![]()

Chapter 1

Enter the Triple Bottom Line

John Elkington

In 1994, the author coined the term triple bottom line. He reflects on what got him to that point, what has happened since – and where the agenda may now be headed.

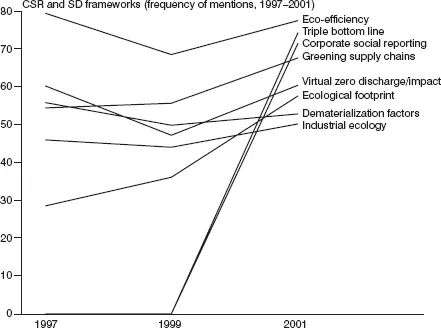

The late 1990s saw the term ‘triple bottom line’ take off. Based on the results of a survey of international experts in corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable development (SD), Figure 1.1 spotlights the growth trend over the two years from 1999 to 2001. As originator of the term, I have often been asked how it was conceived and born. As far as I can remember – and memory is a notoriously fallible thing – there was no single eureka! moment. Instead, in 1994 we had been looking for new language to express what we saw as an inevitable expansion of the environmental agenda that SustainAbility (founded in 1987) had mainly focused upon to that point.

We felt that the social and economic dimensions of the agenda – which had already been flagged in 1987’s Brundtland Report (UNWCED, 1987) – would have to be addressed in a more integrated way if real environmental progress was to be made. Because SustainAbility mainly works, by choice, with business, we felt that the language would have to resonate with business brains. By way of background, I had already coined several other terms that had gone into the language, including ‘environmental excellence’ (1984) and ‘green consumer’ (1986). The first was targeted at business professionals in the wake of 1982’s best-selling management book In Search of Excellence (Peters and Waterman, 1982), which failed to mention the environment even once. The aim of the second was to help mobilize consumers to put pressure on business about environmental issues. This cause was aided enormously by the runaway success of our book The Green Consumer Guide, which sold nearly 1 million copies in its various editions (Elkington and Hailes, 1988).

Source: Environics International

Figure 1.1 The triple bottom line takes off

But back to the triple bottom line (often abbreviated to TBL). Like Paul McCartney waking up with Yesterday playing in his brain and initially believing that he was humming someone else's tune, when the three words finally came to me I was totally convinced that someone must have used them before. But an extensive search suggested otherwise. The next step was whether we should take steps to trademark or otherwise protect the language, as most mainstream consultancies would have done. Counter-intuitively, perhaps, we decided to do exactly the reverse, ensuring that no one could protect it. We began using the term in public, with early launch platforms, including an article in the California Management Review on ‘win–win–win’ business strategies (Elkington, 1994), SustainAbility's 1996 report Engaging Stakeholders and my 1997 book Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business (Elkington, 1997). In 1995, we also developed the 3P formulation, ‘people, planet and profits’, later adopted by Shell for its first Shell Report and now widely used in The Netherlands as the 3Ps.

In the following sections we will look at the drivers of the TBL agenda, at the waves and downwaves in societal pressures on business, at the characteristics of a number of different business models, and at the emerging roles of governments.

Seven drivers

In the simplest terms, the TBL agenda focuses corporations not just on the economic value that they add, but also on the environmental and social value that they add – or destroy.

With its dependence on seven closely linked revolutions (see Figure 1.2), the sustainable capitalism transition will be one of the most complex our species has ever had to negotiate (Elkington, 1997). As we move into the third millennium, we are embarking on a global cultural revolution. Business, much more than governments or non-governmental organizations (NGOs), will be in the driving seat. Paradoxically, this will not make the transition any easier for business people. For many it will prove gruelling, if not impossible.

Figure 1.2 Seven sustainability revolutions

Markets

Revolution 1 will be driven by competition, largely through markets. For the foreseeable future, business will operate in markets that are more open to competition, both domestic and international, than at any other time in living memory. The resulting economic earthquakes will transform our world.

When an earthquake hits a city built on sandy or wet soils, the ground can become ‘thixotropic’: in effect, it turns to jelly. Entire buildings can disappear into the resulting quicksands. In the emerging world order, entire markets will also go thixotropic, swallowing entire companies, even industries. Learning to spot the market conditions and factors that can trigger this process will be a key to future business survival, let alone success.

In this extraordinary environment, growing numbers of companies are already finding themselves challenged by customers and the financial markets about aspects of their TBL commitments and performance. Furthermore, although we will undoubtedly see continuing cycles based on wider economic, social and political trends, this pressure can only grow over the long term. As a result, business will shift to a new approach, using TBL thinking and accounting to build the business case for action and investment.

Values

Revolution 2 is driven by the worldwide shift in human and societal values. Most business people, indeed most people, take values as a given, if they think about them at all. Yet, our values are the product of the most powerful programming that each of us has ever been exposed to. When they change, as they seem to do with every succeeding generation, entire societies can go thixotropic. Companies that have felt themselves standing on solid ground for decades suddenly find that the world as they knew it is being turned upside down and inside out.

Remember Mrs Aquino's peaceful revolution in the Philippines? Or the extraordinary changes in Eastern Europe in 1989? Recall the experiences of Shell during the Brent Spar and Nigerian controversies, with the giant oil company later announcing that it would, in future, consult NGOs on such issues as environment and human rights before deciding on development options? Think, too, of Texaco. The US oil company paid US$176 million in an out-of-court settlement in the hope that it would bury the controversy about its poor record in integrating ethnic minorities. Now, with the dawn of the 21st century, we have a new roll-call of companies that have crashed and burned because of values-based crises, among them Enron and Arthur Andersen.

Transparency

Revolution 3 is well under way, is being fuelled by growing international transparency and will accelerate. As a result, business will find its thinking, priorities, commitments and activities under increasingly intense scrutiny worldwide. Some forms of disclosure will be voluntary, but others will evolve with little direct involvement from most companies. In many respects, the transparency revolution is now ‘out of control’. Even China is being forced to open up by such factors as the global SARS epidemic that it helped to spawn.

This opening up process is itself being driven by the coming together of new value systems and radically different information technologies, from satellite television to the internet. The collapse of many forms of traditional authority also means that a wide range of different stakeholders increasingly demand information on what business is going and planning to do. Increasingly, too, they are using that information to compare, benchmark and rank the performance of competing companies. The 2001 inauguration of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), built on TBL foundations, is one of the most powerful symbols of this trend.

Life-cycle technology

Revolution 4 is driven by and – in turn – is driving the transparency revolution. Companies are being challenged about the TBL implications either of industrial or agricultural activities far back down the supply chain or about the implications of their products in transit, in use and – increasingly – after their useful life has ended. Here we are seeing a shift from companies focusing on the acceptability of their products at the point of sale to a new emphasis on their performance from cradle to grave – that is, from the extraction of raw materials right through to recycling or disposal. Managing the life cycles of technologies and products as different as batteries, jumbo jets and offshore oil rigs will be a key emerging focus of 21st-century business. Nike has been the ‘poster child’ for campaigners in this area; but we will see many other companies fall victim as the spotlight plays back and forth along their supply chains.

Partners

Revolution 5 will dramatically accelerate the rate at which new forms of partnership spring up between companies, and between companies and other organizations – including some leading campaigning groups. organizations that once saw themselves as sworn enemies will increasingly flirt with and propose new forms of relationship to opponents who are seen to hold some of the keys to success in the new order. As even groups such as Greenpeace have geared up for this new approach, we have seen a further acceleration of the trends that drive the third and fourth sustainability revolutions. None of this means that we will see an end to friction and, on occasion, outright conflict. instead, campaigning groups will need to work out ways of simultaneously challenging and working with the same industry – or even the same company.

Time

Time is short, we are told. Time is money. But, driven by the sustainability agenda, Revolution 6 will promote a profound shift in the way that we understand and manage time. As the latest news erupts through CNN and other channels within seconds of the relevant events happening on the other side of the world, and as more than US$1 trillion sluices around the world every working day, so business finds that current time is becoming ever ‘wider’. This involves the opening out of the time dimension, with more and more happening every minute of every day. Quarterly – and even online – reporting requirements are key drivers towards this wide-time world.

By contrast, the sustainability agenda is pushing us in the other direction – towards ‘long’ time. Given that most politicians and business leaders find it hard to think even two or three years ahead, the scale of the challenge is indicated by the fact that the emerging agenda requires thinking across decades, generations and, in some instances, centuries. As time-based competition, building on the platform created by techniques such as ‘just in time’, continues to accelerate the pace of competition, the need to build in a stronger ‘long time’ dimension to business thinking and planning will become ever-more pressing. The use of scenarios, or alternative visions of the future, is one way in which we can expand our time horizons and spur our creativity.

Corporate governance

Ultimately, whatever the drivers, the business end of the TBL agenda is the responsibility of the corporate board. Revolution 7 is driven by each of the other revolutions and is also resulting in a totally new spin being put on the already energetic corporate governance debate. Now, instead of just focusing on issues such as the pay packets of ‘fat cat’ directors, new questions are being asked. For example, what is business for? Who should have a say in how companies are run? What is the appropriate balance between shareholders and other stakeholders? And what balance should be struck at the level of the triple bottom line?

The better the system of corporate governance, the greater the chance that we can build towards genuinely sustainable capitalism. To date, however, most TBL campaigners have not focused their activities at boards; nor, in most cases, do they have a detailed understanding of how boards and corporate governance systems work. This, nonetheless, constitutes a key jousting ground of tomorrow. The Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES) joint venture with innovest on the corporate governance aspects of the risks associated with climate change is an early example of the trend.

It is clear that a growing proportion of corporate sustainability issues revolve not just around process and product design, but also around the design of corporations and their value chains, of ‘business ecosystems’ and, ultimately, of markets. Experience suggests that the best way to ensure that a given corporation fully addresses the TBL agenda is to build the relevant requirements into its corporate DNA from the very outset – and into the parameters of the markets that it seeks to serve. An early example here would be the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX), which is experimenting with the trading of greenhouse emissions.

Clearly, we are still a long way from reaching this objective; but considerable...