- 430 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Theories Of Memory

About this book

This is a collection of chapters by some of the most influential memory researchers. Chapters focus on a wide range of key areas of research. The main emphasis throughout the book is on theoretical issues and how they relate to existing empirical work. The contributions reveal that memory continues to be an important research area and they provide a state-of- the-art perspective on this central aspect of cognitive psychology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Theories Of Memory by Alan F. Collins,Martin A. Conway,Peter E. Morris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter one

The Practice of Memory

Susan E. Gathercole, Martin A. Conway, Alan F. Collins and Peter E. Morris

Memory Research Unit; Department of Psychology, Lancaster University, UK

Introduction

The papers at the International Conference on Memory, held at Lancaster, England (1991, July) provided an international showcase of current research in human memory. Most of the key traditions within contemporary memory research were represented at the meeting. Specialised sessions were held on major theoretical areas such as implicit memory, working memory, and autobiographical memory, and in leading areas of applied memory research, too—symposia topics included ageing, emotion, and viral infections. Both during and between sessions, there was lively and productive crosstalk between memory researchers from a range of backgrounds: neuropsychologists, developmental psychologists, and social psychologists, as well as cognitive psychologists.

In the course of organising the programme for the conference, we started discussing our own folk beliefs about the practice of memory research. One such belief shared by a number of us was that some categories of memory research (such as neuropsychological and clinical studies, and investigations of older subjects) were more readily fundable than others (in particular, mainstream cognitive psychology), mainly because it is easier to convince funding bodies about the practical applications that would follow from such work. Another belief was that some areas of memory research were much more time-consuming than others—work with children, with patients, and with other populations of special interest to psychologists seems to be especially demanding of subject recruitment and testing time.

The Survey

In the midst of this discussion, we realised that the conference provided a unique opportunity to survey such issues relating to the practice of memory research. There were 179 papers on memory presented at the conference, with participants drawn from wide ranges of both geographical locations and academic traditions. The participants were all active researchers who wished to communicate their work in an international forum. This provided the ideal sample of successful and committed researchers to whom we could address questions about the practice of memory research.

We designed a questionnaire, which was sent to each of the 162 participants who had presented empirical data in their conference paper. Each paper was classified according to the research area signalled in the published abstract. The categories were experimental, neuropsychological, developmental, ageing, and special populations. The special population category was notably heterogeneous, and included studies exploring “super” populations (such as scientists, Mastermind contestants, chess players, and a mnemonist who had committed to memory the Blackpool telephone directory) as well as “deficit” groups (such as dyslexic children, depressed patients, and individuals who were HIV positive). Conference papers were also classified according to the country in which the research was conducted.

The first three questions on the questionnaire focused on funding: researchers were asked if they had received funding for this research from funding bodies other than their own institution and, if so, from whom and how much. The next question asked for an estimate of how many hours were spent in collecting data. Participants were also asked who collected the data (was it the author, a collaborator, a research assistant, a graduate student, an undergraduate student, or someone else?) Finally, an optional and more open-ended question was included, which asked participants to identify any major practical difficulties they encountered in the course of conducting their research.

The Replies

A total of 118 participants completed and returned the questionnaire (a response rate of 73%). Faced with the pile of completed questionnaires ready to be analysed it became clear to us that we had just conducted a research project within the everyday memory tradition (Neisser, 1978). It fitted the bill almost perfectly (the main imperfection being that it wasn’t a study of memory in the usual meaning of the word). On the one hand, it was a unique opportunity (the first international conference to have been devoted to memory) to study a natural event. The questions asked were of significance for human behaviour (if cognitive psychologists/developmentalists/neuropsychologists get more funding than us, then we may change research area). Also, and we think that this next criterion may well explain much of the popularity of everyday memory research, it was intrinsically interesting to researchers.

On the other hand, unfortunately, this study also inherited many of the attendant limitations of everyday memory research (Banaji & Crowder, 1989). The subjects were a doubly self-selected sample (first, in electing to present a paper at the conference and, second, in completing the questionnaire). The tasks involved were unnatural (just how do you estimate how many hours were spent in data collection when your research assistant did it?) Finally, researchers were not randomly allocated to the natural categories (of research area, and of nationality of the research institution), which, as a consequence, were notably non-random.

Despite these largely unavoidable limitations to the study, this survey offers a unique natural history of memory research. Its merits, we hope, outweigh its failings.

Funding and Data Collection

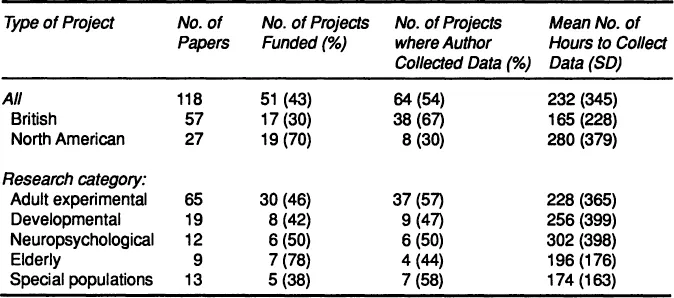

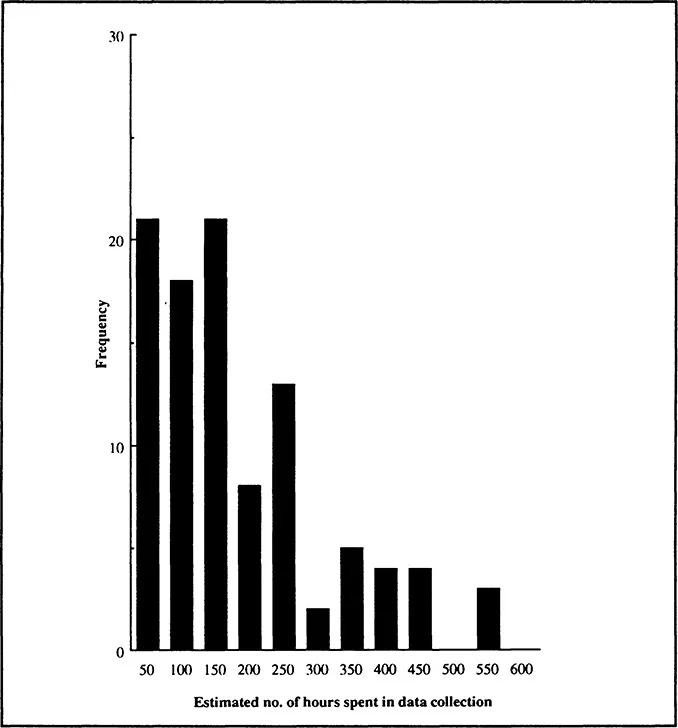

Table 1.1 summarises the quantitative data from the questionnaires. Consider first the top row of the table. Of the 118 conference papers, just under half of them (43%) were funded by independent funding bodies (graduate students were not included in this category), and the author was involved in data collection on just over half of the projects (54%). On average, collection of the data reported in a conference paper took 232 hours. There was, however, a high degree of variability in these estimates (SD=345). A frequency distribution of hours taken to collect the data is shown in Fig. 1.1, which reveals a strong negative skew towards relatively low estimates of time: 66% of the estimates were less than 300 hours. A further 10 estimates (8.5%) were beyond the 600 hours range shown in Fig. 1.1. At the extreme, in two cases the researchers estimated times in excess of 2000 hours.

These quantitative measures were also subclassified in two ways: by the country in which the research was conducted, and by research area. Comparisons between the profiles of research papers across countries were restricted to two nations only, due to the small numbers of contributors from other countries. There were 57 researchers from Britain, and 27 researchers from North America (we included data from the Canadian delegates in this category). The participants from these two countries differed significantly in terms of independent funding: there were a greater proportion of funded projects from North America (70%) than from Britain (30%, P < 0.001 by chi-square). They also differed to a corresponding degree in the proportion of projects in which the authors were involved in data collection: whereas 67% of the researchers from Britain collected data, only 30% of the North American researchers did (P < 0.005 by chi-square). Of course, these two measures would be expected to bear a fairly direct reciprocal relationship of this kind: funding typically provides the research assistance necessary to release the author from the need to collect data. In terms of time spent collecting data, the British mean of 165 hours was considerably lower than the mean of 280 hours spent by the North American teams. Variances, however, were high and this difference was not significant.

TABLE 1.1

Summary of Quantitative Data from the Memory Survey Questionnaire

Summary of Quantitative Data from the Memory Survey Questionnaire

It is tempting to interpret these national differences in terms of fundamental differences in the practice of memory research between Britain and North America; perhaps memory research is more readily fundable in North America and, as a consequence, researchers have to spend less of their time collecting the data. British researchers have often been known to air such views. The selection biases inherent in these data, however, are just too strong to support such generalisations. The resources required to attend the conference were obviously much greater for North American than for home researchers; the North Americans who did participate in the conference were therefore more likely to have substantial research funding upon which they could draw to support their attendance. For most British researchers, in contrast, the cost of attending the conference was within the reach of the standard departmental travel allocation. It therefore seems inevitable that of the contributors to ICOM, those with furthest to travel would be more likely to have external research funding.

FIG. 1.1 Frequency distribution of number of hours estimated to be spend in data collection.

These selection problems do not, however, apply to the classification of questionnaire responses by research area. The lower panel of Table 1.1 provides a breakdown of the quantitative estimates as a function of the research category. Note that the majority of the papers were classified as “adult experimental” (59%); we use this description here to refer to research using normal adult subject populations rather than to signify particular kinds of methodology. Of the remaining papers, 14% were developmental (involving the study of children), 8% were neuropsychological (involving brain-damaged patients), 8% studied elderly subjects, and 10% involved testing special populations.

The proportion of projects funded within each of these research categories did differ, although not to a sufficient extent to yield significant differences with these small sample sizes. Whereas less than half of the conference papers classified as experimental, developmental, and special populations were supported by external funds, two-thirds of the neuropsychological projects and the projects on elderly populations were funded. However, 67% of the authors of neuropsychological projects nonetheless collected data themselves (compared with 53% for experimental and developmental projects, and 58% for projects on special populations). In the studies of the elderly, though, the relatively high proportion of funded projects was mirrored by a relatively low proportion of authors involved in data collection (40%).

Although they are interesting, these quantitative data defy strong interpretation as a consequence of the sizeable variations in numbers of researchers contributing to the different categories. They are, however, at least suggestive that there are genuinely different profiles of research practice associated with projects using neuropsychological patients and elderly subjects, compared with the more common research projects using normal adults as experimental subjects.

Practical Difficulties in Conducting the Research

Substantial and significant differences in research practice between the research categories were revealed in the qualitative analysis of the optional final question. Researchers were asked: “What were the major practical difficulties which you encountered while conducting the research reported in your paper?” No difficulties were noted in 16% of the developmental projects and 17% of the experimental projects. This “satisfaction rate” increased to 25% for neuropsychological projects, 31% for research with special populations, and 33% for work with the elderly.

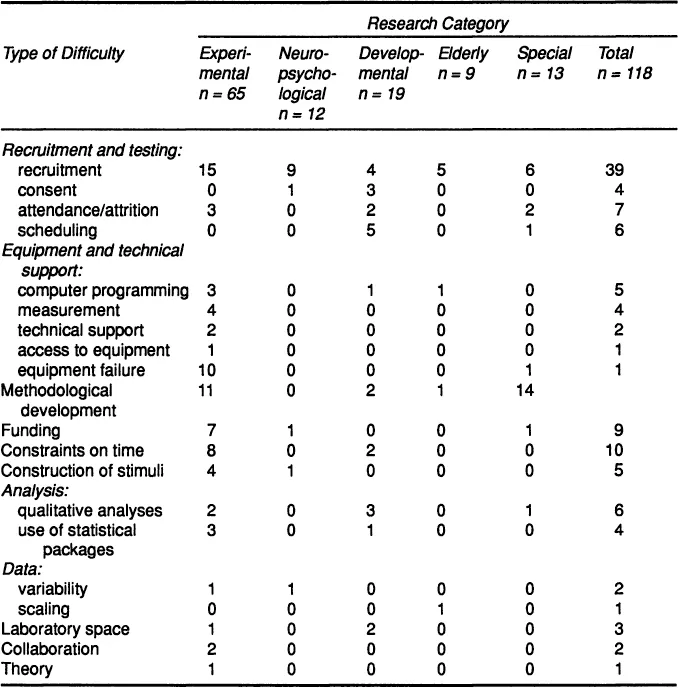

Much richer information concerning the nature of the differences between memory research in these various research categories was provided by classifying the difficulties identified by respondents. A total of 126 difficulties were generated. Table 1.2 provides a league table of these items, classified into the following categories (listed in descending order of frequency—problems relating to: (1) access to subject populations; (2) equipment and technical support; (3) methodological development; (4) funding; (5) constraints on time; (6) construction of stimuli; (7) analysis; (8) data; (9) laboratory space; (10) theory.

TABLE 1.2

Classification of Difficulties Encountered by Memory Researchers, by Research Category

Classification of Difficulties Encountered by Memory Researchers, by Research Category

The largest area of difficulty concerned access to subject populations, totalling 56 responses. There were significant differences in the proportions of problems relating to subject access across the research categories. Access problems were more frequent for both neuropsychological and developmental projects than for experimental papers (P < 0.001, and P < 0.005 by chi-square, respectively). These differences seem intuitively plausible: whereas researchers using normal adults as experimental subjects usually have easy access to either undergraduate classes or subject panels, the procedures involved in selecting and accessing patients and children are considerably less straightforward.

What other differences were there across research categories? In order to obtain a satisfaction index independent of access difficulties, the respondents were each classified into one of two exclusive categories: those who identified difficulties other than those relating to access, and those identifying no other difficulties. The percentages of researchers who listed non-access problems were 66% for the experimental projects, 53% for the developmental projects, and 44% for the work with elderly subjects. In contrast, only 17% of researchers directing neuropsychological projects and 10% of researchers working with special populations encountered non-access problems. A number of differences between groups on these measures were found: non-access problems were significantly more frequent for both experimental and developmental projects than for both neuropsychological and special population projects (P < 0.05 in all cases by chi-square).

So it appears that if problems arising from access to subjects are put aside, fewer difficulties are encountered in the course of neuropsychological research than in experimental research with normal adult subjects. Developmental researchers, however, encounter more extensive subject access problems than experimental researchers, in addition to a comparable rate of difficulties unrelated to access. In fact, the frequency of difficulties arising from statistical analysis was significantly greater for researchers on developmental projects than for those on experimental projects (P < 0.05, by chi-square). Psychologists working with special populations, though, appeared to encounter the least unfavourable circumstances. Perhaps surprisingly, they did not have a notably high rate of access problems, and the proportion of difficulties unrelated to access was the lowest observed in all the five research categories.

The Implications

What does all this tell us about the practice of memory? Quite a few things, we think, all of which demonstrate that a lot of work goes into a conference paper. There are many problems faced by the successful memory researcher: time and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1. The Practice of Memory

- 2. Working Memory and Conscious Awareness

- 3. Flexibility, Structure, and Linguistic Vagary in Concepts: Manifestations of a Compositional System of Perceptual Symbols

- 4. The Structure of Autobiographical Memory

- 5. Systems and Principles in Memory Theory: Another Critique of Pure Memory

- 6. Recognising and Remembering

- 7. Developmental Changes in Short-term Memory: A Revised Working Memory Perspective

- 8. Imagery and Classification

- 9. MEM: Memory Subsystems as Processes

- 10. Problems and Solutions In Memory and Cognition

- 11. Is Lexical Processing just an “ACT”?

- 12. Monitoring and Gain Control in an Episodic Memory Model: Relation to the P300 Event-related Potential

- 13. Explaining the Emergence of Autobiographical Memory in Early Childhood

- 14. Understanding Implicit Memory: A Cognitive Neuroscience Approach

- Author index

- Subject index