![]()

In your lack of power to finish anything lies the secret of your greatness.

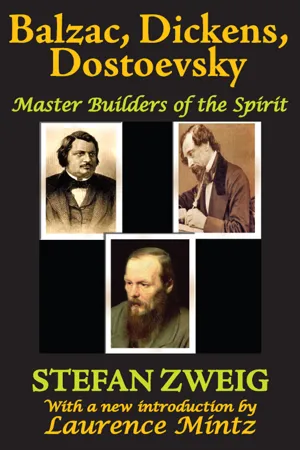

GOETHE

Dostoeffsky

1821–1880

THE EXPLORATION OF A NEW COSMOS

LIKENESS

TRAGEDY OF HIS LIFE

THE MEANING OF HIS DESTINY

DOSTOEFFSKY'S CHARACTERS

REALISM AND FANTASY

ARCHITECTURE AND PASSION

THE TRANSGRESSOR OF BOUNDARIES

TORMENTED BY GOD

VITA TRIUMPHATRIX

![]()

THE EXPLORATION OF A NEW COSMOS

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies …

KEATS

IT is a difficult task, one full of responsibility, to write worthily of Fedor Mihailovich Dostoeffsky, and to set forth adequately all he signifies for the inner life of the contemporary world. Indeed, the breadth and the power of this one individual demand from us a new standard of measurement.

Approaching him as we should approach another, we expect to find a circumscribed imaginative work, the creation of a man subject to the ordinary limitations; instead, we are confronted with boundless expanses, with a cosmos having its own circling stars and making its own music of the spheres. Discouragement overwhelms the voyager into these realms: his first experience of their magic is too alien, the range of their ideas is too vast, their message is too exotic, to permit him to gaze undazzled into their heavens and feast his eyes as he does on more familiar skies. To be fully appreciated, Dostoeffsky must be lived from within. We must probe our own powers of sympathy and compassion to the depths, we must attune our hearts to a fresh and enhanced sensibility, we must delve down to the roots of our being, if we would discover the correlations between our own nature and human nature as envisaged by Dostoeffsky—for at first we think his conception fantastical, to learn in the end that it is amazingly true to life. We can only hope to make ourselves bone of his bone and flesh of his flesh if we have the courage to fathom to the lowest abysses of our personality, to penetrate to what is eternal and unchangeable in our essence, to search out the ultimate fibrils of our innermost self.

How strange this Russian countryside seems at the first approach; a careless glance, and the steppe of Dostoeffsky’s homeland would appear a pathless waste, remote and having little kinship with the familiar scenes of the west. No friendly contours are there to caress the eye; rarely does a suave hour invite the traveller to repose. A twilight scarred with lightning-flashes and fraught with mystery encompassing the senses alternates with an extreme of frost and ice which clarifies the mind; no warm, bright sunshine to fill sky and earth with gladness, but the northern lights flaming blood-red athwart the heavens. We are confronted with a primeval landscape, a magic world of Dostoeffsky’s own creation; pregnant with manifold experience, and yet at the same time virginal. A tremor seizes us, a tremor not wholly unpleasant, as if we were approaching the everlasting elements. Before long our mood prompts us to linger, giving our admiration rein; and yet a boding knowledge informs us that here is no region wherein we may make ourselves at home for ever; soon we have to return to our own warmer and friendlier, though maybe narrower, world. Shame assails us as we realize that this iron landscape is too great for everyday contemplation; the alternations from an icy to an ardent atmosphere and back again make it hard to draw breath. The spirit might well quail before the majesty of so much horror, were it not that, above the tragic welter, an unending expanse of goodness is spread, starry and serene; the selfsame skies enclosing the world we know, but higher, more spacious, more intellectually sharp and glacial, than those which form the canopy over our gentler zones. Only when reassured by an upward glance from earth to the skies above, can we attain infinite consolation for the infinite passion of the human lot, perceiving greatness ambushed in the horror, divinity hidden in the gloom.

Such a glance into the empyrean is alone capable of transforming into an ardent love the awe which inspires us when contemplating Dostoeffsky’s work; only by a searching penetration into his unique qualities can we gain a clear understanding of the profound sense of brotherhood and the all-embracing humanity which permeate the life and writings of this mighty Russian. But how labyrinthine are the ways into his heart! Vast is the expanse, dread are the horizons, that open up before our vision; and as we pass from the limitless immensity into the unfathomed depths, the work of the master becomes more and more enigmatic. It is, indeed, saturated With mystery. Each character beckons us down into the daimonic abysses of the terrestrial, or swings us heavenward to God’s very throne. Behind each division of his work, each face of his creations, each fold of his disguise, there broods eternal night or shines eternal day: for life and destiny have decreed that Dostoeffsky shall be kin to all the mysteries of existence. His universe hangs betwixt death and madness, dreams and sharp-cut reality. His personal problem is incessantly colliding with the insoluble problem of all mankind; every shining surface reflects immortality. As a man, as an imaginative writer, as a Russian, as a political propagandist, as a prophet, no matter the aspect under which we consider him, his whole personality irradiates eternal purpose. No road leads to the goal of his being, no question ever allows us to penetrate to the ultimate recesses of his heart. Enthusiasm alone is permitted to approach him; and even enthusiasm must be modest and unassuming, must appear less ardent than our author’s own loving reverence before the mystery of mankind.

Dostoeffsky never holds out a hand to help us approach him. Other master builders of our day have revealed their intentions. Wagner gave us, in addition to his work, a prefatory explanation and a polemical defence; Tolstoy flung the doors of everyday life wide, he accosted those who came to inquire and encouraged the curious. But Dostoeffsky only allows us to examine his finished work; the outline sketches which might have enlightened us as to his motives have been consumed in the fires of creation. Silent and shy, he passed on his way through life, and we are hardly given a glimpse even at the outward and physical facts of his existence. It was only during his youth that he could boast of having friends: as a grown man he was a solitary, for he considered he would detract from his love of humanity as a whole if he were to show marked affection for any one individual. His very letters (save perhaps those to Anna Grigorevna), when they voice complaints and utter cries of distress, betray no more than the general stringency of his life, disclose no more than the dumb pangs of a tortured body. As far as an individual appeal is concerned, his lips are closed. Whole years of his childhood are submerged in the shadows. Though there are many living today who have beheld him in the flesh, yet as a man he has already become intangible and aloof; a legend is growing up around his name, he has acquired the lineaments of a hero and a saint. The twilight of mingled fact and fancy which obscures as much as it illuminates the mortal integument of Homer or Dante or Shakespeare, does the same service to that of Dostoeffsky, giving unearthly lustre to his traits. We cannot hope to write of his destiny if we rely on information gleaned from concrete documents: love alone, love informed with knowledge, must be our guide.

Unaided and undirected must we betake ourselves into the labyrinth of this soul; our only clue, a loving heart freed from the thraldom of earthly passion. The farther we venture on our way, the more aware do we become of our own selves; and it is only when we have attained to a realization of our common kinship with universal humanity, that we really draw near the master. One who knows himself well, knows Dostoeffsky well; for if any man has succeeded in realizing the quintessence of all things human, it is surely he. The road to an understanding of his work leads through the purgatory of the passions, through the hell of tribulation, through every realm of human torment: torment of man and of mankind; torment of the artist; and the ultimate, most agonizing torment of all, the torment of one who is tormented by God himself. The way is dark: if we are not to lose the trail we must light it from the fires within, fanning them to a blaze by our passionate desire for truth. We must first explore the intricacies of our own personality, before hazarding ourselves into his. He sends no herald to lead us forward. Nor has he any means of testifying his presence, save the artist’s mystical trinity of flesh and spirit: his countenance, his destiny, and his work.

![]()

LIKENESS

DOSTOEFFSKY’S face is the face of a peasant. An ashen hue pervades the hollow cheeks, making them appear almost grimy, emphasizing the furrows caused by many years of suffering; the skin, dry and parched, is stretched tight over the bony framework, and is bereft of blood and colour, sucked clean of life by the vampire which has preyed on it for a score of years. To right and left, two huge boulders jut forth, the prominent cheek-bones typical of his race; a sparse moustache and a straggling beard veil the sad-looking mouth and delicate chin. Earth, rock, and forest; a tragical and primitive landscape; such are the basic lineaments of Dostoeffsky’s countenance. All is dark and preeminently earthly in this unbeautiful face. I have called it a peasant’s, but I might almost term it a beggar’s, so flat and colourless is it, so lacking in brightness: a piece of the Russian steppe cast high and dry upon the stones. Even the deep-set eyes, gleaming from within their sockets, are incapable of imparting a spark of light to the grim visage, for their radiance is directed inward. As soon as the lids close over them, the face becomes a death-mask, and the nervous tension which otherwise grips the frail features is relaxed into a lifeless lethargy.

The first feeling we are aware of as we look is repulsion. This initial sensation is gradually replaced by one of growing fascination and admiration; for, crowning the narrow, peasant face, there rises the dome of the forehead, gleaming white above the dark shadows; sculptured marble dominating the clay of the fleshly tenement and the scraggy wilderness of beard. All the shafts of light stream upwards in this face; our gaze becomes absorbed in the broad and kingly brow to the exclusion of the rest; and as the years pass by, and age and illness work havoc among the features, the brow acquires a growing lustre and irradiates light far and wide. It stands like the heavens, high and unassailable, above the body wasted by illness, a glorious symbol of the triumph of the spirit over earthly misery. Nowhere does this triumph find better expression than in the mask which was taken when Dostoeffsky lay dead, his lids loosely blotting out the agonized eyes, his pale fingers gripping the poor little wooden cross which a compassionate peasant woman had given him in the days of his penal servitude. In this cast, the forehead shines forth over the soulless countenance like the rising sun over a benighted landscape, revealing to us the selfsame message that is enshrined in Dostoeffsky’s works: spirit and faith have delivered him from the trammels of life on earth. His greatness seems to increase as we penetrate deeper into his being; and never is his face more expressive than it is in death.

![]()

TRAGEDY OF HIS LIFE

Non vi si pensa quanto sangue costa.

DANTE

As I have already said, the first feeling we are aware of as we approach Dostoeffsky is one of repulsion: but this is followed by a realization of his greatness. His fate, too, at first sight appears both terrible and commonplace; it seems to corroborate the message of his face, to be peasantlike and ordinary. At the outset we cannot but deem his life one long and senseless martyrdom. Poverty robbed him of the sweetness of youth and the peaceful security of old age; pain bored into his vitals and privation wasted his frame; his limbs twitched under the impact of his glowing nerves; his passions were ceaselessly fanned by gusts of desire. No torment is spared him; he escapes no martyrdom. The Erinyes seem to hunt him with remorseless enmity. Yet when we look back upon his life we realize that fate was harsh because something perdurable had to be hammered out of this mortal, that fate made use of violence because it had to overpower a force as mighty as itself. Dostoeffsky did not tread the smooth highway along which other great writers of the nineteenth century were allowed to travel; he was the sport of destiny, the antagonist of a god whose caprice it was to measure forces with the strongest. We must go back to the annals of the Old Testament, to the days of the heroes, before we can find anything comparable to Dostoeffsky’s lot. There is nothing modern about it, nor is there any trace of middle-class comforts and amenities in the story of his pilgrimage. He has, like Jacob, to wrestle with the angel of the Lord; he has, like Job, to rebel against God even while abasing himself before the Eternal. He is never allowed to be sure of himself, never granted a leisure hour, for he must always be aware of the presence of the Almighty who chastens him in sign of loving kindness. Not for a moment may he rest in peace and happiness, for the road upon which he travels leads away into the world without end. It would seem, at times, as if the genii that governed his life had relented, and were about to permit the victim of their wrath to amble quietly along the common highway; but ere he sets foot upon it and can rub shoulders with his fellow-mortals, the hand of the avenger is upon him, thrusting him back into the burning bush. He is raised aloft, only that he may fall the deeper into the pit: thus shall he learn the extremes of ecstasy and of despair. He is caught up to the highest altitudes of hope where weaker vessels perish in voluptuousness, and cast down into the abyss of passion where others are shattered by suffering. Like Job, once more, he is constantly being crushed at the very moment when he feels most secure; he is bereft of wife and children; he is afflicted with illness, despised and scorned, that he may ceaselessly justify his actions before God, and, by perpetual rebellion and unquenchable hope, bear fresh witness to his undying devotion. It would seem as if, in this lukewarm age, one man had been singled out to testify to the world that titanic possibilities of pleasure and pain are still open to us; this one man was Dostoeffsky, through whose being the mighty Will streamed like a torrent. His poor, sick body might writhe convulsively, his sufferings might be poignantly voiced in a letter now and again; but the momentary revolt was instantly quelled by the spirit and by faith. The mystic in Dostoeffsky, the sage in him, recognized the hand that was afflicting him, and he realized the tragical and terrible meaning of his fate. Through his passion, love was turned to pain: he has tinged his epoch and his universe with the witting ardour of his torment.

Thrice does life swing him aloft, only to toss him down again. He is still quite a young man when fame beckons: his very first book makes his name widely known; but almost at once he sinks back into oblivion, undergoing imprisonment, and penal servitude (katorga) in Siberia. Emerging once more from obscurity, he takes Russia by storm with the publication of The House of the Dead. The tsar sheds tears over the book; Young Russia rallies round him. Dostoeffsky founds a periodical, and his words reach the whole Russian people: some of his great novels appear. Whereupon his material existence suffers shipwreck, he is scourged with debts and worries, and hunted forth from his native land; illness bites into his flesh; he becomes a nomad, wandering through Europe, forgotten of his own people. Then, after years of labour and privation, he rises once more to the surface of the grey waters of poverty and neglect: his speech at the Pushkin festival proves him a supreme master of his craft, and the prophet of his homeland. Henceforward the star of his fame is to set no more. But now another hand is raised to crush him; death deals him the final blow, and it is only round his coffin that the waves of popular enthusiasm surge. Fate has nothing more to ask of him; the cruel though omniscient Will has got all it wants out of him, has extracted the most precious of intellectual fruits: contemptuously, the empty husk of the body is flung on to the dust-heap.

Such wanton cruelty it was which made Dostoeffsky’s life at once a work of art and a tragedy. His achievement as an artist is symbolical of his whole existence, in that it assumes the typical form assumed by his own destiny. We find therein strange coincidences and identities and mysterious reflexions which elude demonstration or explanation. Even his birth was symbolical, for Fedor Mihailovich Dostoeffsky was born in the lodge of a workhouse infirmary. In the first hour, his place in the world is indicated to him: he is to be apart, among the rejected, with the dregs of life; he is to be closely acquainted with suffering, sorrow, and death. Not even at the last (for he died in one of the poorer quarters of Petersburg, in a mean street, and in a little fourth-story room) is he to escape the sordid; during the fifty-nine years of his sojourn on earth he remains on terms of intimacy with misery, poverty, illness, and privation; he never quits the workhouse of life.

The strictness of his upbringing encouraged his inborn tendency to brooding. His first years were spent in the atmosphere of the Moscow workhouse infirmary, where he shared a tiny room with his brother. It seems absurd to speak of “childhood” in his connexion, for everything that is relevant to childhood was excluded in little Fedor’s case. Dostoeffsky himself never mentions this period, for his pride made him unwilling to seek sympathy. A grey blank occupies that portion of his biography where luckier poets’ eyes are filled wth laughing and many-hued visions, with tender memories and sweet regret. Yet we may learn much of the early years by looking into the burning eyes of the children he created in his works. He must have resembled Kolya in The Brothers Karamazoff, the lad whose fanciful imaginings bordered on hallucination, who was filled with a fluctuating desire to become great, and who was swayed by a precocious, yet powerful yearning to outgrow himself and “to suffer for the whole of mankind.” His heart must have been like a chalice brimful and running over with love, but burdened with a hysterical anxiety lest he betray himself, like little Netyoshka. Again, may we not catch a glimpse of Dostoeffsky’s own features in his portrait of Ilyuchka, the son of a drunken captain, who suffered so much shame on account of his poverty-stricken home life, and nevertheless was ever on the alert in defence of his kin?

By the time he stepped forth from this dreary world, his childhood was over and done with. He took refuge in the world of books, that everlasting sanctuary for all those who are dissatisfied and slighted. It is a variegated world, full of perils. He and his brother spent many a night and many a day in reading the same books. Already at that time he was insatiable where his inclinations were concerned, so that even the most innocent impulse was intensified to a vice. Though he is filled with enthusiasm for humanity at large, yet he is morbidly shy and reserved, simultaneously fire and ice, obsessed by a craving for solitude. He gropes aimlessly amid the passions, explores every by-way of the cellarage wherein his spirit dwells during these youthful years, always alone and filled with disgust in the midst of pleasure, always oppressed by a sense of guilt while tasting of happiness, always with grimly set lips. He spends a few dull years in the School of Engineers; they are dull because he makes no friends—and because he is kept on short allowance among those who have money to burn. Like the heroes in his books, he lives the life of a hermit, passing his days adreaming, deep in meditation, his only company the secret burden of thought and of speculation. At present he sees no way opening up as an outlet to his ambition; he is on the watch over himself and sits in his lair incubating his powers. With mingled voluptuousness and horror, he feels that they are germinating, deep down; he loves them, and at the same time he fears them; he is afraid even to move lest he should mar these obscure and delicate processes. For several years he remains in this larval state of solitude and silence; he becomes hypochondriacal, is seized with a mystical longing for death, is often over-whelmed with terror of the outer world and of himself, and shudders as he contemplates the chaos in his own breast. In order to provide for his immediate wants, he spends the nights translating Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet and Schiller’s Don Carlos; characteristically enough, the money thus earned is soon spent in the satisfaction of contradictory inclinations: almsgiving and excesses. From the murky squalor of these days something slowly emerges and takes definite shape; at last, out of the visionary and crowded state of alternating anxiety and ecstasy, there is born the first fruit of his imagination, the novel, Poor Folk.

It was in 1844, when the author was twenty-four years of age, that this masterly study was written, a study of human nature by the most lonesome of men, composed “with passionate ardour, nay, almost with tears.” His poverty, the fountain-head of his humiliation, was responsible for its genesis; his greatest asset, love of suffering, an endless capacity for suffering with others, gave the work its blessing. Dostoeffsky contemplated the pages uneasily. He suspected they contained a question asked of fate, the answer to which might mean something decisive to his career. It was only after mature reflection that he made up his mind to submit the manuscript...