- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This text focuses on two major issues: the nature of scientific inquiry and the relations between scientific disciplines. Designed to introduce the basic issues and concepts in the philosophy of science, Bechtel writes for an audience with little or no philosophical background.

The first part of the book explores the legacy of Logical Positivism and the subsequent post-Positivistic developments in the philosophy of science. The second section examines arguments for and against using a model of theory reduction to integrate scientific disciplines. The book concludes with a chapter describing non-reductionist approaches for relating scientific disciplines using psycholinguistic and cognitive neuroscience models.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philosophy of Science by William Bechtel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Locus of Philosophy of Science

Introduction: What is Philosophy of Science?

This volume is devoted to introducing some of the basic issues in philosophy of science to the practitioners of the various disciplines of cognitive science: cognitive psychology, artificial intelligence, cognitive neuroscience, theoretical linguistics, and cognitive anthropology. Philosophy of science is a field devoted to analyzing the character of scientific investigations. It attempts to answer such questions as: What is a scientific explanation? To what extent can scientific claims ever be justified or shown to be false? How do scientific theories change over time? What relations hold between old and new theories? What relations hold, or should hold, between theoretical claims developed in different fields of scientific investigation? A variety of answers that philosophers have offered to these and other questions are examined in subsequent chapters of this book. Before turning to the concrete views philosophers have offered, however, it is useful to put the attempts to address these questions in perspective.

Since antiquity, philosophers have been interested in science for the reason that science seems to represent the most rigorous attempt by humans to acquire knowledge. This has led a number of philosophers to seek a criterion by which they could distinguish scientific endeavors and the resulting knowledge claims from other knowledge claims humans have advanced (e.g., ones based on mysticism, intuition). Philosophers, however, have not been the only people who have been fascinated by science and who have attempted to explain how it works. Historians have long been interested in the development of science, partly as an area of intellectual history. More recently, social historians and sociologists have focused on science and the social context in which scientific investigation occurs. There have even been a few investigations by psychologists directed at the scientific endeavor itself. Although there have often been bitter controversies between philosophers, historians, sociologists, and psychologists of science as to which discipline's methodology provides the best tool to explicate the nature of science, there is beginning to emerge a cluster of practitioners from a variety of disciplines who take science as their subject matter. Increasingly, the term science of science is being used to characterize these investigations.

As the term science of science suggests, the inquiry into the nature of science, whether carried out by philosophers or others, is a reflexive endeavor, using the very skills that are employed in human inquiry to understand the human race's most systematic example of inquiry—science. This reflexive inquiry, especially as done by philosophers, has had profound consequences on science itself. Many scientists have been seriously concerned with the issues of philosophy of science. Such concern is particularly likely to be expressed in the context of open debates within the scientific community when questions arise as to proper scientific strategy or legitimate style of scientific explanation. (The recent history of psychology has witnessed such controversies in the battles between behaviorism and cognitivism, whereas cognitive science generally is currently witnessing such a battle between connectionists and those advocating rules and representations accounts of mind.) Some scientists who become concerned about philosophy of science issues may become contributors to the literature in philosophy of science (e.g., Polanyi, 1958). Most scientists, however, simply adopt a philosophy of science that is popular, or that suits their purposes, and cite it as authority. This proclivity to borrow positions from philosophy is rather common but poses serious dangers because what may be quite controversial in philosophy may be accepted by a particular scientist or group of scientists without recognizing its controversial character.1 One of the objectives of this volume is to attempt to alleviate this situation in cognitive science by providing a brief, introductory account of the various competing philosophical perspectives on the nature of science. Then, if readers adopt a particular view of what science is, they will do so with some awareness of the alternatives and of some of the controversies that surround the position.

There are no sharp boundaries that divide the analyses of science advanced by philosophers from those offered by historians, sociologists, or psychologists. In general, however, philosophers have tended to be more interested than practitioners of these other disciplines in the reasoning processes actually or ideally employed by scientists and have sought to identify criteria that give scientific claims their objective validity. Moreover, philosophers bring to their analyses of science a background that involved training in other areas of philosophy. As a result, they often call upon the conceptual tools developed in other areas of philosophy in analyzing science.2 To provide nonprofessional philosophers the necessary background to understand and appreciate the claims made by philosophers of science, the remainder of this chapter is devoted to providing a brief introduction to other areas of philosophy that bear upon philosophy of science.

Areas of Philosophy that Bear on Philosophy of Science

Philosophy as practiced in the modern Western world is probably best characterized as an attempt to develop systematic and defensible answers to such questions as: What are proper modes of reasoning? What are the fundamental categories of things? How can humans know about the natural world? How should humans behave? These questions define the basic domains of philosophy—logic, metaphysics, epistemology, and value theory. All of these bear to some degree on philosophy of science. The following is a brief account of the basic issues in each of these domains and of how these issues impact on philosophy of science.

Logic

The central issue in logic is the evaluation of argument. An argument is simply a set of statements, some of which serve as premises or support for others, that are called conclusions. Two criteria are relevant to evaluating arguments: Is the argument of such a sort that if the premises were true, the conclusion would also have to be true? and Are the premises true? An argument that satisfies the first of these criteria is traditionally called valid whereas an argument that satisfies both is called sound. The discipline of logic is primarily concerned with the first of these criteria, that is, with determining whether the argument is of a sort where the truth of the premises guarantees the truth of the conclusion. The truth preserving ability of an argument turns out not to depend on the content of what is stated in the argument but only on the form of the argument. The concept of argument form can be explicated intuitively as that which remains when all the words or phrases bearing content have been replaced by variables, provided that the same substitution is made for all instances of words or phrases that have the same content. (For example the logical form of the sentence "It is raining and it is cold" might be "x and y," where x and y are variables.)

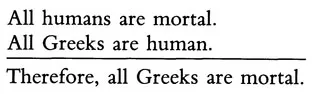

There have been two basic accounts of logical form in the history of philosophy. One goes back to Aristotle and gives rise to what is called syllogistic logic. The second was developed in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, principally through the work of Frege and Russell, and constitutes what is commonly referred to as symbolic logic. Syllogistic logic can be construed as a logic of classes, and uses information about what class an object belongs to or information about class inclusion to determine other relationships. The basic form of reasoning employed is the syllogism in which two statements about membership relations between objects and classes of objects are used to support an additional statement. The following is a typical valid syllogism:

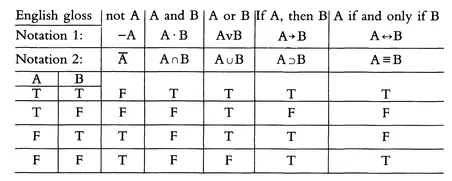

Although syllogistic logic proved useful for capturing a variety of vahd forms for arguments, there were a significant number of arguments that could not be captured. Modern symbolic logic was developed in order to overcome this shortcoming. There are two components of symbolic logic. The first is commonly spoken of as sentential logic or propositional logic, and the second is called quantificational logic or predicate calculus. Sentential logic takes simple complete sentences or propositions such as "it is raining" as units. It then uses truth functional connectives to build more complex, compound sentences. A connective is truth functional if the truth or falsity (truth value) of the compound sentence can be ascertained just by knowing the connective employed and the truth value of the component sentences. Although the connectives of sentential logic are defined in terms of precise rules that deviate from those governing the corresponding English words, the main connectives are generally expressed using the words "not," "and," "or," "if ———, then ...," and "if and only if." Through a device known as a truth table, one can show how the truth values of various compound sentences depend on those of the component sentences (represented by the letters A and B). The truth value of a sentence is indicated by placing a T or F in the appropriate place in the table. The truth tables for sentences formed using the basic connectives just listed are shown here (a common symbol for the connective is indicated below the English statement for the compound): The truth table for most of these connectives is just what one would expect. The troublesome one is the "if A, then B" connective, which is somewhat counterintuitively assigned the truth value true whenever A (the antecedent) is false. Part of the motivation for this interpretation can be captured by considering under what circumstances the statement could be recognized as false. The only such circumstance is where A is true and B (the consequent) is false. One important point to notice, though, is that given this interpretation of the "if———, then ..." connective, it is not proper to think of it as equivalent to implication. Logicians, rather, speak of it as the "material conditional."3

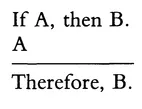

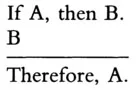

Derivations in sentential logic use premises and conclusions consisting of either simple statements or compound statements constructed from simple statements using these truth functional connectives. There are many such forms of valid derivations. One of the most important of these, known as modus ponens or "affirming the antecedent," is the following:

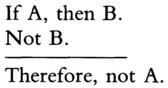

Another very important form, known as modus tollens or "denying the consequent," has the following form:

Treating these and some other basic forms as rules that license inferences from statements of the form of the two premises to statements of the form of the conclusion yields a system of natural deduction. In such a system you begin with a set of premises and apply a series of such rules to derive an ultimate conclusion.

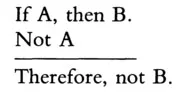

Of course, not all forms of argument are valid. There are, in fact, two invalid forms that closely resemble the valid forms above. The first, known as affirming the consequent, has the following form:

The second, known as denying the antecedent, has the form:

The forms can be recognized as invalid by substituting "it rains" for A and "the game will be cancelled" for B. Now assume in each case that the premises are true and consider whether the conclusion might be false. Because it clearly could be false, the argument form is not valid.

Quantificational logic expands on the power of sentential logic by exposing the inner structure of the basic statements used in sentential logic and showing how a variety of valid forms rely on this structure. The structure in question is the basic subject-predicate structure, as is found in the sentence "the sky is blue." To represent this structure, replace the subject terms (those referring to objects) with lower-case letters from the beginning of the alphabet and predicate terms with upper-case letters from the middle of the alphabet. Thus, the earlier sentence may be represented as "Pa," where P = "is blue" and a = "the sky." The predicate term in this case covers only one object, and so is termed monadic. It is also possible to have relational predicates that take two or more objects. For example, "taller than" is a relational predicate and the sentence "Carol is taller than Sarah" may be represented Tab.

In addition to representing statements referring to specific objects, quantificational logic allows for generalizations that assert either that a statement is true for any object or for at least one. Thus, the statement "All dogs have hearts" can be symbolized as (x)(Fx → Gx), Which is read "For all x, if x, is a dog, then x has a heart." Similarly, the statement "There exists a white dog" is symbolized as (∃x)(Fx · Gx), which is read "There exists an x such that x is white and x is a dog. In natural deduction systems for quantificational logic there are specific rules governing when it is permissible to introduce or remove these quantifiers. These rules give quantificational logic a power deductive structure. (For an introduction to symbolic logic and many issues concerning logic relevant to cognitive science, see McCawley, 1981.)

The interest in logic, however, goes beyond the ability to use it to produce detailed proofs. There are interesting properties that can be proven of logical systems themselves. Many of these proofs of what are called metatheorems were developed as part of an endeavor to use logic to provide a foundation to arithmetic. Frege, for example, set out to show that all the truths of mathematics could be rendered in terms of arithmetic and that all the principles of arithmetic could be rendered in terms of logic. (This project is known as the reduction of mathematics to arithmetic, and arithmetic to logic.) Frege had to abort his program when Russell pointed out a contradiction in the system Frege had developed. Logic requires consistent systems because if a system is inconsistent it is a trivial exercise to derive any statement from it. One of the basic things that must be established for any logical system, therefore, is that it is consistent. The demonstration that Frege's system for deriving arithmetic from logic was inconsistent undercut the interest in that system.

The program of reducing arithmetic to logic turned out to be impossible, but pursuit of this program resulted in number of important findings. For example, in addition to consistency another important property of a logical system is completeness. A complete system is one in which the axiom structure is sufficient to allow derivation of all true statements within the particular domain. Kurt Gödel established that quantificational logic is complete—any statement that must be true whenever the premises are true can, in principle, be derived using the standard inference rules for quantificational logic. But the fact that a system is complete does not mean that a procedure exists to generate a proof of any given logical consequence of the premises. If such a procedure exists the system is decidable. Sentential logic is decidable, and so are some restricted versions of quantificational logic. But Church proved that general quantificational logic is not decidable. In general quantificational logic, the mere fact that we have failed to derive a result from the postulates does not mean that it could not be derived; it may be that we simply have not yet constructed the right proof. Of even more significance to the program of grounding mathematics in logic was Gödel's proof that, unlike quantificational logic, there is no consistent axiomatization of arithmetic that is complete. This is referred to as the incompleteness of arithmetic and is commonly presented as the claim that for any axiomatization of arithmetic there will be a true statement that cannot be proven within the system. (For detailed treatments of these theorems, see Quine, 1972, and Mates, 1972.)

Some of these theorems about logic have played important roles in the development of computer science. Other claims of logic, which are commonly accepted as true but which are not or cannot be proven, have figured prominently in motivating the use of computers to study cognition. An example is Church's thesis, which holds that any decidable process is effectively decidable or computable, which is to say that it can be automated. If this thesis is true, then it follows that it is possible to implement a formal system on a computer that will generate the proof of any particular theorem that follows from the postulates. The assumption that this thesis is true has buttressed the use of computers in studies of cognitive processes. Assuming that cognition relies on decidable procedures, this thesis tells us that these procedures can be implemented on a digital computer as well as in the brain. (For a challenge to this assumption, see Smolensky, in press.) Symbolic logic has played a more general role in artificial intelligence. Many have assumed that the procedures of symbolic logic characterize much of human reasoning, and because these procedures can readily be implemented on a computer, many investigators have tried to develop simulations of human reasoning using computers equipped with these inference procedures. For our purposes here, however, the interest in logic is that numerous philosophers have tried to explicate scientific theories as logical structures and the structure of scientific explanations in terms of f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- PREFACE

- 1 THE LOCUS OF PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

- 2 LOGICAL POSITIVISM: THE RECEIVED VIEW IN PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

- 3 CHALLENGES TO LOGICAL POSITIVISM

- 4 POST-POSITIVIST PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

- 5 THEORY REDUCTION AS A MODEL FOR RELATING DISCIPLINES

- 6 AN ALTERNATIVE MODEL FOR INTEGRATING DISCIPLINES

- POSTSCRIPT

- REFERENCES

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX