![]()

1. Introduction

Key Messages

Climate change is a major global threat. Over the last century, global temperatures have risen by 0.7°C. Sea levels are rising at three millimetres a year and Arctic sea ice is melting at almost three per cent a decade. Continued warming of the atmosphere at the same rate will result in substantial damage to water resources, ecosystems and coastlines, as well as having an impact on food supplies and health.

The economic costs of climate change impacts have been estimated at between 5 and 20 per cent of global GDP and could be considerably higher.

Current evidence suggests that to avoid the worst effects of climate change we should aim to stabilise levels of atmospheric CO2e at 445-490 parts per million (ppm). Achieving this global stabilisation target will require strong and urgent international action.

The forest sector plays a key role in tackling climate change. Forestry, as defined by the IPCC, accounts for around 17 per cent of global GHG emissions – the third largest source of anthropogenic GHG emissions after energy supply and industrial activity. Forest emissions are comparable to the annual CO2 emissions of the US or China.

Analysis for this Review estimates that, in the absence of any mitigation efforts, emissions from the forest sector alone will increase atmospheric carbon stock by around 30ppm by 2100. Current atmospheric CO2e levels stand at 433ppm. Consequently, in order to stabilise atmospheric CO2e levels at a 445-490ppm target, forests will need to form a central part of any global climate change deal.

In addition to their role in tackling climate change, forests provide many other services. They are home to 350 million people, and over 90 per cent of those living on less than $1 per day depend to some extent on forests for their livelihoods. They provide fuelwood, medicinal plants, forest foods, shelter and many other services for communities.

Forests also provide additional ecosystem services, such as regulating regional rainfall and flood defence and supporting high levels of biodiversity. Maintaining resilient forest ecosystems could contribute not only to reduced emissions, but also to adaptation to future climate change.

The Bali Action Plan provides a roadmap for the negotiation of a new regulatory framework for international action on climate change, following the expiry of the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol in 2012. The action plan sets out key areas to be negotiated with a view to reaching a new global climate change deal in Copenhagen at the end of 2009. It recognises the importance of reducing deforestation emissions and a system of international finance to meet this goal.

The aim of this Review is to examine international financing to reduce forest loss and its associated impacts on climate change. The Review focuses particularly on the scale of finance required and on the mechanisms that can, if designed well, lead to effective reductions in forest carbon emissions to help meet a global stabilisation target. It also examines how mechanisms to address forest loss can contribute to poverty reduction, as well as the importance of preserving other ecosystem services such as biodiversity and water services.

1.1 The Impacts of Climate Change

Climate change is a major global threat. Over the last century, global temperatures have risen by 0.7°C. Sea levels are rising at three millimetres a year and Arctic sea ice is melting at almost three per cent a decade. Continued warming of the atmosphere at the same rate will result in substantial damage to water resources, ecosystems and coastlines, as well as having an impact on food supplies and health.

The economic costs of climate change impacts have been estimated at between 5 and 20 per cent of global GDP, and could be considerably higher.

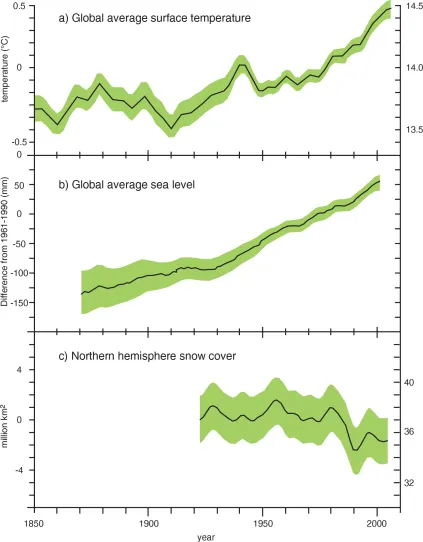

Warming of the earth’s climate system has led to increases in global average air and sea temperatures, rising global average sea levels and widespread melting of snow and ice. As Figure 1.1 illustrates, global average sea level has risen by 3.1 millimetres a year since 1993, with a total 20th century rise estimated at 0.17 metre. Satellite data since 1978 shows that the annual average arctic sea ice extent has shrunk by 2.7 per cent per decade.

Figure 1.1: Changes in temperature, sea level and northern hemisphere snow cover

Source: IPCC (2007) AR4 Synthesis Report

A large number of other climatic changes have also been observed, including:

• an increase in the global area affected by drought;

• more frequent heat waves over most land areas;

• increased heavy precipitation events over most land areas;

• an increased incidence of extreme high sea level worldwide.

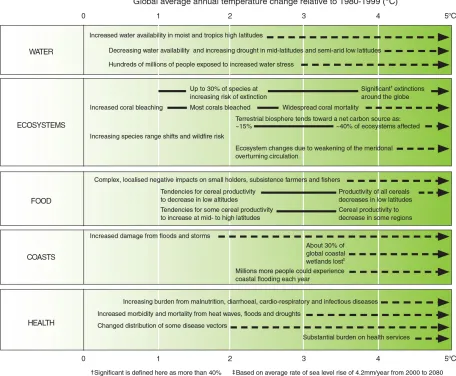

All the emissions scenarios reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) project continued global warming of about 0.2°C per decade for the next two decades. These climatic changes will bring a wide range of impacts, some of which will be irreversible (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Examples of impacts associated with global average temperature change

Source: IPCC (2007) AR4 Synthesis Report

As global temperatures rise, these impacts will become more severe. Millions of people, particularly the poor, will be exposed to an increased incidence of droughts and floods, food and freshwater shortages, disease and the loss of their livelihoods and homes. Developing countries are particularly exposed to the effects of climate change because their economies are so heavily dependent on climate-vulnerable sectors such as agriculture. In addition to the direct costs to humankind, the IPCC suggests that approximately 20-30 per cent of species assessed so far are likely to be at increased risk of extinction if increases in global average temperature exceed 1.5-2.5°C.

The Stern Review considered the physical impacts of climate change on the global economy, on human life and on the environment. It also estimated the damages of climate change, including integrated assessment models that estimate the economic impacts of climate change.

Stern concluded that business as usual (BAU) climate change will reduce welfare by an amount equivalent to a reduction in consumption per person of between 5 and 20 per cent now and into the future. Subsequent analysis, taking account of the increasing scientific evidence of greater risks, of aversion to the possibilities of catastrophe and of a broader approach to the consequences, suggests the appropriate estimate is likely to be in the upper part of this range.

1.2 Climate Change Mitigation

Current evidence suggests that to avoid the worst effects of climate change we should aim to stabilise levels of atmospheric CO2e at 445-490 parts per million (ppm). Achieving this global stabilisation target will require strong and urgent international action.

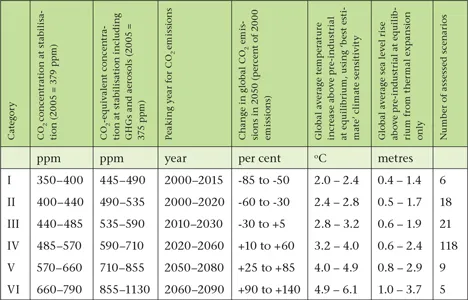

Early action could significantly reduce the risk of severe climate change impacts. In order to stabilise the concentration of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the atmosphere, emissions would need to peak and then decline. The lower the stabilisation level, the sooner this peak would have to occur. Table 1.1 summarises the required emission levels and timescales for different stabilisation trajectories.

Table 1.1: Stabilisation scenario characteristics

Source: IPCC (2007) AR4 Synthesis Report

It is widely suggested that the increase in global temperature that is currently occurring should be stabilised at a maximum of 2°C over pre-industrial levels to minimise the risk of dangerous climate change. The IPCC has indicated in its Fourth Assessment Report that achieving a 2°C target would mean stabilising GHG concentrations in the atmosphere at around 445-490 ppm CO2 – equivalent (e) or lower. Higher levels would substantially increase the risks of harmful and irreversible climate change ...