![]()

1

Introduction

Discovering the nature of relationships between variables is a very important part of any scientific field. In the well-established sciences, the variables to be related are precisely defined and widely accepted by the scientific community as the important variables to study. The relationships of these variables with each other are frequently specified mathematically, and these mathematical relationships between variables in some cases are further organized into elaborate mathematical theories involving several interrelated variables. In the newer scientific fields the variables are less precisely defined, there is not so much agreement among scientists concerning what variables should be related to each other, and the nature of the relationships between variables is less clearly specified. Factor analysis represents a rapidly growing body of statistical methods that can be of great value in these less developed sciences. Factor analytic methods can help scientists to define their variables more precisely and decide what variables they should study and relate to each other in the attempt to develop their science to a higher level. Factor analytic methods can also help these scientists to gain a better understanding of the complex and poorly defined interrelationships among large numbers of imprecisely measured variables. The purpose of this book is to help the reader achieve some familiarity with these powerful methods of analysis.

This book has been written for advanced undergraduate students, graduate students, and research workers who need to develop a knowledge of factor analysis, either for the purpose of understanding the published research of others or to aid them in their own research. It is presumed that most readers will have a reasonable understanding of high school geometry, algebra, trigonometry, and a course in elementary statistics, even though the concepts in these areas may not have been reviewed recently. Some sections of the book make use of more advanced mathematical techniques than the typical high school graduate is exposed to, but this should not prove to be an obstacle of any significant proportions for the average reader. The authors have tried hard to present the material in a way that can be understood by interested students with only a modest mathematical background. Although the book has been designed to serve as a textbook for classes in factor analysis, it was also written with the expectation that many of the readers will be using it without the guidance of a teacher.

Factor analysis represents a class of procedures for treating data that are being applied with increasing frequency in the behavioral and health sciences and even in the physical sciences. Despite this popularity, however, factor analysis is not well understood by many of the scientists who use it. There are many reasons for this phenomenon. First of all, factor analysis is based on mathematical foundations that go beyond the level of quantitative sophistication and training possessed by the bulk of behavioral scientists who use it the most. Although there are several excellent books (e.g., Harman, 1967; Horst, 1965; Mulaik, 1972) that present the mathematical background of factor analysis, the average behavioral scientist is unable or unwilling to wade through these books, largely because of his or her limited mathematical skills.

Another problem with understanding factor analysis, however, is that it rests on empirical science as much as it does on mathematics. The person who is well trained in mathematics will have little difficulty with the mathematical aspects of the topic, but without training in empirical science applications of factor analysis, can be expected to have difficulty making effective use of these methods in practice. It is also true that the textbooks that are comprehensive with respect to the mathematical aspects of factor analysis do not deal with the nonmathematical parts of the subject with the same degree of adequacy.

Thus, neither mathematical skill nor scientific sophistication alone is sufficient to understand and use factor analysis effectively. Knowledge in both these areas is needed. An attempt is made in this book to present in both these realms the ideas that are necessary for a basic understanding of factor analysis and how to use it. No attempt has been made to provide an exhaustive coverage of all the methods used in factor analysis. Rather, the focus in this book is on the correct use and understanding of some practical, proven procedures. Step-by-step instructions are given that will permit the reader to apply these techniques correctly. In addition, an attempt has been made to explain the underlying rationale for these methods. Without a fundamental understanding of why certain procedures are supposed to work, application of factor analysis becomes a cookbook operation in which the user is not in a position to evaluate whether or not what is being done makes any sense. The first goal of this volume, therefore, is to promote understanding as a basis for proper application. Understanding is also the basis for intelligent evaluation of published applications of factor analysis by others. Most scientists need this capacity today whether or not they ever do a factor analysis.

This book provides more emphasis on the nonmathematical aspects of factor analysis than the books mentioned above. Although this book presents the essential aspects of the mathematical basis of factor analysis, it does so on a simpler level than that found in these more mathematical texts. It is hoped that the mastery of the content of this book will provide a ready avenue for progression to more advanced mathematical treatments of the subject. The nonmathematical aspects of the present treatment will also provide a useful background for placing more advanced mathematical material in proper perspective as well as making it easier to absorb. Some textbooks on factor analysis that may offer valuable assistance to the reader who wishes to explore the topic further include the following:

Cattell (1952), Factor Analysis. This is a book of intermediate difficulty in which simple structure is emphasized as a means of carrying out factor rotations. Ways of combining factor analysis with experimental design are described.

Cattell (1978), The Scientific Use of Factor Analysis. Cattell summarizes his major developments in the area of factor analysis since his 1952 book. Other important developments in factor analysis by other researchers besides Cattell and his students are also presented. The mathematics required to read this book are not extensive. Cattell addresses many issues that are still current in using factor analysis.

Fruchter (1954), Introduction to Factor Analysis. An elementary book that provides an easy introduction.

Gorsuch (1983), Factor Analysis. An intermediate level of difficulty and a balance between theory and applications.

Guertin and Bailey (1970), Introduction to Modern Factor Analysis. This book avoids mathematics and concentrates on how to use the computer to do factor analysis. It is easy to read but does not emphasize an understanding of the underlying theory.

Harman (1967, 1976), Modern Factor Analysis. A comprehensive treatment with a mathematical emphasis. Difficult to read.

Horst (1965), Factor Analysis of Data Matrices. Entirely algebraic treatment. Difficult for the non-mathematical reader.

Lawley and Maxwell (1963), Factor Analysis as a Statistical Method. This is a little book that presents, among others, Lawley’s own maximum likelihood method. Some mathematical sophistication is required to read this book.

Mulaik (1972), The Foundations of Factor Analysis. A comprehensive treatment of the mathematical basis for factor analytic methods. Difficult for the nonmathematical reader.

Rummel, R. J. (1970), Applied Factor Analysis. A book of intermediate difficulty. Contains good chapters on matrix algebra and its use in factor analysis. Presents many of the traditional approaches but does not discuss extensively the issues involved in the use of different exploratory factor models. The author presents several examples using political science variables instead of psychological variables. The different factor models are well explained.

Thomson (1951), The Factorial Analysis of Human Ability. Presents the point of view of an important British historical figure in factor analysis. Easy to read.

Thurstone (1947), Multiple Factor Analysis. This is the classic historical work by the father of modern factor analysis. It still contains much of value to the advanced student.

The authors recommend that after mastering the material in the present text, the reader should go on to read other texts from the list above. Journal articles on factor analytic methods are to be found in such periodicals as Psychometrika, Multivariate Behavioral Research, Educational and Psychological Measurement, and Applied Psychological Measurement. Many other journals report research in which factor analysis has been used to treat data.

1.1. FACTOR ANALYTIC GOALS AND PROCEDURES

There are many reasons why an investigator may undertake a factor analysis. Some of these are the following: (a) He or she may have measurements on a collection of variables and would like to have some idea about what constructs might be used to explain the intercorrelations among these variables; (b) there may be a need to test some theory about the number and nature of the factor constructs needed to account for the intercorrelations among the variables being studied; (c) there may be a desire to determine the effect on the factor constructs brought about by changes in the variables measured and in the conditions under which the measurements were taken; (d) there may be a desire to verify previous findings, either those of the investigator or those of others, using a new sample from the same population or a sample from a different population; (e) there may be a need to test the effect upon obtained results produced by a variation in the factor analytic procedures used.

Whatever the goals of an analysis, in most cases it will involve all of the following major steps: (a) selecting the variables; (b) computing the matrix of correlations among the variables; (c) extracting the unrotated factors; (d) rotating the factors; and (e) interpreting the rotated factor matrix. The variables studied in a factor analysis may represent merely a selection based on what happens to be available to the investigator in the way of existing data. On the other hand, the variables chosen may represent the results of a great deal of very careful planning.

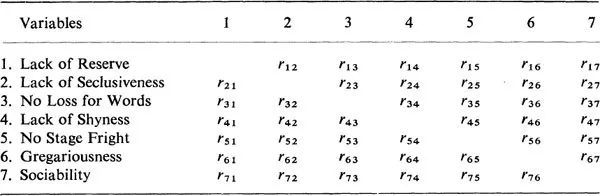

The factor analysis proper typically begins with a matrix of correlation coefficients between data variables that are being studied. In psychology, for example, these variables might consist of test scores on several short tests of personality, such as 1. Lack of Reserve, 2. Lack of Seclusiveness, 3. No Loss for Words, 4. Lack of Shyness, 5. Lack of Stage Fright, 6. Gregariousness, and 7. Sociability. These tests might be administered to several hundred students. A correlation coefficient would be computed between each pair of tests over the scores for all students tested. These correlation coefficients would then be arranged in a matrix as shown in Table 1.1. Numerical values would appear in an actual table rather than the symbols shown in Table 1.1. Thus, the correlation between variables 1 and 2 appears in the first row, second column of the correlation matrix, shown in Table 1.1 as r12. The subscripts indicate the variable numbers involved in the correlation. It should be noted that the entry r21 (in row 2, column 1) involves the correlation between variables 2 and 1. This is the same as r12 since the same two variables are involved. The correlation matrix, therefore, is said to be “symmetric” since rij = rji, that is, the entries in the upper right-hand part of the matrix are identical to the corresponding entries in the lower left-hand part of the matrix.

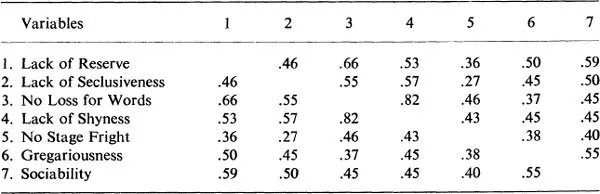

The symbols shown in Table 1.1 are replaced by hypothetical numerical values to give the correlation matrix shown in Table 1.2. The matrix shown in Table 1.2 is a very small one, of course, being only a 7 × 7 matrix involving just seven variables. Matrices treated in actual research work frequently run to 60 × 60 or more, that is, involving 60 variables or more. The symmetric character of the matrix in Table 1.2 is seen by observing that the numbers above the main diagonal (the imaginary line through the blank cells in Table 1.2) are the same as those below the main diagonal. Also, the entries in row 1 are the same as those in column 1. The same thing holds for all other rows and columns that have the same number if the matrix is symmetric.

When the correlation matrix has large correlation coefficients in it, this indicates that the variables involved are related to each other, or overlap in what they measure, just as weight, for example, is related to height. On the average, tall people are heavier and short people are lighter, giving a correlation between height and weight in the neighborhood of .60. With a large number of variables and many substantial correlations among the variables, it becomes very difficult to keep in mind or even contemplate all the intricacies of the various interrelationships. Factor analysis provides a way of thinking about these interrelationships by positing the existence of underlying “factors” or “factor constructs” that account for the values appearing in the matrix of intercorrelations among these variables. For example, a “factor” of “Bigness” could be used to account for the correlation between height and weight. People could be located somewhere along a continuum of Bigness between very large and very small. Both height and weight would be substantially correlated with the factor of Bigness. The correlation between height and weight would be accounted for by the fact that they both share a relationship to the hypothetical factor of Bigness.

TABLE 1.1

A Symbolic Correlation Matrix

TABLE 1.2

A Numerical Correlation Matrix

Whether or not it is more useful to use a single concept like Bigness or to use two concepts like height and weight is a question that cannot be answered by factor analysis itself. One common objective of factor analysis, however, is to provide a relatively small number of factor constructs that will serve as satisfactory substitutes for a much larger number of variables. These factor constructs themselves are variables that may prove to be more useful than the original variables from which they were derived.

A factor construct that has proved to be very useful in psychology is Extraversion-Introversion. It is possible to account for a substantial part of the intercorrelations among the variables in Table 1.2 by this single factor construct. This is because all of these variables are correlated positively with each other. With most large real data matrices, however, the interrelationships between variables are much more complicated, with many near-zero entries, so that it usually requires more than one factor construct to account for the intercorrelations that are found in the correlation, or R, matrix.

After the correlation matrix R has been computed, the next step in the factor analysis is to determine how many factor constructs are needed to account for the pattern of values found in R. This is done through a process called “factor extraction,” which constitutes the third major step in a factor analysis. This process involves a numerical procedure that uses the coefficients in the entire R matrix to produce a column of coefficients relating the variables included in the fac...