![]()

1 Introduction: The history of sociological theory

What is sociology?

Yes, this is another book about sociological theory. And no, this is not the only book about sociological theory that you will need if you want to fully understand the history of and complex debates within that field of inquiry. It is intended to be a first step along the journey to achieving that understanding, nothing more. There are plenty of good books out there which cover sociological theory and go into considerable detail about the many perspectives contained within our discipline of sociology. But one problem I have consistently encountered in all the years I have been teaching theory classes to sociology students is that however good and well written such a book is, it falls on deaf ears if it presumes too much background knowledge. A chapter on functionalism may contain the most elaborate explanation of Talcott Parsons's famous AGIL scheme but this is pointless if the reader is not yet equipped to understand what functionalism even is. A chapter on Marxism may contain a fantastic introduction to Karl Marx's surplus theory of value but such knowledge is lost on a reader who is not yet clear on what a Marxist approach actually involves. And so on, and so forth. . .

It was during the course of a conversation about precisely this problem that an astute commissioning editor uttered those ominous words to me: Why don’t you write the book that solves this problem? This book, the final product of that conversation, is an attempt to introduce sociological theory without all the detail about complicated ideas, major studies, lots of names, but rather through an engagement with eight major traditions and perspectives in the discipline, eight distinctive ways of seeing the world sociologically. Yes, it will introduce you to names. Yes, it will introduce you to a selection of studies. And yes, it will highlight some of those complex ideas. But its purpose is not to provide the definitive account of them – for that, you should consult one of the other, larger texts or, even better, when you feel ready to, check out the original source – but to use them as illustrative of what each perspective actually means, to see how those contributions reflect and form part of a wider tradition or perspective. You, the reader, the student of sociology, are invited to put yourself in the place of an exponent of each of these perspectives, to imagine how they see the world, to do sociology as they would do it. What does it involve to see the world as a Marxist, feminist or interactionist? What tools and concepts are used to make sense of the world?

Sociology is the study of society – and society is comprised of people and the institutions they create to best manage their lives. These institutions include government and politics, the economy, religion, the family, education, work, culture and media, business and organisations, sport and leisure. Each of these institutions serves a purpose in the lives of ‘ordinary’ people, but each of them, like society itself, is driven by inequalities inherent in the social structure – inequalities based on class, status, ‘race’ and ethnicity, gender, age, sexuality, physicality. Sociologists are interested in all of these institutions and inequalities, and their intersections. All of this seems clear enough, surely, but for some commentators, sociology lacks credibility as a discipline. Why should this be the case? Other disciplines, such as biology, psychology and history, don’t seem to suffer from this problem. This is partly, no doubt, because its scope is so broad that it has lost its focus, become nothing more than an unnecessary vocabulary which, along with sibling disciplines and fields such as social anthropology and cultural studies, merely serves to over-complicate common sense. Or so the argument goes. It’s certainly an argument I have heard time and time again, when I have described myself to people as a sociologist.

There can be no doubt that ‘common sense’ provides the intellectual breeding ground for sociological insight. But this is equally true of other disciplines. We can all be amateur historians. Like biologists, we all have bodies, so we know about them, in one capacity or another. Even hard science is to some extent driven by common sense – how many scientific miracles have been first imagined by writers of science fiction? Sociology suffers most because it provides opinions on the things that we live through and in as people, every day of our lives. But the academic study of society is not the same as the everyday understanding of it, any more than the academic study of the body is the same as the physical reality of living with it. Sociology answers to a broad set of questions about how society works, how it evolves, what its constituent parts are and how they relate to one another, and what part people play in its constitution.

To understand the meaning of sociology as a discipline, one first has to understand what is meant by its subject matter, society, the social. When we talk of a social event, we tend to mean one attended by friends bound by something not related to work, but to friendship or family, or perhaps it does involve work colleagues, but it is not in itself a work event. People meet socially. Alternatively, politicians and their constituents talk about social security, or social services. What unites drunken parties and welfare policies? The answer is surprisingly simple. Former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher famously declared that there is ‘no such thing as society’. To her credit, the then Conservative leader used the term ‘society’ appropriately – she wanted to make the point that you, the voter, the individual, the citizen, the consumer, have no responsibility towards others, even those less fortunate than you, no duty to protect anyone other than yourself, and no expectation of support from other people, or from the government. It is down to you to make your way in this world. Thatcher’s dismissal of society is reminiscent of, if ideologically opposed to, an equally accurate theorisation of ‘society’ – the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous suggestion that Hell is others. Living in a world with other people is difficult. It means we cannot get away with what we really want to get away with; we cannot exercise total freedom. We are bound by the fact that we live in a world with other people, and we have to take them into consideration whenever we act. Society is about other people. Sociology is the study of how we live in a world with other people.

Some sociologists limit themselves to the study of particular components of society. Thus, there are sociologists of religion, of education, of the family, and so on. Others try to provide bold theoretical frameworks for the dynamics of nothing less than society itself. Others still make modest comments about human action and behaviour, and grow to be treated as exponents of broader concerns. Sociologists are interested in all of these concerns. They ask ‘grand-scale’ questions about the emergence of societies and the state, and analyse historical social change and large-scale processes such as industrialisation, capitalism, and, more recently, globalisation. But they also ask questions about identity, human agency and the self. They are concerned with culture, our norms and values, what it is produced by and how it impacts on our lives, and how it may carry a particular bias, in the form of ideology. They ask how individuals interact with one another, and how social networks and kinship systems operate. They look at the multiple forms of inequality, social stratification, that exist in societies, including hierarchies of class, gender, ethnicity, and so on. They ask how social order is maintained and who exercises power in societies.

If sociology is about all of these, what makes it distinct? To answer that question, we can turn to one of its most vociferous champions, the nineteenth-century French sociologist Emile Durkheim. Durkheim wrote a famous book in which he compared the suicide rates in different countries. He wanted to show that suicides could be caused by factors external to the individual, factors to do with the norms and values of those societies and the individual’s relationship to them. He was trying to prove a point, that although suicide is one of the most intimate and personal things you could look at, to fully understand it we need to look beyond psychology, the science of the individual mind, and analyse it sociologically. A sociological theory thus looks for factors outside the human mind to explain phenomena like suicide, or educational achievement, or gender inequalities, or kinship systems.

Since Durkheim’s famous defence of sociology as a discipline not reducible to psychology, sociologists have been comfortable with the knowledge that their discipline is in every sense legitimate. Social theory, however, is broader in scope than sociological theory. Consider three disciplines – sociology, psychology and biology. A sociologist and a psychologist may be interested in the same object of study, such as suicide rates. What distinguishes them, as Durkheim rightly claimed, is their choice of explanatory factors. Similarly, psychologists and biologists have often been interested in seeking to explain the same phenomena, such as mental illness, but have done so using quite different methods. It is not inconceivable for biologists and sociologists to overlap as well – both may be interested in the causes of crime (as might the psychologist). But such overlaps are less common. For the most part, sociologists may have engaged in active debates with psychologists, but have left biologists alone. Why, after all, should a sociologist try to explain how the human heart works, or how plants receive their nourishment? Sociology – like any other discipline – has never promised to explain everything! Similarly, why should biologists, whose discipline is equally legitimate and equally modest, seek to understand the reasons for the significance of religion in people’s lives, or the relationship between class and educational achievement?

However, the relationship between the two disciplines is not, actually, so egalitarian. Sociology simply does not have the tools to even try to explain how the heart pumps blood around the body. Biologists, though, do have the tools with which to try to explain, should they feel the need, almost every aspect of human life, even religious meaning or educational achievement. From crude physiological studies of criminality to contemporary popular ideas emerging from the study of genetics, biologists are (at least hypothetically) capable of providing a plausible biological explanation of a social phenomenon. Biology can, then, give us a social – if not a sociological – theory. During the early days of sociology as a discipline, many of its practitioners were doing just this, using biology as a basis for their pseudo-sociology. Back in the nineteenth century, the French physician Paul Broca linked brain size to intelligence in order to show that men are naturally more intelligent than women. An Italian prison doctor, Cesar Lombroso, then claimed he could identify certain physical markings, such as small craniums and pinned-back ears, that distinguished criminals from non-criminals. Examples like this may seem ludicrous to us now, and rightly so, but they do at least serve to highlight the distinctiveness of a sociological approach. Gender inequalities and criminal behaviour are entirely appropriate objects of study for sociologists, but the sociologist would not seek to explain them in terms of such physical characteristics, but rather in the broader institutions, norms and values of wider society. It is not the question which gives sociology its distinctiveness, but the answer.

All of which leaves one question still unanswered. Is sociology a science? Certainly, as we will see, some of its founders certainly thought so. But others, especially more recently, have resisted making such claims. We frequently refer to sociology as a social science, as if this

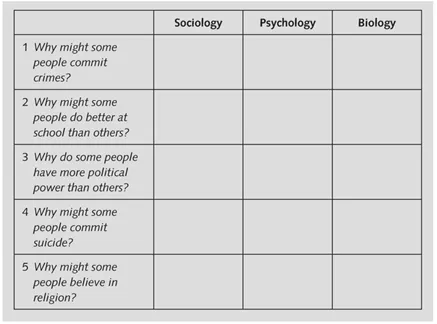

Exercise 1.1 Sociology, psychology and biology

Throughout this book I will be setting you little exercises to try to follow through on the points I want to introduce in the text. In this case, I want you to think about the differences between a sociological, psychological and biological explanation for something. Try to think of one example of each kind of explanation for the five problems listed. I’ve already provided you with some starters in the text above.

carves out a space for it between the ‘real’ sciences and the humanities, but this is perhaps just a way of dodging the question. The truth is, it can be a science, but it doesn’t have to be. For something to be a ‘science’ has nothing to do with how academic subjects are arranged in convenient groups, like faculties at universities. It depends on what the point of the specific research is. If you are studying something with a view to uncovering general laws, to explain, then you are conducting a science. But if you wish to interpret an event, document it, without trying to generalise, then your research fits better under the banner of the ‘humanities’. If you intend for your work to uncover not laws but problems, to serve as a critique of the way things are and inspire change, then it clearly has a more practical, political, activist focus. Over the years, sociology has been all of these things.

A brief history of sociological theory

If this is how we can define sociology, then there is some truth to the suggestion that is often made that the discipline was being practised long before it found itself named and formalised as an academic subject. Many classical philosophers, theologians and political theorists were effectively doing some form of sociology. However, for the sake of this brief introduction, it is probably wise to skip through them and concentrate on the formal origins of the discipline. It was a nineteenth-century Frenchman, Auguste Comte, who first named sociology as a discipline in its own right. Comte set himself the task of establishing a positive science of society. That is to say, he believed it was possible to treat the social world in much the same was as a scientist treats the natural world – to uncover the universal laws that explain why it is as it is. You should note here that Comte’s positivism was very different from those kinds of approach to social behaviour which merely sought to extend existing ways of explaining things to accommodate social action. Someone who, for example, uses biological explanations to tell us why a person commits crimes is hardly doing any sociology! They are trying to explain social phenomena biologically. Comte by contrast wanted to establish sociology as a distinctive science to take its place next to the likes of physics, chemistry and biology. Like them it would utilise scientific method, the use of experimental methods and the development of generalisable laws to explain things, but these would be its own laws. Comte took the idea of society to be a thing in its own right, an object of study capable of being explained in this fashion. It is hardly surprising that, in these early days of the discipline, so much emphasis was placed on establishing sociology as a science – it was a means of legitimising it. Although the pioneering British sociologist Herbert Spencer approached his subject matter in a way radically different from Comte, he also sought to foreground its scientific credentials by utilising developments in evolutionary biological theory and applying them to the question of social change.

Comte and Spencer were responsible for getting sociology off to a start, but the key contributors to its development in the nineteenth century were Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim and Max Weber – the so-called ‘holy trinity’ of founding fathers. These three classical writers differed greatly in so many important ways, and thus effectively paving the foundations for the eclectic range of different sociological schools of thought which were to emerge in the twentieth century, but in a sense, they were all united by a single shared curiosity. Each of them was aware that around them, the world was changing rapidly. The nineteenth century in Europe was the time of the Industrial Revolution. Factories were being established to accommodate the new system of production made possible by new technologies. People were flocking from the villages to where these factories were located, and new urban areas, cities, were emerging as a result. Life in these cities was qualitatively different f...