![]()

COGNITIVE THEORY OF EVERYDAY LIFE

Everyday life is characterized by conscious purposiveness. From reaching for food to designing an experiment, our actions are directed at goals. This purposiveness reveals itself partly in our conscious awareness, partly in the organization of our thought and action. Everyday life is thus an obvious, seemingly ideal place to begin, filled with promise for development of cognitive theory.

This promise has been tantalizing in the original Greek sense of that term: Tantalos, a son of Zeus and a king, was condemned in the afterlife to stand, racked with hunger and thirst, amid fruit-laden boughs in water up to his chin—with the fruit and water receding at each attempt to eat and drink. Many present-day psychologists feel like Tantalos. Our awareness of our feelings, desires, and goals ought to have shown the way to deeper understanding. Our immediate experience ought to have lighted a path to scientific theory. Many writers have sought to develop psychological theory on the basis of conscious experience. But, as with Tantalos, the sought-for understanding has receded at each attempt to eat and drink.

This recalcitrance of everyday experience to scientific development caused the dissolution of the original school of introspection. The main successor, the behaviorist movement, reacted against introspection by exiling consciousness. The psychoanalytic movement, otherwise very different, moved the prime locus of mental life to an unconscious realm, generally inaccessible to conscious awareness. The modern cognitive movement has welcomed consciousness home from exile, but has been deaf to affect and emotion. Since affect and emotion are central in our daily experience, these cognitive theories cannot say much about everyday life.

The theme of this volume is that scientific theory can be constructed around the concepts of everyday life. Everyday concepts are thus the focus of study, with the expectation that they can be established as scientific concepts. A partial list of everyday concepts will illustrate the broad field for study:

Psychophysical sensations such as sweetness and loudness.

Perceptual judgments such as size, distance, and movement.

Physical concepts such as time and torque.

Decision concepts such as cost, benefit, and probability.

Physiological reactions such as thirst, fatigue, and pain.

Emotional reactions such as joy and fear.

Interpersonal reactions such as admiration and envy, love and hate.

Moral judgments such as fairness and blame.

Goal experiences such as failure and success.

Self-concepts such as pride and ability.

Ego defenses such as excuses and self-pity.

And many more.

A good beginning has been made in the theory of information integration (IIT). IIT provides a unified, general theory of everyday life. Its generality appears in the spectrum of chapter titles, from person cognition and cognitive development to decision theory and language processing. Its unity appears in the applicability of the same concepts and methods across all these domains.

Moreover, IIT has a solid empirical foundation. It is not another promissory note. It is not only a manifesto but a working reality. It opens onto a new horizon in psychological science.

INFORMATION INTEGRATION THEORY

Two characteristics are basic to IIT. First is the functional perspective, which focuses on purposiveness of thought and action. Second is cognitive algebra. These two are interlinked: Purposiveness imposes a value representation that makes cognitive algebra possible; cognitive algebra provides effective analysis of value and hence of purposiveness.

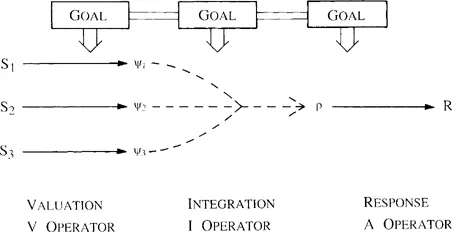

This chapter gives a conceptual overview of IIT. This first part begins with the unifying theme of purposiveness. Purposiveness leads to two fundamental problems, multiple determination and personal value, and thence to concepts summarized in the integration diagram of Figure 1.1, collectively called the problem of the three unobservables.

The second part of the chapter illustrates method and theory with an experimental study of cognitive algebra in person cognition. The third part amplifies the functional perspective with topical discussions of meaning invariance, non-consciousness, motivation, functional memory, and knowledge systems. The chapter concludes with a discussion of strategy of theory construction.

AXIOM OF PURPOSIVENESS1

Purposiveness is the prime axiom of psychology. The purposiveness of behavior has two main implications for IIT. The first is a functional perspective: Thought and action are conceptualized in terms of their functions in goal-directed behavior. This functional perspective entails sometimes substantial changes from customary views. Everyday life requires a functional conception of memory, for example, which is very different from the traditional conception of reproductive memory. Again, nonconscious emotion, which is virtually defined into nonexistence in traditional emotion theories, is an integral part of functional cognition.

The second implication of purposiveness, derived from the first, provides a means for its analysis. This is a one-dimensional representation of cognition. Thought and action have a basic approach-avoidance character; they are directed toward or away from goals. This is clear with affective senses, such as taste, temperature, and sex. These senses embody approach- avoidance polarity, which has evolved for goal-relevant function.

In everyday life, also, approach-avoidance is a fundamental axis of thought and action. Sports are typically centered on winning and losing, and similar success-failure dimensions appear in work and achievement. Our reactions to other persons exhibit a basic like-dislike dimension. An overall dimension of satisfaction-dissatisfaction pervades married life. These approach-avoidance continua represent purposiveness in a dimensional form.

This one-dimensional representation is encapsulated in the concept of value. Values embody and represent goal-directed thought and action. Although a one-dimensional value representation omits much of importance, it captures something of first importance, namely, goal directedness. Approach and avoidance are represented by positive and negative values associated with goals. With this one-dimensional representation, quantitative analysis of complex behavior becomes thinkable.

But values must be measured. Measurement is necessary to quantify goal directedness. Measurement is necessary to actualize the value representation.

Measurement of values has long been controversial in psychology, even for simple sensations such as sweetness and loudness. We have no sucrometer to place on your tongue to measure your sensation of sweetness, nor any audiometer to implant in your auditory cortex. Even more problematic is measurement of feelings of affection, blame, unfairness, and other everyday experiences. Without a solution to this problem of value measurement, the one-dimensional representation of goal directedness has limited usefulness.

By a blessing of Nature, the measurement problem has a solution. The key came with the discovery of cognitive algebra. Work on IIT has revealed algebraic rules in nearly every domain. The stimulus terms in these algebraic rules embody one-dimensional values; the response term embodies the one-dimensional character of goal directedness. Stimulus and response measurement are both possible with cognitive algebra.

Moreover, cognitive algebra can operate at the level of conscious phenomenology, yet still analyze nonconscious concepts. Cognitive algebra thus provides a key to unlock the promise of conscious purposiveness.

MULTIPLE DETERMINATION

Virtually all judgment and action depend on more than one determinant. This is obvious in our social behavior. When we discipline a child, our action depends not only on the transgression, but also on our attribution about the child’s intent, our desire to punish or instruct, and so on. When we meet a woman, we are influenced by her facial appearance and makeup, smile and gesture, dress, qualities of voice and language, and content and style of conversation. Marriage satisfaction depends on personal appreciation and quality of sex from your spouse and also on finances and children. Small moral problems, such as admitting fault or lying to save face, are everyday examples of conflicting factors. Such multiple determination is basic throughout the social-personality domain.

Multiple determination is equally important in other domains. In psycho-physics, the taste of our food and drink depends not only on several sensations of the tongue, but also on visual cues and odor. Purchase decisions depend on cost-benefit analysis, taking account of price, quality, appearance, and other attributes. Understanding language depends on syntactic and semantic elements and also on contextual variables. Opinions on any professional issue, from education of graduate students to promising and unpromising problems for research, involve multiple pros and cons.

Development of general cognitive theory rests squarely on capability for analysis of multiple determination. This problem has resisted attack. Many psychological experiments, it is true, manipulate two or more variables and obtain multivariable tables of data. Such data tables, however, are generally descriptive and situation-specific. Sometimes they represent important phenomena; sometimes they are useful in testing local hypotheses. However, they do not lead to general theory.

Indeed, the disheartening but common conclusion of an extensive research program is that “it all depends.” Each new variable requires qualification of previous generalizations. The pattern of results grows more complicated with each new study. The more that is learned, the farther away theoretical unification recedes.

Cognitive algebra provides a new approach to multiple determination. It focuses on integration, that is, the rules whereby the various determinants are integrated into a unitary response. This can provide a foundation for theory because the same integration rules can apply to varied sets of determinants. Cognitive algebra can thus provide an underlying order and unifying framework for the surface complications of the innumerable determinants of thought and action. The effectiveness of this line of attack will be demonstrated in each later empirical chapter.

The development of cognitive algebra, however, involved a second basic problem. This is the problem of psychological measurement, considered next.

PSYCHOLOGICAL MEASUREMENT

The concept of value, as already emphasized, offers a fundamental simplification of purposiveness. But values are personal. The importance and promise you attach to your own research often differ from the opinions of reviewers and colleagues. A wife’s feelings of affection for her husband differ in many ways from his for her. Values differ across cultures; across social groups within each culture; and across individuals within each social group.

This basic fact of individual differences has been a quagmire for psychological science. How can general truths be established when individuals may differ sharply in the values that govern their thought and action? And how can individuals be understood without capability for measuring their personal values?

Both questions can be answered by cognitive algebra. Individuals may exhibit similar rules of multiple determination even though they differ in the personal values operative in these rules (see Figure 1.2). Some of these rules have algebraic form—this cognitive algebra provides a grounded theory of psychological measurement, with the needed capability for measuring personal values. The concepts and methods of this approach are outlined next.

INTEGRATION DIAGRAM

A conceptual overview of IIT appears in the simplified integration diagram of Figure 1.1. The organism is considered to reside in a multivariable field of observable stimuli, denoted by S1, S2, …, at the left of the diagram. These multiple stimuli are determinants of the observable response, R, at the right of the diagram. Between the observable stimuli and the observable response intervene three processing operators: valuation, integration, and action, denoted by V, I, and A, respectively.

Also represented in the integration diagram is the operative goal, which controls all three processing operations. The purposiveness of thought and action is thus explicitly incorporated in the integration diagram. All three operators, accordingly, embody the construction principle discussed later.

The valuation operator, V, extracts information from stimuli. In the integration diagram, it refers to processing chains that lead from the observable stimuli, Si, to their psychological representations, denoted by ψi. Valuation may be as simple as tasting the sweetness of a drink or as difficult as interpreting the complaints of your spouse.

Figure 1.1. Information integration diagram. Chain of three operators, V-I-A, leads from observable stimulus field, {S}, to observable response, R. Valuation operator, V, transforms observable stimuli, Si into subjective representations, ψi,. Integration operator, I, transforms subjective stimulus field, {ψi}, into implicit response,ρ. Action operator, A, transforms implicit response, ρ, into observable response, R. (After N. H....