![]()

1

Introduction

Michele Meek

In January 1982, The Independent Film & Video Monthly featured a report from the second International Women Filmmakers Symposium at the Directors Guild of America (DGA) with the headline “Independent by Default—or by Choice.” Writer Marion Cajori states, “With very few exceptions, women had turned to independent production as a way out of long and frustrating years of work without being given any opportunity within the Hollywood system.” Yet, in the article, these same women filmmakers express that staying independent “offers more freedom and control over the quality of work, not to mention the possibility of actually practicing one’s craft.”

Therein lies the irony inherent in independent female filmmaking—it offers more “freedom” and creative “control,” but the path to be independent is not always explicitly chosen. Major Hollywood studios—who greenlight and fund most popular films—have been accused of “systematic discrimination” against women and people of color who pursue directorial roles.1 For the women filmmakers in this book, Independent Female Filmmakers: A Chronicle through Interviews, Profiles, and Manifestos, discrimination took various forms—Director Cheryl Dunye’s landmark NEA-funded film The Watermelon Woman (1996) was lambasted by Republicans in the US Congress for its depiction of lesbian sexuality; and Director and former DGA President Martha Coolidge recalls how she was told she could not obtain a producing credit (which not only meant more prestige but also more money) on some projects simply because she was a woman. Many of the women in this compilation turned to television to continue earning their living as directors and writers, and several—some by choice and others by necessity—became authors, teachers, or professors while pursuing their directorial careers.

Institutional bias has had a direct impact on the budgets, genres, and scales of the projects that women direct, as evidenced by the interviews in this collection. When asked in her 1981 Independent interview (republished in this compilation) what she might do with more resources, filmmaker Ericka Beckman responds, “It’s impossible to say now, because the ideas are now coming up reduced, so the time seems to have passed.”2 Similarly, in a discussion of why independent female filmmakers stay independent or move to television, Coolidge states, “you’re not offered [projects] like men.”3 Many women in this collection articulate that funding challenges kept them from directing features more steadily. Director Maria Maggenti states that it took her six years to fund her second film even after the success of her debut feature The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love (1995). When women do make films, they also seem to be held to higher standards—several women in this compilation mention how hard it is for women to “fail.” Maggenti states, “a woman who doesn’t succeed at every attempt that she is making is rarely given another chance,”4 while for men, as Coolidge states, just one success “would carry them through more okay movies. And, you know, another successful movie and that man would have a career.”5 When asked how racism and sexism affect her work, Filmmaker Julie Dash replies, “Simply by limiting the options available to me for the completion of my projects.”6

By this point, the statistics of women in media are well documented and widely reported—thanks to the studies overseen by Dr. Martha Lauzen and the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, Dr. Stacy Smith and the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at USC Annenberg, and the Geena Davis Institute. Their studies have demonstrated the paltry numbers of women both behind and in front of the camera. For example, Dr. Smith found that although women comprised nearly a third of the directors of short films featured at the top 10 worldwide film festivals in 2010–2014, their numbers drop substantially for features7—women directed only four percent of the top-grossing movies from 2007 to 2017.8 Such numbers are equally troubling for people of color—of the 1,100 popular films in 2007–2017, only five percent of directors were Black and only three percent were Asian or Asian American.

These numbers are disturbing, and they have not changed much in the past several decades. Dr. Lauzen directs annual studies to measure the rates of women directors, writers, producers, editors, and cinematographers in both the top 500 grossing films as well as in the independent film industry. In her historical comparisons, she found that the number of women directors of independent features screened at major film festivals changed from 24 percent in 2008–2009 to 29 percent in 2017–2018.9 In looking at Hollywood, Dr. Lauzen found that women directed only 18 percent of the top 250 grossing films, a statistic that has changed by only one percentage point in nearly two decades since 1998.10

Despite overwhelming odds against women’s making movies, many have persisted, as demonstrated by this compilation. But as the wide-ranging impact of sexual harassment and gender and race imbalance in the industry comes to light,11 we must ask ourselves—how many of these and other equally talented female filmmakers might have become as secured in their positions in the filmmaking canon as their male counterparts if it weren’t for unchecked biases? As Filmmaker Lizzie Borden states in her interview, “I’ve seen amazing films by women around the world while traveling with Born in Flames and realized that nobody will see or even count them.”12

Writer Lili Loofbourow in her article “The Male Glance” in the Virginia Quarterly Review details how film and television critics view and analyze male versus female work, arguing that the “male glance” is “the narrative corollary to the male gaze”—the way media made by or about men/boys receives more attention and praise than media made by or about women/girls. She argues, “The effects are poisonous and cumulative and have resulted in an absolutely massive talent drain. We’ve been hemorrhaging great work for decades, partly because we were so bad at seeing it.”13 Maggenti, in her interview for this compilation, states how Loofbourow’s essay resonated as “significant” to her, because, as she says,

I recognized so profoundly the ways in which women who work in the art of storytelling are not paid attention to, and when you’re not paid attention to and when you’re not taken seriously, it is harder and harder to get your work done.14

In other words, it is not only Hollywood who should be called out for discriminating against female filmmakers.

At the time of this writing, the University of Mississippi Press’s Conversations with Filmmakers series features books of interviews with 108 filmmakers—only seven of whom are women.15 So not only have female filmmakers faced intense discrimination throughout their careers, but they also then continue to meet such obstacles in how their work is received and remembered—even by academic publishers. I believe that, as scholars and critics, we must de-emphasize “auteur” film-making, as traditionally represented by a collection of feature films. Many of the women featured in this compilation have had what one might call “eclectic” film careers spanning genres, lengths, and forms—documentary, narrative, “experimental,” features, shorts, television, and web series. Their careers often include long gaps or several for-hire projects in between their own creative projects. Although today’s market for television offers some women greater funding opportunities and creative control, it still does not come with the cachet of feature film directing. I see no reason to continue such a misperception of their work. If we think that these women filmmakers have worked “in the margins,” it is we who have kept them there.

I believe it is on us as scholars, writers, teachers, and film fans, to contemplate, teach, write about, and promote the indisputable legacy of these women’s films. Otherwise, we are further perpetuating deep-seated industry sexism and racism. These women’s films, in other words, should be on our syllabi. They should be included in our research. Their films should be screened in our festivals and events. Their “lesser known” works should be distributed and widely available. Books and biographies should be written about them and with them. These women should be invited to speak at our universities and organizations, and they should be fairly compensated to do so.

In addition to highlighting women filmmakers, my aim in putting together this compilation is to highlight the archives of The Independent Film & Video Monthly. As a print publication from 1976 to 2006 and continued since then as an online publication at www.independent-magazine.org, The Independent has often focused on the alternative, activist, and grassroots filmmaker. Over the years, the publication has been instrumental in drawing attention to independent film—and it gave voice to filmmakers like Coolidge, Rainer, and Minh-ha and prominent scholars like Judith Halberstam and Laura Marks early in their careers.

As a filmmaker, film entrepreneur, and film journalist in the late 1990s, I became a regular reader of The Independent Film & Video Monthly and then later a more active participant—an “Online Independents” article in the May 1998 issue highlighted my company NewEnglandFilm.com; I wrote for the magazine in the 2000s; and I was elected to the Board of its parent organization, the Association of Independent Video & Filmmakers (AIVF) where I served from 2004 to 2005. As you can read more about in Erin Trahan’s chapter in this collection about the history of The Independent, in 2007, I formed a team to launch a new 501(c)(3) called Independent Media Publications when the AIVF folded, in order to acquire and preserve the archives of the magazine and continue its publication online. The print archives of The Independent, I knew then as I know now, constitute an absolutely integral historical record of independent filmmaking from the 1970s to the early 2000s. I encourage you to explore and reference those archives yourself at http://independent-magazine.org/archives/ thanks to our partnership with University of Massachusetts, Amherst Libraries and the Internet Archive.

Despite its focus on marginalized filmmaking, I discovered in preparing this book that The Independent’s coverage still concentrated largely on white, male filmmakers, and women filmmakers were often periodically grouped together in shorter profile pieces.16 Quite embarrassingly, I discovered that when The Independent interviewed me in 2002 about Boston-area filmmaking, I too highlighted only examples of white, male directors—Brad Anderson, David Mamet, and the Farrelly brothers. As perhaps with any publication, a look back through its archives presents some astonishing omissions—there were no long interviews with or profiles of some of the most indisputably important independent female filmmakers in recent history, such as Ava Marie DuVernay, Sophia Coppola, or Kimberly Peirce, among others.

Nonetheless, the list of trailblazing female filmmakers who were featured by The Independent is abundant and still represents too many to fit into a book-length project. In order to retain as much of a first-person perspective of the filmmakers as possible, I narrowed the list to filmmakers who had either a longer Q&A interview or their own first-person essay in the original publication, which left out filmmakers like Debra Granik, Allison Anders, Lynne Sachs, and others. Focusing solely on female directors also caused me to omit noteworthy women producers like Effie Brown and cinematographers like Jessie Maple. This compilation also features exclusively filmmakers working within North America, which omitted numerous European filmmakers who might (and perhaps will in the future) fill their own compilation, such as Monika Treut, Christine Van Assche, Emma Hed-ditch, and Margarethe von Trotta, to name a few. Nonetheless, the women film-makers featured here include a diverse range of ethnicities and nationalities, and many of them produced films outside North America—such as Minh-ha, Fox, and Mehta—in addition to maintaining their deep connections to North American cinema. Finally, two filmmakers—Karyn Kusama and Mira Nair—were ultimately omitted because we were unable to reach them (despite calls and emails to agents

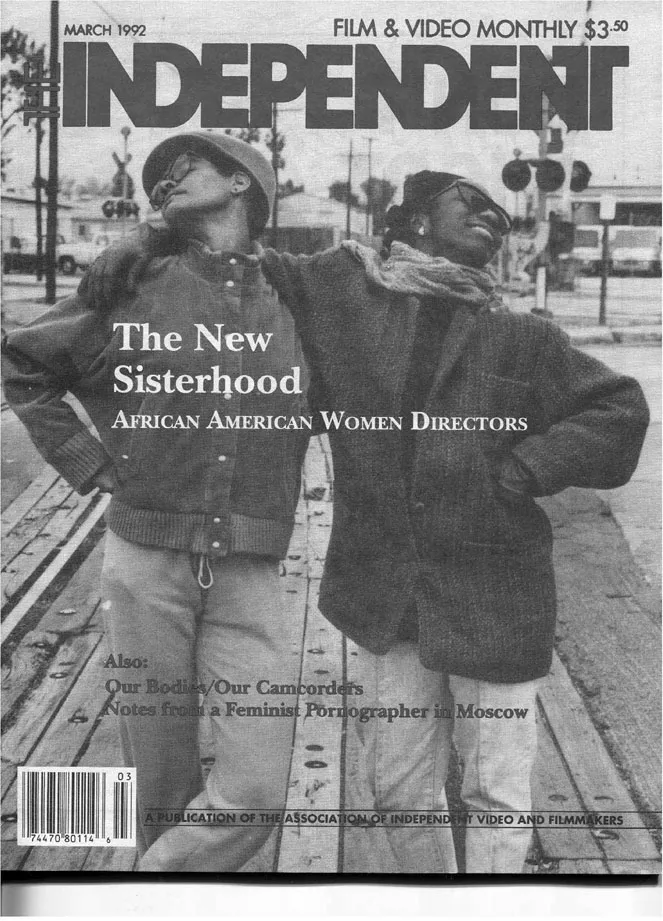

Figure 1.1 Cover stories in The Independent at times grouped women filmmakers together.

and managers) to conduct a current interview. However, I did retain the chapter on Julie Dash despite our inability to reach her as well.17

Of course, to suggest that the curation of this book was solely objective would be untrue. Rather, my goal was to assemble a group of women filmmakers whose work was not only influential at the time, but also continues to resonate today. The women in this compilation in many ways make unlikely companions—Coolidge’s ...