Sustainable Development Projects

Integrated Design, Development, and Regulation

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Sustainable Development Projects

Integrated Design, Development, and Regulation

About this book

Development projects are the building blocks of urban growth. Put enough of the right projects together in the right way, and you have sustainable cities. But getting the pieces to stack up takes a feat of coordination and cooperation. In our market economy, developers, designers, and planners tend to operate in silos, each focused on its own piece of the puzzle.

Sustainable Development Projects shows how these three groups can work together to build stronger cities. It starts with a blueprint for a development triad that balances sound economics, quality design, and the public good. A step-by-step description of the development process explains how and when planners can most effectively regulate new projects, while a glossary of real estate terms gives all the project participants a common language.

Detailed scenarios apply the book's principles to a trio of projects: rental apartments, greenfield housing, and mixed use infill. Readers can follow the projects from inception to finished product and see how different choices would result in different outcomes.

This nuts-and-bolts guide urges planners, developers, and designers to break out of their silos and join forces to build more sustainable communities. It's essential reading for practicing planners, real estate and design professionals, planning and zoning commissioners, elected officials, planning students, and everyone who cares about the future of cities.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: Challenges to Sustainable Urban Growth

- Local government planners prepare and implement comprehensive plans that seek to guide future development toward sustain able outcomes (Godschalk and Anderson 2012; Kelly 2009; Berke, Godschalk, and Kaiser 2006; Anderson 1995). These planners, in coordination with officials and citizens, lay out desired future land-use and infrastructure patterns to be implemented through zoning; subdivision regulations; capital improvement programs; and other public sector actions, policies, and development controls. Ideally, such planning is based on an overall understanding of the economic consequences of plan adoption and implementation at both the community and neighborhood level. At the project scale, the plan is administered through zoning ordinances and other development regulations, requiring that planners become regulators in addition to fulfilling their broader roles (Talen 2012; Elliott, Goebel, and Meadows 2012).

- Real estate developers envision and propose development projects that seek to provide sustainable additions to the stock of housing and commercial property in the community (Peiser and Hamilton 2012, Peca 2009, Miles et al. 1991). These developers, in coordination with banks and equity investors, take advantage of opportunities to create urban values through investing in and developing properties. In essence, developers act as urban change agents, finding financial support and taking risks that their projects will be accepted as desirable ways to realize the urban growth contemplated in the comprehensive plan and guided by the existing development standards and regulations.

- Design and planning consultants translate development concepts into site plans, engineering schemes, and landscape and architectural visions that seek to carry out development project goals and objectives (Lu 2012, Dinep and Schwab 2010, Russ 2009, LaGro 2008, Simonds and Starke 2006, Lynch and Hack 1984). These consultants, often working in teams, do the pragmatic work necessary to fit the project onto the site, ensure that it will meet professional practice standards, consider its relationship with its context, and enable it to be permitted under the applicable development regulations. Drawing on the community's plan and vision, and the developers notion of a successful project, these consultants craft alternative proposals for the flesh-and-blood realization of this particular set of structures. They combine specialized professional knowledge with aesthetic values in order to test possible designs against local codes and sustainability standards.

Challenges of Guiding Urban Growth

An Integrated and Balanced Approach

- Design elements—the form, density, and site layouts of new residential, commercial, office, and mixed use projects, formulated by architects, landscape architects, and engineers, as expressed in architectural plans and site plan drawings.

- Development feasibility—the financial returns and construction costs analyzed by real estate developers to assess the risks of undertaking development and redevelopment projects, as expressed in financial models and pro formas comparing project revenues and expenditures.2

- Regulatory standards—the land-use and public-facility requirements of local government regulations and policies written and enforced by urban planners and public officials to govern and guide the design of development projects, as expressed in development project reviews conducted in accordance with zoning and subdivision ordinances, design guidelines, and public policies.

- Project design and site plan preparation is typically guided by professional best practices, design standards, legal codes, and regulations, rather than explicitly by the economic and financial dimensions of projects. The basic goal of this process is to craft designs that will be approved by clients and regulatory agencies; if designs also gain plaudits and awards from the design community, then that represents an even higher level of success.

- Development feasibility analysis is typically based on expected rates of return from standard designs rather than from design alternatives geared to unique site and environmental conditions or aimed at creating outstanding architecture. The basic goal of this process is to propose projects that will be financially successful and will be readily approved by local regulatory agencies; if the proposals also help to establish the developers' reputations and lead to further business opportunities, then that is an even higher level of success.

- Regulatory review is typically carried out to implement standards and objectives in comprehensive plans, zoning and subdivision regulations, building codes, and public facility policies rather than as a conscious attempt to use incentives and criteria to achieve design and financial objectives. The basic goal of the review process is to e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Introduction: Challenges to Sustainable Urban Growth

- Chapter 2. Design, Development, and Regulation Silos

- Chapter 3. Linking Project Design, Development, and Regulation

- Chapter 4. Apartment Project Alternatives

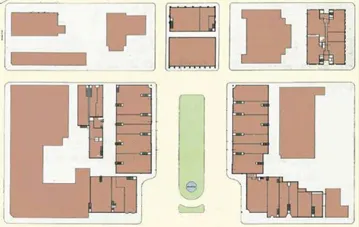

- Chapter 5. Residential Subdivision Alternatives

- Chapter 6. Dynamic Financial Analysis

- Chapter 7. Infill Redevelopment Alternatives

- Chapter 8. Development Coordination Recommendations

- Notes

- Glossary of Real Estate Development Terms

- References

- About the Authors

- Index