Introduction

I had originally intended to title this chapter ‘Human Presence’. After all live, human activity in music making is a central theme of this entire book. Yet as it emerged, it became apparent that this chapter was not so much about ‘live humans’ in music as about the relationship of the human music maker to other possible sound sources and agencies, whether natural and environmental or human-made and synthetic. Thus while I accord the human being a central position in a discussion of ‘living presence’, other entities will be identified and contribute to our sonic discourse. It might also have been called ‘Real World Presence’; but here, too, distinctions are hard to maintain – just what might a ‘non-real’ or ‘abstract’ world be like if it is in my imagination? This question presupposes an ‘observer-world’ distinction which I wish to play down in this text. My imagination is part of the living and real world. Nonetheless this ‘real-non-real’ distinction is very important historically. It is clear that there is a transcendental tradition in music which does indeed seek to ‘bracket out’ most of the direct relationships to what we might loosely call ‘real world’ referents. Pierre Schaeffer’s reaffirmation of the acousmatic and the particular way he established the practices of musique concrète continued this aesthetic line. The first part of the chapter examines this approach based on ‘reduced listening’ and – more importantly – some of the many and various rebellions against, and reactions to, its strictures. It seems that so many composers have wanted to bring recognizable sounds and contexts back into the centre of our attention that something more profound is at work. To explain this we need to step back from history for a moment to examine just what ‘cues and clues’ we are getting from the sound stream to allow us to construct what may be a recognizable ‘source and cause’ (whether human or not) for what we heard. And we will want to go even further – we may also react and respond to the sounds and search for relationships and meanings amongst the agencies we have constructed.

Presence – something is there. Of course when we hear something we can simply say ‘there was sound’. We can describe the sound literally using a wide variety of languages. There can be a scientific attempt to describe sound without reference to actual objects in the world around us – that is in terms of its measurable ‘abstract’ parameters, spectrum, noise components, amplitude envelopes and the like. But in contrast we have languages of description that use more metaphoric kinds of expression. These might draw parallels with other sense perceptions, colour, light and dark, weight and density, sweet and sour, speed and space, shape and size. We might, in time, learn to relate these two language domains. But description of the sound in these terms is not description of our experience of it. We might tentatively move in that direction – we might describe a sound as ‘threatening’, ‘reassuring’, ‘aggressive’ or even ‘beautiful’ but what we are doing is not so much to describe the sound as to describe our response to it. This response will be based on a complex negotiation of evolution and personal circumstance. It may be that we cannot completely suspend the ‘search engine’ that is our perception system (even when we sleep). This engine seeks to construct and interpret the environment (perhaps the two cannot be separated). Furthermore the perceiving body – the listener – is part of that environment and not a detached observer.

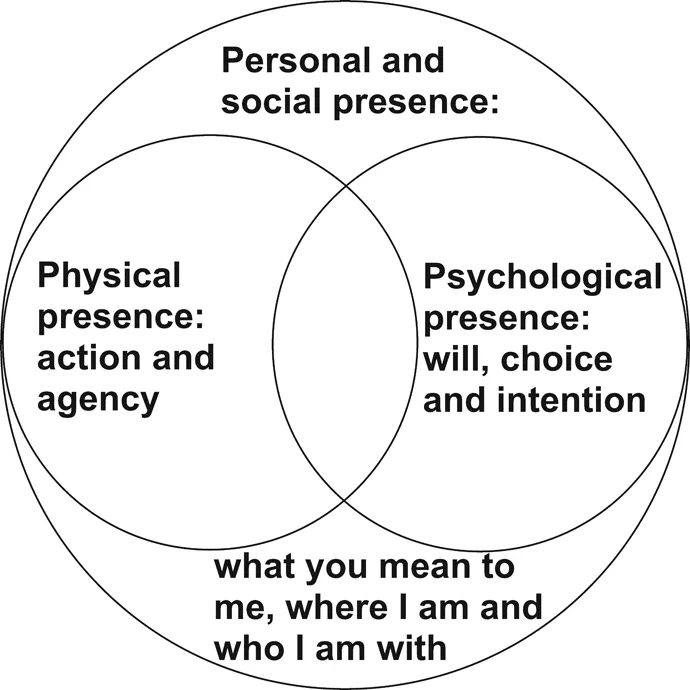

I intend to approach this ‘search and response’ in three parts – but these parts are not ‘stages’: I am forced to address one after the other but they are in practice simultaneous and interacting. First we discuss the search for Physical Presence: Action and Agency. The listener can gain basic information on objects, agencies and actions in the world, allowing a tentative construction of possible sources and causes of the sounding flow. But perception does not stop there. The search also applies to a different dimension. Playing games and constructing narratives, our listener also searches for clues on Psychological Presence: Will, Choice and Intention. What are the options, choices and strategies open to the (surmised) agencies in the ‘auditory scene’. What might happen next and are our expectations met? Furthermore both these two ‘presences’ are themselves embedded in a third: the listener is somewhere real – not outside the world. There is Personal and Social Presence. Where are you? Who are you with? What do they mean to you? How do you relate to them? I suggest that ‘style’ and genre are not simply descriptions of the sounding features but must include a discussion of venue, social milieu, performance and dissemination practice. A simple comparison of different genres of electronic and acousmatic music which have upset traditional definitions shows this clearly. The ‘identity of the work’ is not something fixed and unchanging if we compare ‘traditional’ acousmatic composition, laptop improvisation and ‘electronica/IDM’. We can summarize the core of this attempt at a holistic approach in a simple diagram (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Living presence

Can Listening be ‘Reduced’?: On not Recognizing Origins

An agent is an entity (a configuration of material, human, animal or environmental) which may execute an action (a change in something, usually involving a transfer of energy). We will be mostly concerned here with the causes of actions by agents which result in sound. In most music before recording the need to search for and identify the source of sounds was minimal if not non-existent. Occasionally musical results might be surprising (Haydn) or even terrifying (Berlioz) but the field of sound-producing agents for music was limited by conventional mechanical instrumentation. This itself was perpetually evolving and adapting to meet a complex of musical, social, economic and technological demands. Thus developments and additions were incremental, and could be seen, heard and understood relatively quickly.

Consider a piano concerto or symphony of the early twentieth century compared to one of about 1800. The immense additional volume of sound would be delivered from an iron-framed piano; violins, wind and brass which had been redesigned to be louder, more versatile and with extended range (tuba, bass trombone); possibly entirely new instruments (saxophone) and newly imported instruments (percussion).1 But all were recognizably from the same stables as their predecessors. A knowledgeable ear might pose and then hazard answers to questions of inventive orchestration. But this was not a necessary prerequisite for appreciation of the music – although when Wagner deliberately hid the orchestra in his design specification for the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, he clearly intended the mundanities of physical production to be ‘bracketed out’. Wagner suggests a kind of acousmatic listening to ‘absolute music’:

… I hope that a subsequent visit to the opera will have convinced [the reader] of my rightness in condemning the constant visibility of the mechanism for tone production as an aggressive nuisance. In my article on Beethoven I explained how fine performances of ideal works of music may make this evil imperceptible at last, through our eyesight being neutralized, as it were, by the rapt subversion of the whole sensorium (Wagner, 1977, p. 365).2

But aesthetic argument is complemented by acoustic consequence; luckily the two here reinforce:

Although according to all that Wagner published on the sunken pit the main purpose was visual concealment, it has the secondary effect of subduing the loudness and altering the timbre of the orchestra. The sound reaching the listener is entirely indirect (that is, reflected), and much of the upper frequency sound is lost. This gives the tone a mysterious, remote quality and also helps to avoid overpowering the singers with even the largest Wagnerian orchestra (Forsyth, 1985, p. 187).

Even when confronted by an entirely new instrumentation – the gamelan ensemble at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1889 for example – generic vocal, metallic or bowed string timbres could quickly be related to source. Western music has often appropriated these sources, which are always absorbed with an apparent amnesia, later to include the African xylophone and other percussion instruments from pre-Columbian cultures of the Americas.

But the ability to identify instrumental timbres was not really an issue – it was not part of the game of classical composition. The landscape of classical music (as Trevor Wishart has described it) is ‘humans playing instruments’. The ‘search engine’ of our perception system is only minimally engaged. However, the acousmatic condition that recording emphasized (but did not strictly invent) slowly reengaged this faculty as part of an aesthetic engagement with a new ‘sonic art’ not based on any agreed sound sources. But it did so in a way which was to produce tensions and contradictions within the music and amongst its practitioners. The unresolved question in short – do we want or need to know what causes the sound we hear?

Pierre Schaeffer’s answer is clearly ‘no’, and in developing the ideas of musique concrète, he placed this response at the centre of his philosophy, calling it écoute réduite (‘reduced listening’) which is encouraged by the acousmatic condition. As paraphrased by Michel Chion:

Acousmatic: … indicating a noise which is heard without seeing the causes from which it originates. … The acousmatic situation renews the way we hear. By isolating the sound from the “audiovisual complex” to which it initially belonged, it creates favourable conditions for a reduced listening which concentrates on the sound for its own sake, as sound object, independent of its causes or its meaning … (Chion, 1983, p. 18).

Not only (according to this view) was source identification (and any associated ‘meaning’) unnecessary, it was misleading, and distracted from the establishment of a potential musical discourse: carefully chosen objets sonores become objets musicaux through studio montage (their relationship to other sounds) guided by the listening ear. The necessary skills were developed in a thorough training combining research and practice (Schaeffer, 1966).

But there remains a niggling doubt about the premiss. Michel Chion (whose paraphrase of Schaeffer (quoted above) is that of a sympathetic insider, as a member of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (1971–76)) expresses it simply:

… Schaeffer thought the acousmatic situation could encourage reduced listening, in that it provokes one to separate oneself from causes or effects in favor of consciously attending to sonic textures, masses, and velocities. But, on the contrary, the opposite often occurs, at least at first, since the acousmatic situation intensifies causal listening in taking away the aid of sight (Chion, 1994, p. 32).

This doubt opens the door to a vast range of acousmatic musics, as we shall see.

Throughout the history of the post-renaissance western arts many revolutionary practitioners have appeared to set out to overthrow and replace a particular world view while in practice becoming part of a renewal process which would in time be absorbed into the mainstream.3 Yet, paradoxically, in some ways Pierre Schaeffer’s was a mirror position to this. His intention was to renew and revitalize from the inside, yet in many ways his work has turned out to be more revolutionary and universal in its consequences than he ever intended.

If one admits that it is necessary to be a musician to enjoy well the classics, that it is necessary to be a connoisseur to appreciate suitably jazz or exotic musics, then it is necessary to hope that the public will not claim entry at first attempt to the concrète domain. That is because this entry is so new, renewing so profoundly the phenomenon of musical communication or of contemplation, that it appeared to me necessary to write this book (Schaeffer, 1952, p. 199).

His attack on notation (in the sense of the manipulation of symbols) as the central means to produce music (which he called ‘musique abstraite’) and its replacement with sonic quality (the manipulation of sound as heard) as the driving force (‘musique concrète’) remains a monumental shift of focus. Yet it was intended to renew and revitalize the western tradition not replace it.

At heart his insistence on reduced listening means that musique concrète was intended to refine and...