1

Opportunities and challenges for small economies in global value chains

Rainer Lanz and Hans-Peter Werner1

1 Introduction

Small economies face numerous challenges when trying to buy and sell goods and services at globally competitive prices. Many have a small market size and narrow resource base which limits them from exploiting economies of scale. Many too are islands, are situated in remote locations and are highly vulnerable to natural disasters.

Geographic location, economies of scale, air and seaport infrastructure and adequate logistics and inspection systems are all determinants of the ability of small economies to sell products or services abroad, or from becoming partners in global value chains.

This paper discusses the indicators used to identify small economies (Section 2) and examines how small economies can tap into and benefit from global value chains in goods and services trade (Section 3). It does this by identifying some of the main opportunities and challenges. By analysing a number of statistical indicators and responses to the OECD/WTO Aid-for-Trade questionnaires, the paper identifies issues which small economies must address if they are to successfully tap into value chains. These include trade costs related to transport infrastructure and trade facilitation, standards compliance, access to finance and labour skills.

In the case of goods value chains, the paper analyses the integration of small economies in the agrifood, seafood and textiles and apparel sectors (Section 4). It discusses how small economies have used some of their distinct advantages in these value chains. Value chains in services, especially the importance of the tourism sector for small economies, are examined as are information technology (IT) and business process outsourcing services, especially for remote small economies (Section 5).

Trade policy experiences with value chains are also examined and put in a historical context (Section 6). In this regard, the paper looks back some 40 years to examine how the understanding of value chains has evolved and what policy options are available to small economies. Challenges with upgrading and diversification are discussed as well as the role of imports for export competitiveness.

2 Small economies

The size of countries can be measured by different indicators. Population size is often used for this purpose.

The Commonwealth Secretariat uses a cut-off population point of 1.5 million in its definition of small states and includes non-island states as well as a few states with a population over 1.5 million on the assumption that these share similar characteristics with the smaller countries,2 The World Bank also defines small states as those with a population of 1.5 million or smaller.3

The United Nations lists 37 UN members as small island developing states (SIDS)4, while UNCTAD uses more strict criteria for defining SIDS, and for analytical purposes, proposes a list of 29 SIDS.5 Population size is here again used as a main criterion for defining small country size.

The WTO has no official definition for small economies. However, in trade negotiations during the Doha Round, the size of trade flows had been the defining criteria of whether countries would be eligible to use flexibilities foreseen for small economies (WTO, 2017). For example, the Revised Draft Modalities for Agriculture describe a small economy as one whose average share for the period 1999–2004 did not exceed (a) 0.16 of world merchandise trade; (b) 0.10% of world non-agricultural market access (NAMA) trade; and (c) 0.40% of world agricultural trade.

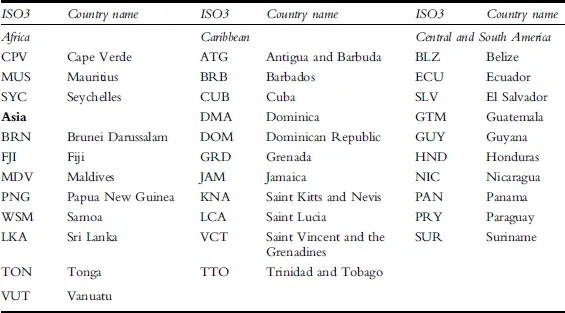

While the Agriculture Draft Modalities list 45 countries as meeting the above criteria, this study includes the 32 small economies which have been most active under the WTO’s Work Programme on Small Economies since its establishment in 2002 (Table 1.1). It should be noted that since trade, and not population or geography, is used as criterion, several small economies covered in this chapter do not meet other criteria discussed above. For instance, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Papua New Guinea, and Sri Lanka have populations larger than 1.5 million, while Central and South American countries are not islands.

Table 1.1 Small economies included in the analysis

3 Opportunities and challenges

One of the most important changes in the nature of international trade has been the growing inter-connectedness of production processes across many countries, with each country specializing in a particular stage of a good’s production. In the trade literature, these processes are referred to as global supply chains, global value chains, international production networks, vertical specialization, offshore outsourcing and production fragmentation. For the sake of clarity, this paper will refer to ‘global value chains’ or GVCs with the recognition that international supply chains may often be regional, rather than global (WTO, 2013).

The fragmentation of production processes associated with the rise of GVCs allows firms in small economies and developing countries to participate in international trade without developing the full range of vertical capabilities across a value chain. By opening up access to new and often higher value markets, participation in GVCs can offer smaller and emerging economies an opportunity to add more value within their local industries, expand employment and raise incomes. But this also requires efforts at the national level to mainstream GVC trade into economic development, build greater internal capacity and generate more linkages with the local economy (Bamber et al., 2014a, 2014b).

Many developing countries and small economies alike are trying to support domestic firms to link to GVCs. They are also trying to attract foreign firms and improve border procedures to facilitate trade flows. While some studies urge governments to further reform their trade policies and streamline border clearance measures, they also emphasize that inducing the long-term participation of firms in these competitive value chains can be very challenging. This is true especially since GVCs in today’s world are highly dynamic. They place strict demands on participating firms and are increasingly consolidated around a small number of strong global lead firms.

An OECD study, ‘Connecting local producers in developing countries to regional and global value chains,’ finds that regardless of a firm’s position in the value chain, minimum quality, cost, and reliability requirements must be consistently met in order to participate in the chain on an ongoing basis (Bamber et al., 2014a). It finds also that the capacity of firms to consistently meet some of these requirements is affected by the local institutional context in which they operate. These local-level aspects of value chains include ‘the skill level of the available human capital, the establishment of local standards systems, specific infrastructure policies and the degree of industry institutionalization’. Joining a GVC, however, does not always translate into positive development gains from trade. Concerns exist that GVCs can increase inequality or have other adverse effects. Therefore, polices to integrate into GVCs should include economic, social and environmental dimensions which could help reduce such potentially negative impacts of GVC participation (Kaplinsky, 2005).

What are the opportunities that GVCs can offer small economies?

Integration into GVCs can help small economies diversify their production and export structure away from natural resources or primary agricultural commodities to manufacturing and services, where labour productivity and wages are higher (WTO, 2014). Typical sectors for an initial integration are apparel and clothing in manufacturing and call centres and IT business process outsourcing in services. Structural change can also be facilitated by the fact that certain tasks or skillsets can be exploited by different GVCs.

A main benefit from integration into GVCs is employment creation. The creation of new jobs does not only result in static gains by reducing underemployment but also allows for dynamic gains such as improved skills and employability of the labour force. However, successful integration into GVCs makes small economies vulnerable to negative shocks, at least in the short term, from potential GVC disintegration due to the decreasing competitiveness of domestic firms or due to the re-location of production by foreign investors.

Small economies, which do not have the endowments to create economies of scale in a broad range of activities, can benefit from GVCs by specializing in specific tasks or products. Integration might be easier in services than manufacturing. In particular, transportation costs of manufacturing products tend to be high for small economies as several of them are islands and remote from potential trading partners. Besides economic development, GVCs can spread international best practices in social and environmental efforts through the use of standards linked to corporate social responsibility (UNCTAD, 2014).

What are the challenges for small economies to integrate into GVCs?

GVCs pose two interlinked challenges. First, small economies need to establish policies and a business environment that allows domestic firms to improve their productivity to the point that they are able to integrate into GVCs, either through exports or by supplying foreign affiliates located in their market. Second, is the challenge of attracting FDI. According to UNCTAD (2013), determinants for investment and GVC activities can be broadly grouped into horizontal determinants that are the same across sectors or production stages, and determinants that tend to be sector or stage-specific.

Horizontal determinants relate to political and economic stability, the business environment, market size, infrastructure and the policy framework. These determinants often ‘make or break’ investment decisions. Results from Aid-for-Trade questionnaires of firms operating in five different value chains show that they share a number of major obstacles when trying to connect to value chains. In particular, suppliers from small economies and other developing countries and lead firms highlight transportation costs and related infrastructure, access to (trade) finance, customs procedures, labour skills, inadequate standards infrastructure and the regulatory and business environment as major obstacles to the participation of developing country suppliers in GVCs (OECD/WTO, 2013).

Beyond these necessary horizontal conditions for GVC integration, different stages and sectors are characterized by specific requirements to be met by potential suppliers and their host countries. In the case of knowledge creation stages such as research and development (R&D) and design, sp...