![]()

The Concept of Control

Not so very long ago, Ellen Perkins took her 7-year-old daughter, Hannah, dress shopping for a special occasion. They started out at a store near their house. Hannah looked adorable in the pink chiffon she tried on, but Hannah hated pink. Her mother was exasperated but agreed to go to the mall to look some more. The problem was that Mrs. Perkins was already strapped for time. The mall was 30 minutes away. When they arrived at the mall, Mrs. Perkins decided to try to check one more thing off her list. Hannah’s bangs were in her eyes. “Let’s get those bangs trimmed right here,” Mrs. Perkins said.

Hannah refused. “No! I don’t trust those haircutters!”

Mrs. Perkins, already stressed, reacted: “If you don’t get your hair cut, then we’ll go home right now. You won’t get a dress.”

“Fine,” Hannah said.

Not getting what she wanted, Mrs. Perkins decided to up the ante of control. “If you don’t get your bangs cut, then I’m not going to get the present you want to get for your friend, and no one else will buy it either.”

Hannah started to cry.

In this case, the increasing pressure and force applied by Mrs. Perkins signals control, but just what does it mean to be controlling? In this chapter I explore the concept of control. I discuss terms such as psychological control, autocratic parenting, and the authoritarian style, and I contrast those styles with psychological autonomy, democratic parenting, and the authoritative style. On the basis of this work, I differentiate the concept of being “in control” from that of being “controlling.” I will also contrast the ideas of involvement and control. One question I explore later is: When does involvement become controlling?

PARENTING DIMENSIONS

The literature on parenting is replete with a sometimes-confusing array of terms to describe parenting types and dimensions. Researchers have used terms such as responsive parenting, sensitive parenting, democratic versus autocratic, and restrictive versus nonrestrictive. Trying to determine what makes for “good” parenting means wading through these terms—and more. Often the meaning is unclear from the label and readers have to judge a particular researcher’s usage and intent and evaluate the way in which parenting dimensions are measured. The task is complicated even more by the fact that the same term can have different meanings to different researchers.

The terminology mire can be daunting. It can appear that no two researchers are studying the same concepts, much less yielding consistent findings. However, when parenting questionnaires, made up of multiple self-report parenting items, or ratings of parents drawn from observations, have been factor analyzed during the last 35 years, two dimensions consistently emerge. Regardless of what they are called, they appear to be reliably tapping two key parenting dimensions.

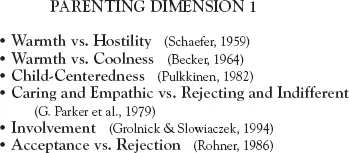

The first dimension has been variously called parental warmth, acceptance, responsivity, and child-centeredness. Figure 1.1 presents a list of some of these terms. In general the dimension refers to parents providing emotional and material resources to their children. In my own work I have referred to this dimension as involvement.

Earl Schaefer (1959) suggested that parents could be placed along a warmth–hostility dimension, with ratings of high affection, positive reinforcement, and sensitivity to the child’s needs and desires at one end and rejection and hostility at the other. Alfred Baldwin (1955) and Wesley Becker (1964) found evidence of a dimension that ranged from warmth to coolness. Lea Pulkkinen (1982) distinguished parent-centered versus child-centered parenting, and G. Parker, Tupling, and Brown (1979), using the Parent Bonding Instrument, identified caring and empathic parenting versus rejecting or indifferent parenting. Diana Baumrind’s (1967) typological scheme identifies authoritative parents as warm and accepting and authoritarian parents as cool and aloof. Researchers who hold an attachment perspective posit that children develop secure attachments to their caregivers through available, responsive parenting (Sroufe & Waters, 1977).

Evidence for the underlying correspondence of these differently named constructs comes from the fact that each construct predicts similar qualities in children. Warmth was found to be associated with children’s higher self-esteem in classic studies by Coopersmith (1967). Parental involvement has been linked to children’s self-esteem (Loeb, Horst, & Horton, 1980) as well as to higher levels of achievement and motivation and lower levels of delinquency and aggression (Hatfield, Ferguson, & Alpert, 1967). I present these facts without elaboration for now, but later I argue that the effects of warmth and involvement depend on other dimensions. Nonetheless, at this point we can conclude that warm, responsive, and involved caretaking yields positive effects.

FIG. 1.1. Parenting Dimension 1.

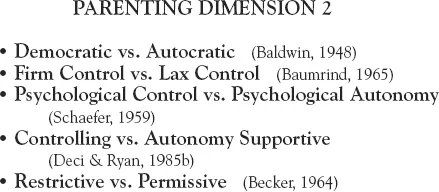

The second dimension that emerges in the majority of parenting studies is far more perplexing than involvement. What unites this second dimension as it emerges across various studies is its relation to control. Descriptions of this dimension include controlling versus permissive, firm control versus lax control, psychological control versus psychological autonomy, restrictive versus permissive, and controlling versus autonomy supportive (see Fig. 1.2 for a list of some of these terms). How have different researchers understood this dimension?

EARLY CONCEPTS OF CONTROL

Baldwin’s (1948) groundbreaking investigation of child rearing conducted at the Fels Research Institute in the 1940s was one of the first to examine systematically the idea of parental control. Baldwin interviewed the parents of 67 children, beginning when the children were 4 years old then observing the parents and children every 6 months afterward. On the basis of the interviews and observations he rated children and parents on a number of dimensions, including sensitivity, impatience, and affectionateness. Factor analysis of the ratings of parents yielded two general factors: Control and Democracy. Control, as defined by Baldwin, “emphasizes the existence of restrictions upon behavior which are clearly conveyed to the child” (p. 130). Democracy involved high levels of verbal contact between parent and child and openness of communication. In democratic parenting, polices are arrived at by mutual agreement, reasons are given for disciplinary actions, and the child’s input in parenting decisions is sought when possible. Control and Democracy were positively correlated.

FIG. 1.2. Parenting Dimension 2.

Thus in Baldwin’s (1948) study, control refers to the limits, rules, and restrictions placed on children’s behavior. For Baldwin, control was positive. However, although control and democracy tended to be correlated, it was possible to have control within the context of democratic or more autocratic parenting.

What effects do these parenting characteristics have on children? Keeping control constant, Baldwin (1948) found that democracy produces an aggressive, fearless, and playful child who tends to be a leader but also who is cruel to his or her peers. With democracy held constant, control decreases quarrelsomeness, negativism, and disobedience. Occurring together, control and lack of democracy create a quiet, well-behaved child who is low in creativity. The best outcomes were observed in homes in which there was a great deal of interaction between parents and children, along with democracy.

Becker (1964) proposed two factors of parenting: restrictiveness versus permissiveness and warmth versus hostility. He characterized the restrictive end as having “restrictions and strict enforcement of demands in the areas of sex play, modesty behavior, table manners, toilet training, neatness, orderliness, care of household furniture, noise, obedience, aggression to siblings, aggression to peers, and aggression to parents” (p. 174). The permissive end included fewer restrictions, and the enforcement was less firm. Becker crossed the two dimensions to yield four types of parents: warm–restrictive, warm–permissive, hostile–restrictive, and hostile–permissive. He determined that the warm–permissive quadrant contained the most positive characteristics.

How can one reconcile the fact that in Baldwin’s (1948) work control was positive, whereas in Becker’s (1964) work permissiveness was more desirable? One way is to note that in Becker’s work restrictiveness included two issues: the degree to which rules and regulations existed and the degree to which these were “strictly reinforced.” It is likely that Becker’s negative findings reflect the fact that he was conflating two dimensions, one related to having rules, and the other to administering those rules in a controlling (or undemocratic) manner. The fact that the dimension picked up rules conveyed in a controlling manner was likely responsible for the negative findings. By contrast, Baldwin separated out having rules and limits from parents’ general styles of democratic or undemocratic parenting.

BAUMRIND’S TYPOLOGICAL CONCEPTUALIZATION

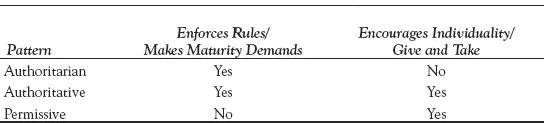

In her highly influential early work on parental authority with children Diana Baumrind (Baumrind, 1967, 1977) took a typological approach, dividing parents into different categories. She initially described three patterns of parental authority based on a cluster analysis of 50 behavior ratings of parent interviews and home observations: permissive, authoritarian, and authoritative (see Table 1.1). The authoritarian parent attempts to shape, control, and evaluate the child using set standards. He or she values obedience first and foremost and uses forceful measures to inculcate desired behavior. This parent does not encourage verbal give and take but prefers that the child accept his or her word for what is right. This type of parent tends to enforce rules firmly, confronts and sanctions negative behavior on the part of the child, and discourages independence and individuality. He or she also tends to be rejecting, although Baumrind did identify some authoritarian parents who were less so.

The authoritative parent, on the other hand, attempts to direct the child in a rational, issue-oriented manner. He or she encourages verbal give and take, provides reasons for her decisions, and solicits the child’s opinions. This parent, like the authoritarian parent, firmly enforces rules and is willing to confront misbehavior, yet, in contrast, he or she encourages independence and individuality.

TABLE 1.1

Baumrind’s Patterns of Child Rearing

The permissive parent is nonpunitive, accepts the child’s impulses, and is unlikely to intervene by curbing them. He or she also responds to the child in an affirmative way. This parent imposes few demands, and thus the child has few household responsibilities. The permissive parent does not enforce rules firmly and tends to ignore or excuse misbehavior but, like the authoritative parent, encourages independence and individuality.

Baumrind and Black (1967) examined the consequences of these parenting patterns for children in preschool. In a follow-up study, Baumrind (1977) evaluated the children when they were 8 and 9 years old. She found that the preschool children of authoritarian parents were moody and unhappy, relatively aimless, and did not get along well with other children. By ages 8 and 9, these same children, particularly the boys, were low in achievement motivation and social assertion.

In contrast, the preschool children of authoritative parents were energetic, socially outgoing, and independent. The 8- and 9-year-olds were highly achievement oriented, friendly, and socially responsive.

Finally, the preschool children of permissive parents lacked impulse control and were self-centered and low in achievement motivation. By ages 8 and 9 they were described as low in both social and cognitive competence.

Using this same sample of parents and children, Baumrind (1996) later reframed her views of parenting. She used a two-dimensional conceptualization, that included demandingness and responsiveness. She defined demandingness as the “claims parents make on the child to become integrated into the family whole by making maturity demands, supervision, disciplinary efforts and willingness to confront the child who disobeys” (p. 411). Thus, demanding parents supervise and monitor their children and are willing to openly confront them when there is a disagreement or wrongdoing. They expect children to perform up to their abilities and to contribute to the family. She defined responsiveness as the extent to which parents “intentionally foster individuality, self-regulation, and self-assertion by being attuned, supportive and acquiescent to the children’s special needs and desires” (p. 410). The responsivity dimension thus combined warm supportiveness with valuing and promoting individuality through open give and take.

In Baumrind’s (1991a) scheme, parents can be divided into four types: authoritative (demanding and responsive), authoritarian (demanding but not responsive), permissive (more responsive than demanding), and rejecting/neglecting (neither responsive nor demanding). When Baumrind examined how children of parents placed into these categories fared, she found the best outcomes for children of authoritative parents and the worst for the rejecting/neglecting parents.

When the children were approximately 15 years old, Baumrind (1991b) conducted another follow-up, this time dividing the parents into six types. She further differentiated the demanding–responsive parents in a way that was particularly relevant to parenting in adolescence. First, she distinguished parents who were authoritative (demanding and responsive) from those who were directive (valuing conformity above individuality and high in demandingness). The directive parents were further divided into intrusive and nonintrusive types (authoritarian–directive and nonauthoritarian directive, respectively). There were two types of permissive parents: Those who were highly committed to their children were labeled democratic, and those who were not as committed were labeled nondirective. A good enough group was characterized by medium low to medium high demandingness but only moderate supportiveness. Finally, an unengaged group did not structure or monitor their children and was highly disorganized.

Comparing the children of these different groups, Baumrind (1991b) found that adolescents of authoritative and democratic parents were high in competence, individuation, maturity, achievement motivation, and self-regulation. Children of directive parents lacked individuation and autonomy and were rated high in seeking adult a...