- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rethinking Third-World Politics

About this book

Providing a thorough reassessment of our understanding of politics in Third World societies, this book contains some of the liveliest and most original analyses to have been published in recent years. The severity of the political and economic crisis throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America in the 1980s has highlighted the inadequacy of existing political science theories and the urgent need to provide new paradigms for the 1990s.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rethinking Third-World Politics by James Manor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Conceptualising Third World Politics

Chapter One

The Three-Dimensional State

After nearly three decades of searching for general theories of political development, most Western and Western-influenced scholars still have not abandoned their preoccupation with studying the causal relationships between democracy and socio-economic development, thus maintaining the fundamental assumption that political development is essentially a two-dimensional phenomenon. This is evident, for example, in a recent major work on democracy in developing countries, where one of the editors, a prominent political scientist, wrote in his introduction to the volume:

Generations of theory have grappled with the relationships between democracy and both the level and the process of socio-economic development. The evidence from our ten cases cannot settle the spirited theoretical controversies that remain with us. Nevertheless, some important insights do emerge. The most obvious of these is the simple static observation that democracy is not incompatible with a low level of development.1

This preoccupation reflects a certain poverty of ideas in Western political science. This in turn is rooted in its epistemology, which is essentially based on Aristotelian concept of politics, and rendered more permanent by the influence of the positivist behavioural scientists of the 1960s, who incorporated structural-functionalism into the study of comparative politics.

‘The polis is by physis’, wrote Aristotle in his Politics. The concept of physis implies the whole process of growth and the concept of being ‘grown’ as well as the beginning of growing. The whole organised political community (both the centre and periphery) is capable of growing, and can also be decaying, declining, degenerating.

The Aristotelian concept of ‘Dynamic Nature’ leads to the attempt to classify and typologise societies and political systems. Hence political development and modernisation theories, as Lucian Pye correctly observes, have generally been heuristic theories; the focus has been to spell out concepts and identify factors and processes so as better to guide empirical work. By providing preliminary bases for classification and typology-building, the theories set the stage for case-studies with comparative dimensions.2

This in turn has three major consequences. One is the tendency to conceive political development in terms of two general dichotomies, that is ‘modern’ versus ‘traditional’ societies, and ‘democratic’ versus ‘non-democratic’ political systems. The second is the predisposition to analyse political development in terms of qualitative changes in values, structures and functions of given political systems, where new values, structures and functions are seen to replace existing ones. The third is the notion that the process of qualitative change is characterised by conflict, whereby opposing forces, for example tradition and modernity, interact in a dialectical mode of thesis, anti-thesis and synthesis.

The modernisationist theorists, both the structural-functional and political cultural schools, have been similarly caught up in this ‘Aristotelian trap’. Political culture theorists have been criticised as being culturally deterministic as well as psychologically reductionist. It has also been pointed out that their theory suffers from a lack of dynamism since studies of political culture have failed to deal with the dialectical forces of change. More importantly, their concept of change is inextricably linked with incrementalism and gradualism which carries the political system to its natural end, to the ideal civic culture.3

Studies of political culture in the past three decades have relied heavily on analyses of the political socialisation process. The problem is that the mainstream of research focuses almost exclusively on the development of children’s political attitudes in stable democratic societies while adult experiences are treated as only marginally significant.

In his recent paper Gabriel Almond argued that the cultural determinism approach is a distortion of his and other theories of political culture and democracy. Political culture has never been viewed by this school as a uniform, monolithic and unchanging phenomenon, but rather as a ‘plastic’ phenomenon that is open to evolution and change over time. ‘Political culture affects political and government structure and performance – constrains it, but surely does not determine it’.4 This observation is confirmed by the empirical evidence from a recent comparative study of democracy in twenty-six developing countries. This study demonstrates that the political culture of a country, while it may affect the character and viability of democracy, is itself shaped by the contemporary political, economic and social structures, as well as by the historical and cultural inheritance of the past. In other words, the political culture may be as much a consequence of the political system as a cause of it.5

Perhaps the criticism of cultural determinism stemmed not from the charge that the political culture theory lacks dynamism but rather from its preoccupation with only one direction of change, that is along more democratic lines. While it is widely accepted that democracy is the least evil form of government, and democratic institutions are better than others that might be established, one may fail to understand the nature and dynamics of change in developing nations if ‘core component’ of democratic culture is rigidly used as a single frame of reference.

The main problem of political development theories is the tendency to conceive political development in terms of two general dichotomies; ‘modern’ versus ‘traditional’ societies, and ‘democratic’ versus ‘non-democratic’ political systems. There is also the predisposition to analyse political development in terms of qualitative change in values, structures and functions of given political systems, where new values, structures and functions are seen to replace existing ones. Any study of state elites and mass political culture in non-developing nations must first confront this epistemological issue.

In a recent study of the experience of nine states in Asia and the Pacific (China, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand), it was recognised that neither the classical Marxist approach nor the liberal structural-functional theory which lay behind much of the modernisationist approach was adequate in understanding the dynamism of changes in that region. The study views the state as relatively autonomous, and focuses its attention on the relationships between the state and society in the allocation and exercise of power. Although this study veered away from conventional approaches, it still suffers from the traditional tendency to make a typology of regimes based on Aristotelian concepts modified by Dahl. Hence the nine states in Asia and the Pacific are categorised into

- Leninist states representing essentially a monopoly of power by the state or party as master of the state

- democratic states representing a regime in which the officers of the state are selected by society by contestation in a free environment

- the authoritarian, semi-authoritarian and semi-democratic states representing varying degrees in between of the state’s influence over society or society’s influence over the state.6

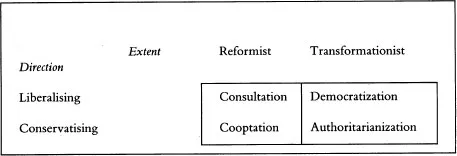

This study has also tried to establish a paradigm of political trends based on the above-mentioned model illustrated below in Figure l.7

Figure 1 Paradigm of Political Trends

Although this typology has incorporated a paradigm of political trends to reduce the mechanical nature of the model, it nevertheless neglects the arena or policy areas in which the state and society interact. The extent to which each regime performs its tasks may be a combination of both reformist and transformationist means, and it is debatable whether a liberalising direction is pursued in all policy areas. In other words, while China, the Soviet Union, Vietnam, Kampuchea, and Laos have shown some liberalising trends in economic activities (the development dimension), party leaders in these countries are less keen to pursue the same approach in other policy areas (security and political participation).

The paradigm rooted in Aristotelian epistemology is inappropriate for studying Asian political systems. For in these systems the relationship between state and society is more complex and multidimensional than in Western ones. And liberal democratic values, structures and functions – if they exist at all – constitute only one dimension of state-society relations. Furthermore, in Asian societies, change largely involves adjustment and coexistence between opposing forces, rather than conflict playing itself out through an objective dialectical process. Or to put it another way, in Asian societies, political cultures, structures, functions and processes are mixed.

The relationship between state and society in developing nations is a three-dimensional one, namely security (S), development (D) and participation (P), and the resultant political processes involve interactions among these three dimensions. Here ‘democracy’ is not a form of political system or a type of regime à la Aristotle, but a dimension of state—society relations which, are in flux, adjusting to or coexisting and interacting with other dimensions of the state-society relationship.

The dominance of one dimension over the others is due to four major variables related to the state: ideological domination, institutionalisation of structure, the capacity to control and utilise resources, and the adaptive capacity (or the capacity to escape the surrounding societal forces).

Hence, instead of using the Aristotelian concept of political change and development which views changes in terms of societal forces opposing and replacing one another in a progressive unilinear direction, the three-dimensional state model argues that Third World states encompass within themselves many apparently contradictory characteristics and structures, for example those of development and underdevelopment, democracy and authoritarianism civilian and military rule, at the same time. These contradictory characteristics of Third World political systems are a reflection of their economic and social structures and the different modes of production – feudal capitalist and even socialist – that coexist within Third World societies. At the political level such structures and characteristics struggle against each other, but most of the time, they also come to terms with each other and continue to coexist in uneasy harmony.

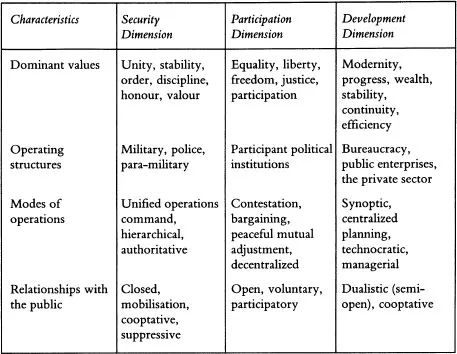

Figure 2 (p. 20) shows major characteristics of the Three-Dimensional State coexisting, interacting without any single dimension or mode being capable of completely replacing the other. The result is not a synthesis which exists in one form (democracy, authoritarianism), but an evolving admixture with three dimensions coexisting.

Because there is no single enduring synthesis, it is impossible to speak of a political system and politics as an authoritative allocation of values in society. It is also difficult to apply concepts of legitimacy and consensus in such a complex situation, as in the cases of Burma and Kampuchea, since there are not only competing ‘primordial’ loyalties (ethnic, cultural) but also, highly complicated ideological values, operating structures, modes of operations and relationships which each group has with the public. The unsettled conflict in Kampuchea is a classic example of a situation in which the Eastonian concept of politics became analytically ‘dysfunctional’.

The Three-Dimensional State model recognises a long-standing fact: that a regime, no matter what type of power distribution it has, must pursue at least three goals in order to maintain its power.

Figure 2 The Three-Dimensional State: Major Characteristics

It is this relatively all-encompassing legitimacy formula that forces rulers of Third World states to express concern for two other dimensions of the political system – development and participation – that have gained increasing importance during the twentieth century in the world at large, and in the last four decades in the decolonised parts of the globe in particular. The rulers’ interest in these two dimensions of the political system is principally based on their recognition that they cannot achieve a degree of legitimacy in the eyes of their subjects (which would allow them to sustain themselves in power without excessive use of force) unless their preoccupation with security is tempered by their concern for the economic development of the people over whom they rule or, alternatively, their commitment to enlarge their popular base of support by providing increasing avenues for the participation of the citizenry in the political life of the country and in the choice of its rulers. Better still, if they are able simultaneously to appear committed to both developmental and participatory values, in addition to their commitment to the security of the state, their legitimacy among their countries’ populations is usually greatly enhanced.

This emphasis on development and participation in addition to security and state-building immensely complicates the task of Third World leaders for, as a result, the demands upon them have increased three-fold as compared to the demands on the rulers of the early period of the absolutist state in Europe (for that is the comparable stage of development in terms of state-building that most Third World states are at today). Those European rulers could single-mindedly pursue their goal of state-building without being bothered about escalating demands for political participation and economic redistribution. While the generation of national wealth was one of their major goals as well, this was pursued for the sake of augmenting the power of the absolutist state and, therefore, was an instrument of state-building and was accompanied by a strategy for the centralisation of control over economic resources. It was not perceived by the rulers of the absolutist state as a part of a welfare ideology that was essential to their legitimacy formula.

Today the demonstration effect produced by the existence of the representative and welfare state in most parts of the industrialised world on the populations of the Third World states makes it imperative that Third World leaders swear by the values of development and participation if they are to achieve the minimum legitimacy necessary for them to carry out the work of governing their societies without the use of excessive and brutal force. The different ways in which they do this provide the variations on what can be called the SDP state, where S stands for security, D for development and P for participation. Theoretically these variations can range from SDP, where security is the paramount value, followed by development and participation in that order, to PDS where participation is the paramount value, followed by development and security in that order. The possible variations lying in between are, once again theoretically, SPD, DSP, DPS and PSD.

However, most post-colonial and most South-east Asian regimes are likely to assign the highest value to security among the three objectives mentioned above. But in some cases and for limited periods participation – in the case of the Philippines just after the overthrow of Marcos – can temporarily reach the top of a particular government’s political agenda. Such an ordering of priorities usually does not last very long and the insecurities of post-colonial state structures as well as of their regimes soon reassert themselves to make security the prime consideration once again. This happened in the Philippines once the euphoria generated by the ‘People Power’ revolution had declined. This means that for all practical purposes, there are only two types of states and regimes that we need to be concerned with in our analysis: the SDP state, where development takes precedence over participation, and the SPD state, where participation takes precedence over development. In both cases security remains the foremost objective of the governments concerned.

Nevertheless, even when in normal times security is accorded pride of place in governmental agendas around the Third World, including in South-east Asia, there are two characteristics that distin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Part One: Conceptualising Third World Politics

- Part Two: The Theatrical and Imaginary Dimensions of Politics

- Part Three: Political Institutions and State-Society Relations

- Index