![]()

PART

I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

CHAPTER

1

THE NATURE OF UNDERSTANDING

One of the most notable things about children is that they are very organized, intelligent, and adaptive. They have the ability to acquire a prodigious amount of information about their world and to represent and interpret that information in a way that not only makes sense but equips them to solve a huge, and largely unpredictable, array of problems. This book is about how children acquire information, how they represent it, and how they use it to build problem-solving skills. With this information I hope to explain why children understand things the way they do and how they use that understanding in solving problems.

Although the book is concerned with basic processes in cognitive development, understanding is emphasized because it confers a certain cognitive autonomy on the child. To the extent that children understand something, they can devise their own way of representing it and dealing with it. They can also devise new ways of dealing with changed circumstances they might meet in the future. Furthermore they can use their understanding as a basis for acquiring further information. In effect, understanding is one of the most valuable acquisitions a child or anyone else can make. Furthermore the processes entailed in understanding constitute a major challenge for contemporary cognitive science.

This book is concerned with children’s understanding of concepts and with the way that understanding is used for such processes as making inferences, developing problem-solving strategies, organizing memory, and aiding learning. It will be argued that understanding plays a crucial role in cognitive development, but it needs to be considered in relation to other basic processes such as learning, memory, and development of capacity.

The term understanding can apply to an extremely wide range of activities, including language comprehension, reading, problem solving, and memory. It would obviously not be possible to cover all these topics in one book, even were it desirable to do so. Instead, I examine the basic processes entailed in understanding and the role they play in cognitive development.

The controversy concerning the utility of understanding as a topic for scientific enquiry that once existed between gestalt psychologists on the one hand and learning theorists on the other has now passed us by and has been replaced by a new consensus. Although gestalt psychologists considered understanding important and emphasized representations, “seeing” the problem, and insight as basic factors in thought (Humphrey, 1951), psychologists working within the learning theory tradition regarded such notions as unscientific and subjective. Thus, Bugelski (1964) contended that “understanding does not contribute anything but a feeling of satisfaction” (p. 204). Since that time, and especially in the last decade, there seems to be growing recognition that understanding plays an important role in learning and thinking, especially with respect to the acquisition and use of mathematical, scientific, and technological concepts (Gentner & Stevens, 1983; Resnick, 1983b).

There are several reasons for the growth of interest in understanding as a topic of scientific enquiry. One has been the development of cognitive models that give a rigorous definition of what it means to understand something. For example, Simon and Hayes (1976) developed a program called UNDERSTAND that could interpret natural language descriptions of a problem and create an appropriate representation or problem space. Another influence was the work of Gelman and Gallistel (1978), which indicated that children’s counting was not based solely on the exercise of mechanical skills but reflected understanding of counting principles. Then Greeno, Riley, and Gelman (1984) produced a computer simulation model of the constraint exercised by elementary number concepts on counting strategies. This meant that not only could understanding be defined rigorously but the way it influenced actual performance could be modeled in detail.

The importance of understanding has also been clearly seen in research on mathematical and scientific education. It has been found that children’s errors in arithmetic are often based on faulty understanding or, more frequently, on failure to apply the understanding they have (Resnick & Omanson, 1987). It has also been found useful to analyze what is entailed in mathematicians’ understanding of their discipline (Michener, 1978). Investigation of high school and college students’ performance on problems in physics has shown that misunderstandings persist even after courses are successfully completed (McCloskey, 1983). This has led to increased interest in ways of promoting understanding and guiding children to develop rational justification for their problem-solving strategies (Resnick, 1983b).

Research on cognitive development, particularly within the Piagetian context, has frequently revolved around the question of what children understand. It has often been a matter of contention as to whether, for example, preschool children genuinely understand concepts like conservation and classification or whether their apparent successes are based on mechanical application of rules. I have reviewed this issue elsewhere (Halford, 1982, 1989), but in this book I try to show that a better definition of understanding can sharpen long-standing issues in cognitive development and lead to new insights. It is more useful to specify the mental model that a child has of a concept than to categorize the child as understanding or not understanding that concept.

UNDERSTANDING AND MENTAL MODELS

Understanding entails mental models, and the growth of interest in understanding was reflected in two books both using the title Mental Models, both published in the same year (Gentner & Stevens, 1983; Johnson-Laird, 1983). This interest is largely due to our realization that the type of mental models that we have profoundly influences the expectations we have about the world, the way we go about solving problems, and the way we acquire new knowledge.

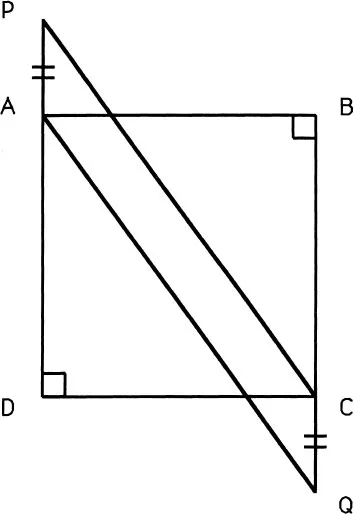

To set the stage for our argument, we briefly consider some examples of the way mental models influence our ability to solve problems. Figure 1.1 shows a gestalt area problem that originated with Wertheimer and was discussed by Humphrey (1951). The figure ABCD is a square, and AP = CQ. The problem is to find the area of the square ABCD plus the parallelogram, APCQ. According to Gestalt psychology, the essential step is to see that the problem may be represented as two triangles, PDC and AQB. The sum of these two triangles equals the required area, so the solution is PD x AB, or an equivalent. The striking thing about this problem is how much easier it is once the right mental model is adopted. The restructuring of the original problem representation into the much more advantageous representation based on the sum of two triangles is an example of what the gestalt psychologists called “insight.” Another example of the way mental models can facilitate or inhibit problem solving occurs in the well-known problem about the car and the bird. A car makes a journey from Town A to Town B, 100 miles apart, and travels at 25 miles per hour. At the moment the car leaves A, a bird leaves B, flies towards the car at 50 miles per hour and, on reaching the car, returns to B. Then it flies out to meet the car again, returns to B, and so on until the car reaches B. How far does the bird fly?

Attempts to solve the problem by calculating the time of each out-and-return journey, then summing the times, leads to a very complex series, with cumbersome calculations. A better “mental model” is to say that since the car will take 4 hours to travel from A to B, and the bird flies at 50 miles per hour, then the bird flies 200 miles.

FIG. 1.1. Gestalt area problem.

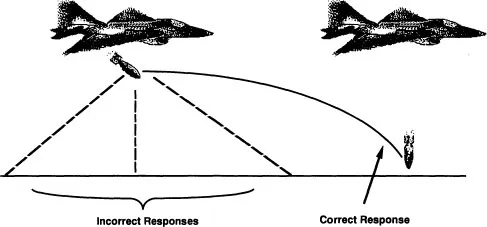

The importance of mental models, as we noted, has been highlighted in the context of scientific education. A problem investigated by McCloskey (1983) is illustrated in Fig. 1.2. Students are asked to say where a bomb will land after it is dropped from an aircraft, ignoring air resistance. The correct solution is that the bomb will travel a parabolic path, striking the ground directly beneath the aircraft. Some of the incorrect solutions offered by students are shown. These errors are found to occur because of naive mental models about motion. Some students believe, even after completing courses on mechanics, that an object moves because it receives an “impetus” to move, and that the impetus is lost over time. In this case the bomb receives the impetus to move from the plane, and when it leaves the plane it loses the impetus. This leads to a variety of incorrect solutions, such as that the bomb falls between the release point and the point that the plane has reached by the time bomb hits the ground, that the bomb falls straight down, or even that the bomb falls behind the point where it was released. Empirical study showed that even some students who had passed their examinations in the subject did not understand the basic principles of Newtonian mechanics exemplified in this problem.

Our final example of the importance of mental models concerns a classic finding in the field of cognitive development. The paradigm was one that was developed by Bryant and Trabasso (1971) to assess young children’s ability to make transitive inferences (e.g., a < b, b < c, therefore a < c). It entailed training children with relative lengths of pairs of colored sticks, so that for example the red stick was shorter than the blue stick. The sticks formed an ascending series, with Stick 1 the shortest and Stick 5 the longest. Having been trained on the adjacent pairs, 1 < 2, 2 < 3, 3 <4, 4 < 5 (and the inverses 2 > 1, etc.), children were tested on all possible pairs. Performance on the pair 2 < 4 was regarded as the test of ability to make transitive inferences, because it requires the inference 2 < 3, 3 < 4, therefore 2 < 4.

Trabasso, Riley, and Wilson (1975) increased the length of the series, so there was a fifth pair such that 5 < 6. This raises the interesting possibility of comparing one- and two-step transitive inferences. Comparison of 2 with 4, or 3 with 5 entails a one-step inference; for example, 2 < 3, 3 < 4, therefore 2 < 4. Comparison of 2 with 5 entails a two-step inference; 2 < 3, 3 < 4, therefore 2 < 4, then 4 < 5, therefore 2 < 5. The more complex sequence of steps required for the two-step inference makes it appear virtually certain that it would be more difficult, producing longer decision times and more errors. Empirical results were the opposite of this, the two-step inference actually being faster and more accurate.

FIG. 1.2. Problem concerning laws of motion.

The reason for this result is now very well known. Study of serial position effects showed that both children and adults performed this task by constructing an ordered array. That is, they encoded the premises as an image, or a verbally rehearsed string, with the elements in the order 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, (6). Thus the mental model that people used was not based on making inferences from separate premises, 2 < 3, and 3 < 4 and so on, but on accessing an integrated array representation. Once the problem elements are assembled into the array, any comparison could be made easily by accessing the array; we only have to examine the array to see that 2 < 3, 3 < 4, … 2 < 5 and so on. Moreover, the further the elements in the array are separated, the clearer the difference between them. This is an example of the symbolic distance effect; the more different two mental symbols are, the more easily they are distinguished. This explains why the two-step inference, 2 < 5 is easier than one-step inferences 2 < 4 or 3 < 5.

The very extensive literature on transitive inference has been the subject of a number of reviews (Breslow, 1981; Halford, 1982; Thayer & Collyer, 1978; Trabasso, 1975, 1977). This program of research illustrates how the knowledge of the mental model that is used for a task clarifies the nature of the person’s performance. We could argue endlessly over whether children of a particular age should be categorized as understanding transitivity on the basis of this evidence. It is more useful to know what mental processes they employ in performing the task. Their performance on this and related tasks can then be predicted. This is not to argue that there are no important age differences in the task. On the contrary, in many of the concepts we examine, including transitivity, there are very significant age differences, and they represent some very important principles. However these principles can be recognized more clearly by defining precisely the mental models used rather than by categorizing children according to some arbitrarily defined mastery criterion.

I also want to illustrate an argument that is taken up in a number of contexts later in this book. It is that analysis of understanding can often explain why tasks are difficult. Understanding of transitive inference entails constructing an ordered set of premise elements; in this case the set of sticks in the order 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, (6). The construction of this ordered set representation is responsible for part of the difficulty of transitive inference. To see why this is so, consider the problem “Peter is happier than Tom, Bill is happier than Peter, who is the happiest?” Most of us experience some slight feeling of effort in solving the problem. I suggest the reason is that both premises have to be processed jointly in order to construct the correct order. From the first premise we know that (for example) Peter belongs in Position 1 or 2, but we do not know which. From the second premise we know that Peter is in Position 2 or 3, but again we would not know which from the second premise alone. Only by considering both premises jointly can we determine the position of Peter uniquely. A similar argument applies for Tom and Bill. Both premises must be processed jointly to determine the correct ordinal position of any element in the problem.

Tasks like this that require relations to be considered jointly in order to construct an appropriate mental model are difficult, both for children and adults. I suggest that whereas our information processing capacity is prodigious, even virtually unlimited in some respects, we have quite restricted capacity for this type of performance. In fact it is not hard to put even adult processing capacity under a strain with this type of problem. To illustrate, consider this problem:

Wendy is taller than Mark.

Bill is taller than Jenny.

Jenny is taller than Wendy.

What is the correct order of height?

Most people find this a moderately effortful task, and success rates as low as 50% have been obtained on problems of this form with adults (Foos, Smith, Sabol, & Mynatt, 1976). The source of the difficulty is to be found in the amount of information that has to be stored and processed in a single step, when the third premise (Jenny is taller than Wendy) is processed. Analysis of these storage and processing loads sheds a lot of light on difficulties experienced in cognitive tasks. This example also illustrates another theme of this book. The difficulties that children experience with tasks like transitive inference are not unique to children but affect adults also, because they reflect fundamental properties of human cognitive architecture. They just affect children more, for reasons that we will explore later. One purpose of this book is to define, explain, and suggest ways of overcoming, such limitations.

NATURE OF UNDERSTANDING

The term understanding...