-Atlantic ridge which extends some 15 000 km and rises up to 4000 m above the ocean floor. Mountain building results in complex geological formations, with intense folding and faulting, intrusion of igneous material, metamorphic activity and consequently a varied lithology. The association of mountain building with plate boundaries, many of which are actively moving today, accounts for the frequent earthquake and volcanic activity and the sharp relief with which they are associated (Figure 1.2).

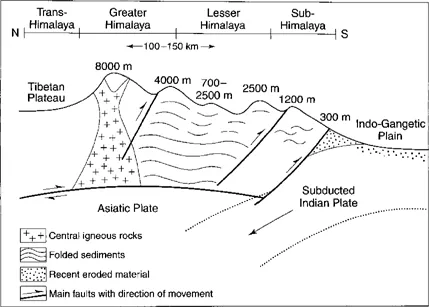

Figure 1.1 Simplified N–S section of the Himalayas showing the subducted Indian plate, and folding and faulting of the intervening sediments to form the mountains.

There is a perception that there has been enhanced tectonic activity over the last 40 million years, together with a phase of major climatic change during which the cycles of glacial and interglacial conditions prevailed (Isaacs, 1992). The link between the uplift of mountains and climatic change resulting from altered patterns of atmospheric circulation is well established but it is difficult to determine which ‘came first’. Continental drift can induce climate change by a change in the distribution of land and sea, and climate change could induce mountain building by enhancing erosion rates and thus uplift.

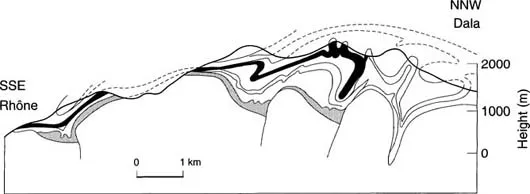

Fold mountains are formed by tectonic forces bending and shaping the earth's crust (Figure 1.3). They technically occur where the axes of the folds are generally parallel to the range, but faulting and cross-folds introduce complexity into the system and result in a diversity of outcrops and thus variable erodibility. Different groups of rocks occur: flysch and molasse sediments are uplifted marine and continental sediments respectively. They are often soft sandstones and shales and may be rapidly eroded. Intensely folded strata form nappes – bent-over folds, which introduce crest weaknesses exploited by denudation processes. Block faulting creates uplifted (horst) and lowered (graben) blocks such as those of the uplifted Black Forest and Vosges and down-faulted Rhine valley of Europe. These areas are characterized by broad flat valleys and dissected upland plateaux.

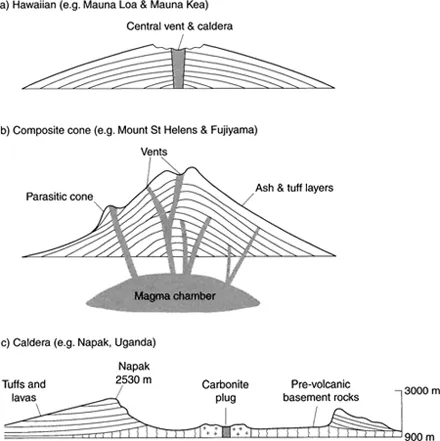

Volcanic mountains can be classified by the type of material and the nature of eruptive activity (Figure 1.4). Basalt cones produce runny lava and less explosive activity, forming gentle shield cones such as those of Hawaii. Vesuvian, Pelean and similar types are explosive and produce gas, ash and thick andesitic lava, forming steep, complex cones. Welded materials such as tuffs take longer to erode than uncemented ash and scoria. Most volcanoes have complex histories – Fujiyama in Japan actually comprises two more recent cones superimposed on a Pleistocene one. A buried soil between the oldest and the two younger cones indicates a period of quiescence lasting between 5000 and 10 000 years. Despite the activity of volcanoes, the rich, free-draining and fertile soils make them attractive places for human settlement.

Figure 1.2 Relationship between the main crustal plate boundaries and mountain ranges. The arrows represent the direction of plate movement (modified after White et al., 1992 and Strahler and Strahler, 1992).

Figure 1.3 Simplified SE–NW section of the Aar Massif in the European Alps, showing the complex folding and faulting of sediments which occurs in mountain building. Surface erosion exposes a variety of rock types at the surface, making these formations difficult to interpret. The dotted line marks the continuation of selected strata (after Baer, 1959).

Figure 1.4 Types of volcanic cone: a) Hawaiian cones have gentler slopes and form from runny lava with gentle eruptions, b) Composite cones with alternating ash and lava layers tend to be steeper and are associated with more explosive activity. c) Old volcano vents may collapse to form a caldera, leaving the rim upstanding as higher ground – this example is Napak, southern Uganda (adapted from King, 1949).

Box 1.1 The Himalayas

The Himalayas are complex and young, extending 2500 km northwest–southeast between north India and south Tibet with associated ranges of the Pamir, Karakoram, Hindu Kush complex extending north and west into Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the Zagros mountains of Iran. They join the mountains of Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean and also extend into Southeast Asia. They contain the world's highest mountain, Everest (8848 m), and many over 7000 m. The Himalayas were formed by the convergence of the Indian and Asian plates, beginning 40–50 million years ago. The intervening sediments were squeezed upwards as some 2 km of the Indian plate was subducted at rates of 150–200 mm/yr; since then t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Series preface

- Preface

- Publisher's acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 Evolution of mountain landscapes

- Part 2 Mountain people and cultures

- Part 3 Mountain resources and resource use

- Part 4 Managing mountains: development conservation and degradation

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mountain Environments by Romola Parish in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.