![]()

1 Win-win-win? Ecologically, socially

and economically sound services

During the recent decade, services have been acknowledged as one of the most prominent solutions to reduce the material and energy intensity of consumption, and thus put a halt to one of the main sources of environmental degradation. Despite the high hopes placed on eco-efficient services, they have mainly not made such a great success among consumers as their proponents expected. Why not? What could be done to make eco-efficient service-based consumption and lifestyles more attractive among consumers?

This book is about services that are offered to consumers at their homes and affect sustainable development positively in its ecological, social and economic dimensions. It seeks to unravel some of the blind spots of sustainable consumer services, and thereby build the ground for more successful future service solutions. We ask what kinds of consumer services are sustainable, are there markets for those services and how to provide them in an economically feasible way.

Consumption patterns in the Western countries and among affluent consumers elsewhere in the world have been pointed out as one of the ultimate sources of environmental degradation. Much of this unsustainable consumption occurs in the context of households, that is to say living at home and moving to and from it. A number of solutions, including service-based lifestyles, have been proposed to change the present consumption philosophies. The ways in which services are expected to make society more sustainable vary among the proponents of service thinking. Some of them see the ‘service solution’ from the information society perspective: as the structures of industrial production turn from manufacturing-dominated to information-intensive service models, de-linking of economic growth and environmental burden occurs (Bell, 1976; Janicke et al, 1989). Some others take a ‘less automatic’ standpoint on the role of services. They do not foresee that an increasing share of services as a means of livelihood automatically reduces the environmental load. Instead they expect that in order to achieve eco-efficiency gains, service considerations must be crafted into models of production and consumption with the purposeful goal of reducing environmental impact of economic systems (Lovins, Lovins and Hawken, 1999). Within both streams of thinking, however, the sustainability of services has mainly been discussed from an eco-efficiency perspective rather than from a more holistic sustainability point of view. In other words, in the sustainable service literature, the social aspect of sustainability tends to be neglected at the cost of environmental and economic argumentation, which may be one of the reasons for the moderate success of eco-efficient services in the consumer market.

Moreover, citizen-consumers are often assumed to decide which products or services are being used. To some extent this is certainly true. However, depending on the consumption cluster (for example nutrition, mobility, or housing), households alone have only limited – greater or lesser, but still limited – possibilities to influence their patterns of consumption (Sanne, 2002; Roy, 2000). There are always other actors who are relevant in setting the frame for consumption choices. For instance with regard to housing and construction, property owners (housing providers), local authorities and service providers influence the housing framework. Or as regards mobility, local authorities and service providers have a lot to do with the transport infrastructure, and therefore they set the limits within which households are able to decide how to fulfil their mobility needs (Spangenberg and Lorek, 2002). This is another reason why it makes sense to seek for solutions for household sustainability with the service perspective in mind. Not only does this perspective capture the aspiration to shift consumption from products toward services, but it also takes into account other actors’ possibilities to influence the households’ consumption decisions.

To put it briefly, there are two major gaps in the sustainable service discussion: the lack of a holistic view of sustainability, and a disregard for the limited opportunity of households to influence their consumption choices. In order to include these issues, this book will put forth the idea of sustainable homeservices, propose some institutional arrangements with which to make them easily available for users, and explore the main drivers and hindrances for service-based household consumption.

The guiding questions of this book are:

• What are holistically sustainable household services and how to measure their sustainability?

• How to make consumers interested in using services that enhance sustainability?

• What kinds of delivery arrangements could enable the provision of such services?

• What kinds of business models suit the provision of sustainable household services and how to develop sustainable services?

This chapter starts with a brief discussion about services in general, and examines different types of eco-efficient services, as well as the ways in which they can reduce the use of material and energy resources. Following from the above-argued need to extend the eco-service discussion to explicitly include social or economic aspects, we will thereafter introduce the idea of a sustainable service – a concept that explicitly captures all sustainability dimensions. As we are interested particularly in consumer services that enhance sustainability, and argue that a considerable part of consumption relates to living at home, we introduce the concept, ‘sustainable homeservices’. The underlying effort in this chapter is a progressively refined articulation of that concept. However, we start by first justifying why it makes sense to speak about sustainability, services, and homes in the same connection.

PRODUCTS, SERVICES OR SOMETHING IN BETWEEN?

How do services differ from products? Traditionally it is considered that services differ from products in four main respects. First, they are intangible, and secondly, in many service operations, production and consumption cannot be separated. Customers are involved and participate in the production process (for instance personal energy counselling to a household). To name a third difference, services are experienced differently by different customers (for instance, customers who cannot distinguish between physical goods, such as TV sets off the same production line, will normally be able to distinguish between services, for instance the different maintenance persons of the maintenance firm). Finally, services are perishable, in other words they cannot be stored (Baron and Harris, 2003; Zeithaml and Bitner, 1996; Payne 1993).

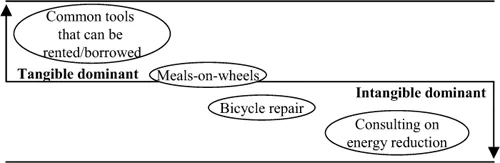

However, the difference between products and services becomes less pointed if we look at product and service offerings more closely. All products include some service, such as delivery, and all services require the use of some tangible elements, products (for instance premises) (Heiskanen and Jalas, 2003). This can be illustrated with Shostack's (1977) classical tangibility continuum (Figure 1). It is presented beneath with some examples adapted to the household service context. The model classifies products and services based on the amount of tangible and intangible elements (Baron and Harris 2003, Payne 1993).

Figure 1. Tangibility continuum adapted to the household services

The definition of services suggested by Heiskanen and Jalas (2003) is the most suitable one for the present purpose, because it avoids the pitfall of service versus product definition. According to them, service is an added value for the customer, that is, an economic activity which replaces the customer's own labour with activities conducted by the service provider, either personally, automatically or in advance through planning and design.

SUSTAINABLE SERVICES ARE MORE THAN ECO-EFFICIENT

The discussion about ‘sustainable services’ or ‘sustainable product-service systems’ has tended to emphasise the eco-efficiency perspective rather than explicitly capture all sustainability aspects (Tukker, 2004; Roy, 2000). Particularly social or socio-economic considerations have received very little attention. This may be one of the underlying reasons why eco-efficient service concepts, especially those directed to consumers have not been as successful in the market as their proponents hoped. We argue that sustainability must be seen in a more comprehensive fashion in the service discussion and research, as a concept that includes ecological, social and economic aspect with an equal weight. The added value of eco-efficient services to consumers may actually often relate to considerations lying in the sphere of social sustainability (Hobson, 2002; McMakin, Malone and Lundgren, 2002).

However, in this section we will first discuss the ways that various services can contribute to eco-efficiency. As there is fairly abundant research on eco-efficient services, the following discussion outlines the main streams of research on the eco-efficiency of services and presents a typology of eco-efficient services. Thereafter we address the need to comprehend sustainable services as a more extensive concept than merely eco-efficient services and put forward the idea of adding the social dimension to sustainable service thinking.

Brief introduction to eco-efficient services

The notion of immateriality and intangibility often connected to services does not automatically lead us toward a more ecologically sustainable society (cf. Mont 2002; Heiskanen et al, 2001). There are, however, two main routes through which services can lead to a decreased environmental burden in society. The first one is the potential related to the general shift to services with a lower than average material intensity, such as medical or personal care, legal services, banking, and the like. From a macroeconomic perspective, the shift to services and thus the increased service intensity of the economy contributes to ecology through the decline of traditional smokestack and extractive industries in relation to less materials-intensive and more knowledge- and labour-intensive service industries. These services, however, are not necessarily eco-efficient. Their eco-efficiency must be assessed for each individual service and its context (cf. Salzman, 2000; Heiskanen et al, 2001).

As contended earlier, another route for approaching the ecological sustainability potential of services is the idea of eco-efficient services. According to that stream of research there are so-called eco-efficiency instances in which particular services or product-service combinations have the potential to reduce resource consumption while still fulfilling the same need of the consumer as the traditional alternative of owning the product. The ideas for eco-efficient service thinking come from many sources. One of its roots is in the so-called factor discussion that urges radical reductions in the intake of materials into the economy: by a factor of four (von Weizsäcker, Lovins and Lovins 1997) or by a factor of ten (Schmidt-Bleek 1998). This dematerialization and reduction in energy usage is expected to be achieved by fulfilling the needs of customers with the help of services instead of products, such as a car-sharing service instead of a private car. Services that replace products to a greater or lesser degree, and thus reduce the material and energy needed to perform an economic activity, for instance moving and cooking, are often called eco-efficient services. The above, however, is not to argue that all services replacing products are always necessarily more environmentally sound than a product fulfilling the same need. There are limitations to the eco-efficiency concept, such as the rebound effect (e.g. Jalas, 2002), but that as well as other critiques (e.g, Hukkinen, 2003) fall beyond the scope of this study.

It is possible to identify different types of eco-efficient services. They extend from conventional forms of renting, leasing and sharing to selling ‘solutions’ (e.g. integrated pest management) (Hockerts, 1999). A number of typologies have been developed in order to classify the broad range of services that can be seen to involve an eco-efficiency component. The classifications vary slightly depending on the author's line of reasoning. To draw an integrative classification based on the writings of Hockerts (1999), Heiskanen (2001), and Roy (2000), product-based services are services that are related to the use of a product. The product may be sold to the customer or not. In the former alternative the service component relates to repair, maintenance, upgrading or take-back of the product. The model can be seen as an example of extended responsibility of the producer even after the point of sale. The concept is relatively close to conventional manufacturing business – for instance the common practice of giving a guarantee extends the responsibility of the seller or producer of the product. Renting or leasing a product to the user goes a step further: the ownership remains with the producer. These kinds of services are sometimes also called use-oriented services, because only the use of product is being sold (e.g. in a car sharing concept, the use of the car is the offering). Use-oriented services can be divided into individual use and joint use. Leasing, renting and hire purchase are forms of individual use, whereas sharing and pooling are forms of joint use. These services produce potential environmental benefits because they lead to a more intensive use of fewer products by several consumers (Behrendt et al, 2003).

Result-oriented services are services within which the focus is on fulfilling customers’ needs, and which are or seek to be independent of a specific product (therefore sometimes called need-oriented services). This type of services can be seen as including various forms of contracting, for instance least-cost planning in the energy sector, facility management, or waste minimization services. Result-oriented service may be offered by the manufacturer, such as an energy provider. It may be profitable for the provider to promote energy-saving equipment. A decrease in demand through gains in efficiency allows the energy company to increase its market share without having to build new power plants. However, these kinds of services are frequently provided by another company, for instance an energy service company (Hockerts, 1999; Heiskanen et al, 2001; Roy, 2000). Especially within the consumer market, they may be provided by another organization such as a public or non-profit organization, as will be exemplified later in this book. In the case of result-oriented services, the responsibility for supplying the goods required for the service lies with the service supplier. Initially, a craftsman's service such as the installation of a heating system can be classified as a result-oriented service. In the traffic sector, cab services, public transport and air traffic are included in the term. Transport services are generally defined by external factors and managed by professionals (such as taxi driver, pilot). Other examples include energy services, which aim to reduce energy consumption. Instead of selling units of electricity, what is sold are heat, light and cold. This way, the supplier is no longer tied to the production of one product. The producer's main task is to put the best system components together to satisfy customer's specifications and ecological aspects and to find the best overall system solution. Contracting, although not very common in households, can be considered a typical result-oriented service: the contractor is committed to the energy management of a property and the contract holder pays for these services (Behrendt et al, 2003).

Why would the services outlined above contribute to eco-efficiency – to be precise, to a reduction in materials and energy consumption? There are a number of reasons why efficiency benefits may accrue. Firstly, if the ownership of the product remains with the manufacturer, there is an incentive to produce more durable goods. This is because income is created by selling the use of the product, not the one-time sale of the product itself. Secondly, a smaller stock of products is needed if consumers use the same product in sequence. The smaller the stock of products, the less material is needed to produce them. In other words, more intensive use increases the probability of higher service yield before the product becomes obsolete due to outdated technological characteristics or fashion, for instance. Often, for example cars or personal computers are exchanged for newer ones not due to their breaking apart, but for reasons that lie somewhere in the midway between outdated technology and fashion. Thirdly, in result-based services in which the operator takes responsibility for product use, the service may facilitate more professional product use. To mention one more instance of the potential of services, the service model may contribute to the choice of a product that is more relevant to the task. For example, in a car-sharing system, th...