- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Realms of Meaning presents an accessible introduction to semantics. It provides an understanding of the way meaning works in natural languages, against a background of how we communicate with language. Avoiding theoretical terminology and linguistic theories it concentrates instead on the analysis of meaning, and looks in depth at such subjects as opposites and negatives, modal verbs, prepositions and word meanings. Examples are chosen mainly from English to provide material for the wider discussion of the principles of the subject, but European, East Asian and other languages also provide illuminating examples.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Realms of Meaning by Thomas R. Hofmann,Thomas Hofmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

On Entering the Realms

How is it that I get ideas in my head when I hear sounds of my language, but not when I hear sounds of another language?

Humpty Dumpty said to Alice that he could make a word mean exactly what he wanted it to mean; that it was only a question of who was to be the master. Can you? Can he really?

It is no doubt more interesting to talk about the meanings of words and sentences than to try to talk about what meaning is. Nevertheless, it is worth a few words at least, to know where we are going and how to fit things together.

The English verb to mean can be used for many things: in just about any case where you can learn something important, F, from something else, X, we can say ‘X means F (to you)’. For example, if we can know that it is going to rain from some dark clouds blowing up, it is perfectly natural to say ‘Those clouds mean rain.’ The optional ‘(to you)’ is used in case you would conclude it but others might not.

what did she mean by winking like that?

that nasal accent means he comes from Chicago,

how she feels means a lot to me.

who do you mean to refer to by that?

who do you mean by ‘that guy with an earring’?

what does the word teacher mean?

what do you mean by freedom?

Really, however, we are not so interested in this particular word of English, even if philosophers worry a lot about it. As would-be scientists, we are interested rather in what the world of meaning in language is like, and freely accept that English words might not match that world too closely. The noun meaning is closer to our needs, for it cannot be used in all the ways the verb can.

Q. | Which of the ways that to mean was used above can be paraphrased (i.e. said in a different way) with the word meaning? The last, for example, can be paraphrased as ‘The meaning of (the word) freedom for me is . …’1 |

On a most basic level, the meaning that we are interested in is cognitive or descriptive meaning: what is communicated when one person tells another something. That is, we are interested in the meaning that can be expressed in language, meaning that describes something. There are also some other things that we can learn by listening to a person, like his social or geographical origins or his emotional state, that we should not want to call meaning. If we heard ‘Gimme a cup o’ wa’er’, we can guess a lot about its speaker – where he comes from as well as the fact that he is thirsty – but all that is hardly his meaning. He did not say he was from London, only that he wanted some water – and he might be an actor putting on a local style of speech. Happily, these other things are seldom subject to much control, so descriptive meaning can usually be distinguished as being easily controlled by all competent speakers. Of course, some people control it less well, but by learning more about it we can all control it better.

Q. | Is there any difference between saying, ‘She gave me, a man from York, a call’ and ‘She gave us a call’ in a male Yorkshire voice? If I were a New Yorker, would I be lying if I said these, pretending, or what?2 |

Language as a tool

Although we have excluded a lot of things from meaning, there is plenty left. Enough, in fact, to make this one of the most exciting areas in language to study; it is, I believe, much of what makes human beings human, and what allowed us to dominate all other animals so that now they work for us or entertain us. Each type of animal has some special weapon or defence, like running fast or sharp teeth, sharp ears, long claws or a long neck. We humans excel in none of these ways, but we have language.

How is language stronger than claws and teeth and speed? Simple: ten men armed with only stones or clubs can take a tiger or an elephant by surrounding it and coordinating their actions so that several attack its weak spots whenever it attacks one of them. Some animals like dogs or sheep use numbers as a weapon, but in coordinating ourselves we become like a single animal spread out in many different places! This was so effective that even thousands of years ago, the only wild animals that didn’t avoid human beings were dead animals.

It used to be said that what distinguished human beings was that they make and use tools. Unfortunately for our pride, however, some types of great apes have been seen to use tools, and even to invent simple ones, and some birds will also do so. Chimpanzee mothers have even been seen in the wild showing their offspring how to use things as tools – but how much can you learn by imitation? Some animals have communication systems, of course, but they are so limited in what they can communicate that linguists refuse to call them languages. The most extensive one known, that of some honey bees, can (apparently) communicate only a location – where some nectar is to be found. Our languages by contrast can communicate apparently anything – locations, emotions, facts, procedures, possibilities, fantasies, lies and many other things.

Q. | What is communicated in: a dog’s bark, whine, snarl? a cat’s meow, purr, …?3 |

There is no doubt that human beings are superior to most or all animals in being able to think, but what is thinking? A lot of our thinking is done in our native languages, sort of like talking to ourselves. If we can understand what meanings a language can express, we will be much closer to knowing what thinking is. In any case, it seems doubtful whether we might be any better than other primates in thinking without language.

Q. | Might there be something that human language cannot communicate? What? Please tell me about it, if you can.4 |

I am not even convinced that we can think much better than the great apes – you or I, that is. What tools have you invented recently? Our languages give us, almost from birth, the refined wisdom of our ancestors. Every useful procedure and tool has a name, and when we learn our first language we learn these names and what to apply them to. The words for concepts that do not prove so useful are normally forgotten in a generation or so.5 By going on from what our ancestors have learned we have left our primate cousins far behind, for each one of them has to start once again from the beginning. No doubt the chimps have had their geniuses, but their discoveries are always lost when they die.

Q. | When you take an elementary course in chemistry, or poetry, or any subject, a lot of your effort goes into learning the specialized vocabulary. What are you really learning?6 |

Communication

The sort of communication in which we are interested then, is that between two people, one making sounds with his or her mouth (or hand movements in sign language, or pencil marks in written language) and the other listening (or watching or reading). Of course it is not enough simply to make sounds, for if I said ‘nǐ dǒng bu-dǒng wǒ suǒ–shuō-de ì-si?’ or ‘est-ce que tu comprends tout ce que je dis?’ or ‘zenbu wakarimasu-ka’ or simply ‘tukusiviin’, you wouldn’t have any idea of what I was saying unless you knew some Chinese, French, Japanese and Eskimo respectively. We don’t have communication unless the receivers get ideas from the sounds.

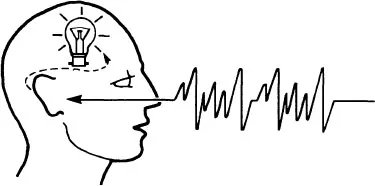

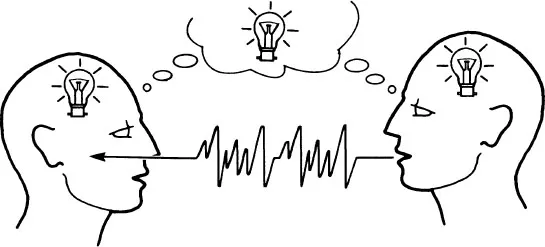

Even that is not enough; they must get the right ideas. If I pronounced the sound [hai] in the right way, they might think I was agreeing with them if they thought I was speaking Japanese or Cantonese Chinese, while I might only be greeting them in English. Or I might be saying ashes in Japanese or high in English. Unless they get the idea I want them to, we don’t have good communication. A simple diagram of this is in Fig. 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Diagram of ‘good communication’

Communication is successful if the idea they get (the impact on them) is the same as what I intended them to get (my intent). If they don’t match, then we have poor or no communication, and the idea-bulb in the cloud above their heads is dim or completely out. Poor communication is an interesting study in itself – it happens often enough – but it is wisely left until we know what happens in this ideal case of good (i.e. perfect) communication. The meaning that we will study, then, is whatever it is that gets transmitted between people in a case of good communication, i.e. when the intent and the impact are identical.

The study of meaning is exciting, and important, because it concerns the top half of the diagram – the brains of these two people, and the idea floating in the cloud above them. It has been slow to develop, as we don’t like cutting into people’s brains (don’t worry about yours; we shan’t touch it) and we can’t see ideas or record them for study as we can see lips and tongue, and record the sounds they form. In the last ten years or so we have made machines that can recognize language sounds nearly as well as our ears can do it. It seems unlikely that we shall ever make a machine, however, that can record the ideas, for ideas are not objects. While ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Semantic Elements and Other Symbols

- Chapter 1. On Entering the Realms

- Chapter 2. Markedness and Blocking

- Chapter 3. Opposites and Negatives

- Chapter 4. Deixis

- Chapter 5. Orientations

- Chapter 6. Modal Verbs

- Chapter 7. Time: Tense and Aspect

- Chapter 8. Limits to Events

- Chapter 9. Prepositions

- Chapter 10. Reference and Predication

- Chapter 11. Words to Sentences

- Chapter 12. Word Meanings

- Chapter 13. Combining Sentences

- Chapter 14. Meaning and Context

- Chapter 15. Afterwords

- Answers to Exercises

- Word/Topic Index