![]()

1

Introduction

‘Oui, c’est l’Europe, depuis l’Atlantique jusqu’à l’Oural, c’est l’Europe, c’est tout l’Europe, qui décidera du destin du monde.’ ‘Yes, it is Europe, from the Atlantic to the Urals, it is Europe, it is the whole of Europe, that will decide the fate of the world.’

(Charles de Gaulle, President of France, 23 November 1959, Strasbourg)

This book is intended to serve as a basis for the study of the European Union (EU) within a broader European and global context. Since its foundation as the European Communities (EC) in the 1950s the EU has grown into a supranational entity rivalled in its economic scale only by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In the mid-1990s the future of the EU has been very much under debate in a fast-changing continent, and with increasing pressures upon it from other regions of the developed and developing worlds. The geographical approach is used in this book to analyse and to evaluate the major economic, social and political aspects of the EU with particular reference to spatial issues and problems. In order to establish the framework for the book it is appropriate first to put the EU in its European and global contexts.

Membership of the EU is explicitly open only to countries located in Europe. At least in principle the policy of the EU is to welcome eligible countries to membership. It is therefore necessary here to note the traditional or conventional extent and limits of the continent of Europe. General de Gaulle (cited at the start of the chapter) was prophetic when he emphasised the continent of Europe as a whole and as a single entity, although he overlooked the fact that Russia extends eastwards far beyond the Ural Mountains, indeed to the Pacific coast. However, only since the break-up of the Soviet bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA), in 1990, and of the Soviet Union itself in 1991 has the definition of the limits of Europe been a matter of more than academic interest to the citizens of the EU.

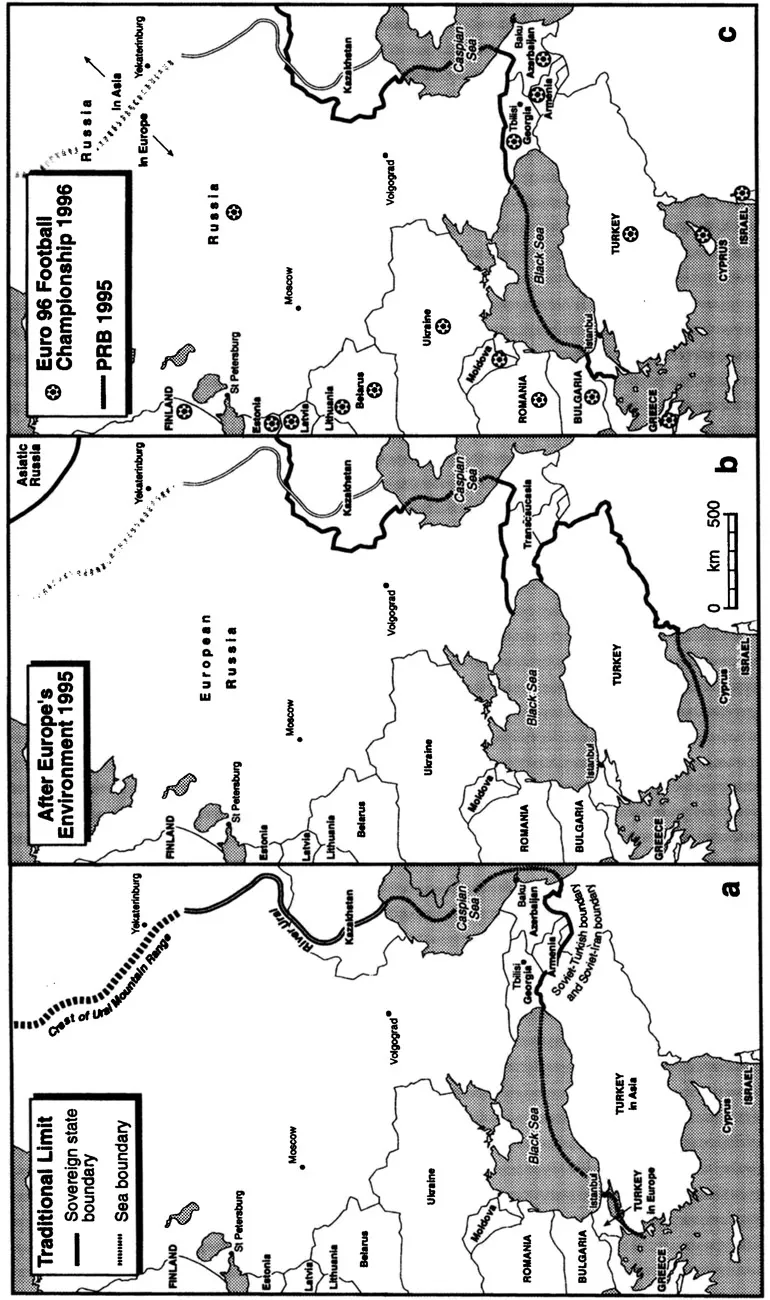

Europe conventionally extends eastwards to the Ural Mountains of Russia, the Ural River and the Caspian Sea. In the south it is separated from Africa by the Mediterranean, and from Asia by the Bosphorus, the Black Sea and the mountains and rivers south of Transcaucasia. Figure 1.1 shows recent variations on the theme of Europe’s limits. These limits are traditionally associated with physical features, but they do not run through barriers of great note politically, militarily or culturally.

Early in the fifteenth century the Chinese briefly explored and occupied parts of southeast and south Asia beyond the traditional units of their Empire. It was the Europeans, however,

Figure 1.1 Different definitions of the limits of Europe

Map a Traditional limit as described in the text

Map b Stanners and Bourdeau (1995) in Europe’s Environment include the whole of the Ural economic planning region of the former USSR, which extends both sides of the crest of the Ural Mountains. They exclude a small part of Kazakhstan, between its western boundary and the Ural River, and all three Transcaucasian Republics of the former USSR, but include the whole of Turkey

Map c shows how the latest Population Reference Bureau’s World Population Data Sheet puts the whole of Russia into Europe but excludes Transcaucasia and Turkey. The football symbols show all the countries in the eastern part of Europe that participated in the EURO 96 Football Championship, with Turkey, Cyprus and Israel deemed to be part of Europe for the purposes of the Championship

who, late in the fifteenth century, began to conquer and colonise lands beyond the limits of their continent. Thus Europe became the first region of the world to establish its influence on a global scale. In 1494 the Pope divided the world beyond Europe between Spain and Portugal in the Treaty of Tordesillas. Christian Europe thus effectively gave itself a mandate to conquer anywhere in the world.

The empires of the Western European countries continued to grow in some parts of the world into the twentieth century, but more than 200 years ago they started to disintegrate with the War of American Independence. Such countries of the EU as France, Belgium and the UK have lost most of their colonies over the last few decades. Ties have, however, been maintained through the Lome Convention, linking the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries with the EU by trade and development cooperation agreements. The British Commonwealth and the Francophone Community (which links France with many of its former colonies in Africa) also help to retain ties between the EU and former colonies.

While Spain, Portugal and, subsequently, other Western European countries were acquiring colonies in various parts of the world from the sixteenth century onwards, Russia was expanding in several directions in the eastern half of Europe, and in the seventeenth century it conquered much of what is now Siberia. In the early 1990s the Soviet Union, inheritor of the vast Russian Empire, was in its turn dissolved, and various non-Russian peoples in the Union readily accepted independence. Such a development has particular significance for the EU, since several former Soviet Republics, after achieving independence from Russia in 1991, have been looking towards the European Union for support. At the time of writing, the three Baltic Republics had already applied for EU membership.

Much of Europe is characterised by great physical and cultural diversity. Many cultural features have origins far back in the past. These affect the organisation and expansion of the EU today, whether they are linguistic, religious or political. Until the sixteenth century Europe was frequently the recipient of migrants, technologies and cultural features from Asia and Africa. At times, as when Greek and Roman conquests extended European power into North Africa and southwest Asia, its own influence spread beyond the continent. Most of the invaders of Europe came from the east or southeast, some from North Africa. As noted above, after 1500 the tide turned, and for the next four centuries the influence of a number of European powers extended to many parts of the world with varying degrees of intensity. Only the Ottoman Turks continued to have control over a part of Europe after the middle of the sixteenth century.

While engaged in conquering other parts of the world, during the last five centuries European powers have also frequently been in conflict among themselves both in Europe itself and elsewhere in the world. Since the Second World War, and during the last stages of the disintegration of their empires, Western European countries have come together in entities for cooperation in defence and trade (see the next section). The creation of the supranational bodies of the EU has brought together former rivals and enemies in a completely new situation. In the European Parliament, politicians of similar political views from the 15 Member States of the EU form transnational groups or alliances. The same politicians are regrouped and allocated to delegations, each vested with the care of the Parliament’s relations with the parliament and/or responsible national authorities of a particular country or group of countries elsewhere in the world. Such strange bedfellows would have been unthinkable 60 years ago.

In the present book the EU is considered both as an entity moving, sometimes against historical traditions, towards greater unity, and as a region of the world coming to terms rapidly with a new situation in Europe and likely also to be influenced increasingly by regions outside Europe. Early in the twentieth century, the British geographer Halford Mackinder (1904) argued that future historians might refer to the period 1500—1900 as ‘the Columbian epoch’:

Broadly speaking, we may contrast the Columbian epoch with the age which preceded it, by describing its essential characteristic as the expansion of Europe against almost negligible resistances, whereas mediaeval Christendom was pent into a narrow region and threatened by external barbarism. From the present time forth [1904] we shall again have to deal with a closed political system, and none the less that it will be one of worldwide scope. Every explosion of social forces, instead of being dissipated in a surrounding circuit of unknown space and barbaric chaos, will be sharply re-echoed from the far side of the globe, and weak elements in the political and economic organism of the world will be shattered in consequence.

(Mackinder 1904)

We are now well into Mackinder’s post-Columbian epoch. If his view of the world has turned out to be correct, then in the future Western Europe’s global position may soon be more like its position in the pre-Columbian epoch than it was in the Columbian epoch. From now on there will be pressures from outside: from the USA and Japan to maintain innovative and competitive industry; from Central Europe and the former USSR to help in their economic restructuring; and from the developing countries to be more forthcoming with assistance. There is also growing economic and social pressure from immigrants arriving from both the former CMEA countries and the developing world.

Since the Second World War, a feature of world affairs has been the emergence of supranational blocs in various parts of the world. Apart from the recent demise of the CMEA, the process continues, with much of the economic power of the world concentrated in a few countries or groups of countries, including, for example, the North American Free Trade Agreement, consisting of the USA, Canada and Mexico, with 387 million inhabitants altogether, and the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), with 320 million inhabitants. Whether or not existing supranational entities expand and new ones emerge, it must be appreciated that between 1995 and 2025 the combined population of the developing countries of the world is forecast to grow by about 2.5 billion, adding the population of more than six EUs in that time, the equivalent of a new EU every five years.

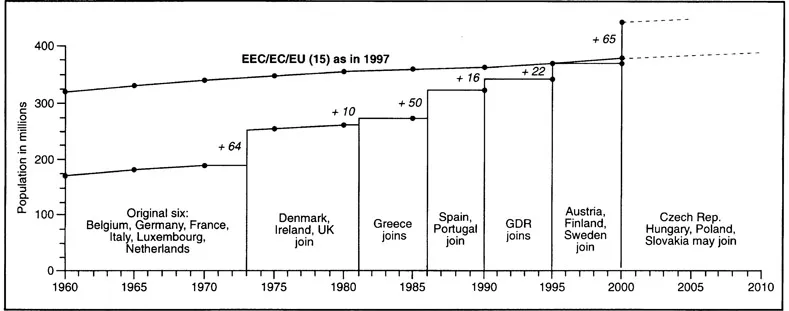

Throughout its history Europe has never formed a single political unit. During several periods, mostly brief, large portions of the territory of Europe have, however, been held, at times loosely, in a single political unit (see Box 1.1). The most recent attempts to bring together a number of separate countries of Europe have been the creation of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, founded in 1949, and of the European Economic Community itself (EEC), founded in 1957. The CMEA was disbanded in 1990 but the EEC, now referred to as the European Union, has expanded since its foundation in a series of ‘steps’ (see Figure 1.2). The European Union has appropriated the name of the continent, although in 1995 its 15 Member States contained only about one-third of the territory of Europe and had less than half of its population.

It would be premature to speculate if and when the whole of Europe will form a single supranational unit, but with regard to two countries in particular the definition of Europe is unclear. The former USSR and Turkey each has territory in both Europe and Asia. Over two-thirds of Russia lies east of the Urals in Asia. Although almost all of the territory of Turkey is in Asia, Turkey could also be considered for EU membership, in spite of its ambivalent position in relation to the two continents, but at the time of writing, the European Commission was not in favour of such a

Figure 1.2 The joining sequence of the current 15 Member States of the EU, showing the population added at each stage of expansion, population growth between stages and the total population of all the present EUR 15 countries since 1960

move. The ‘rule’ that applicants should be in Europe has indeed already been broken with regard to Cyprus, with which negotiations for membership are soon to begin; Cyprus has conventionally been regarded as part of Asia. It would, however, be inappropriate, for example, for New Zealand, South Africa or Uruguay to apply, even though the EU does include several small French Départements d’Outre-Mer, located far from Europe.

Entities in Post-1945 Europe

The Second World War left more than physical scars on a Europe devastated by death and destruction. Citizens and their leaders, stunned by the way in which history had been able to repeat itself, resolved to do their utmost to establish mechanisms and a framework to minimise the risk of armed conflict between European states occurring again. The Conference of Yalta in 1945 established the return of occupied territory, the reaffirmation of most national boundaries and in Central Europe some significant transfers of territory. At the same time, however, in a matter of months after the war ended the clear demarcation was evident in Europe of two separate blocs cre...