![]()

Chapter One

John Horne Tooke and Linguistic Equality

F.: Must we be always seeking after the meaning of words? H.: Of important words we must, if we wish to avoid important errors. The meaning of these words especially is of the greatest consequence to mankind; and seems to have been strangely neglected by those who have made the most use of them.

John Horne Tooke, Epea Pteroenta, or, The Diversions of Purley, Part II (1805), p. 4.

In the Dictionary of aristocratic Prejudice, Illumination and Sedition are classed as synonimes, and Ignorance prescribed as the only infallible Preventive for Contention. …The mind is predisposed by its situations: and when the prejudices of a man are strong, the most overpowering Evidence becomes weak. … Some unmeaning Term generally becomes the Watch-word, and acquires almost a mechanical power over his frame.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Conciones ad Populum, or, Addresses to the People (1795), in Lectures 1795 on Politics and Religion, p. 52.

Introduction

In late November 1795, writing in response to the Seditious Meetings and Treasonable Practices Bills, Samuel Taylor Coleridge condemned William Pitt’s ‘foul treason against the majesty of man’. Bishop Horsley’s assertion in the House of Lords on 11 November 1795 – that ‘the Mass of the People [had] nothing to do with the Laws, but to obey them’ – had outraged Coleridge with its injunction to a passive and silent obedience, now to be enforced through the new legislation limiting freedom of speech, publication and assembly. Pitt’s administration, it seemed, was intent on gagging all free enquiry, effectively turning the Treason Trials of 1794 into legal action against ‘the mass of the people’ by extending the prosecution which had failed against the alleged traitors, John Thelwall, Thomas Hardy and John Horne Tooke, in order to outlaw the voice of the nation.1 The authorities were attacking the free exchange of words and ideas, and Coleridge returns their fire by investigating the meaning of one of the words at the heart of the struggle between government and people. The two bills, which would later come to be known as the Gagging Acts, were expressly designed for the safety of His Majesty’s person after the furore over the mobbing of the King’s carriage on 29 October 1795, the day of the state opening of Parliament.2 But as Coleridge points out, the blurring of the line between words and actions implied by the outlawing of voices critical of establishment policies and institutions had far-reaching consequences, so that ‘if even in a friendly letter or in social conversation any should assert a Republic to be the most perfect form of government, … he is guilty of High Treason’. According to the interpretation of Pitt’s regime, ‘to recommend a Republic is to recommend an abolition of the kingly name’, constituting an implicit threat to the King’s person.3 Abolishing the name of king by substituting for the monarchical system a model of social and political organization which recognizes the need to make government more genuinely a ‘res publica’, a matter which concerns and involves the public at large, has falsely been equated with king-killing, alleges Coleridge. To counter this false association, he firstly suggests that the new law is itself a conspiracy to cause harm to the King, a ‘pernicious’ law, because it would ‘shut out his Majesty from the possibility of hearing truth’; in effect, committing treason against the intellect and morals of the King.4 But Coleridge also retaliates by questioning the true meaning of the word ‘majesty’, picking up the phrase that he uses at the beginning of his pamphlet, ‘foul treason against the majesty of man’. Tracing the word back to its ‘original signification’, Coleridge suggests that true sovereignty belongs to the ‘mass of the people’, since ‘majesty’, properly so called,

meant that weight which the will and opinions of the majority imparted. Majesty meant the unity of the people; the one point in which ten million rays concentered. The antient Lex Majestatis, or law of Treason was intended against those who injured the People; – and Tiberius was the first who transferred this law from the people to the protection of tyrants. – In our laws the King is regarded as the voice and will of the people: which while he remains, it is consequently treasonable to conspire against him.5

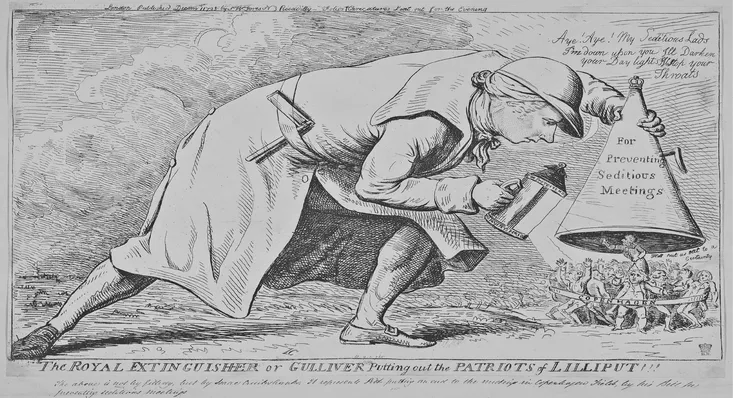

Coleridge is, in fact, ironically echoing the established legal thinker, Sir William Blackstone, here: in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, Blackstone refers to the King as a ‘centre’ in whom ‘all the rays of his people are united, and form by that union a consistency, splendour, and power’.6 But he only possesses this power and splendour while he remains the ‘voice and will of the people’, Coleridge implies: if he ceases to represent their wishes and interests, he loses the sovereignty conferred upon him. To drive his point home, Coleridge insists that Thelwall – one of the accused in the 1794 Treason Trials and a famous radical activist – is ‘the voice of tens of thousands’, and that by accusing Thelwall of sedition, Pitt is attacking the whole sovereign nation or state.7 Isaac Cruikshank’s satirical print, ‘The Royal Extinguisher’, published in December 1795, makes a similar play with the idea of rays of light: here, it is the seditious ‘illumination’ of radical discourse, personified by Thelwall in mid-oration

Fig. 1.1 Isaac Cruikshank, 'The Royal Extinguisher or Gulliver putting out the Patriots of Lilliput!!!'. 1 December 1795, BM8701

amid a crowd of reformers, that is ‘extinguished’, the targets of suppression pin-pointed by a single ray of light emanating from the dark-lantern of Pitt’s Gagging Acts.

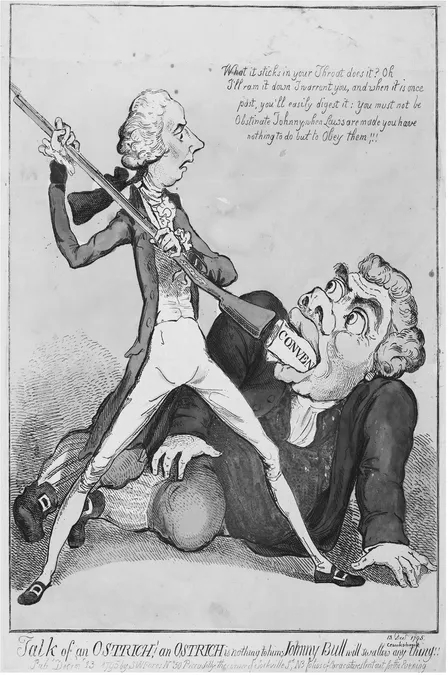

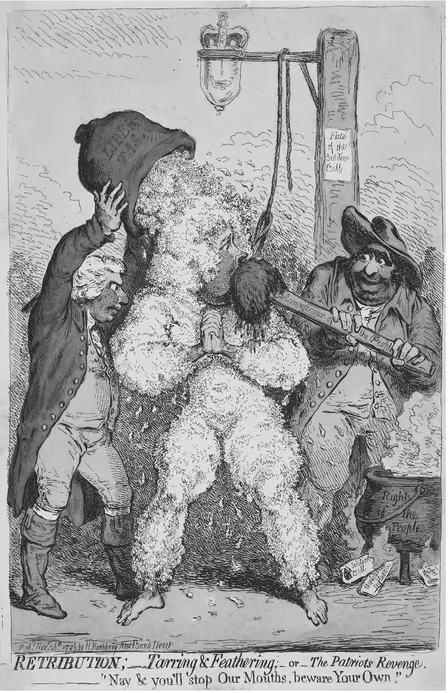

Coleridge’s definition of ‘majesty’ makes a nonsense of the two bills, revealing what Horne Tooke had, in 1786, called the ‘grimgibber’ of ministerial betrayals of language as well as of justice and law.8 If ‘majesty’ was properly to be interpreted as signifying the ‘majority’, the ‘mass of the people’, then to forbid freedom of speech and the press was itself a treasonable practice. The assault on civil liberties that both the new legislation and the government’s usurpation of the sovereignty of the majority were held to represent among reformers is graphically illustrated in another print of 13 December 1795, in which a tall, thin William Pitt stands over John Bull, ramming his ‘Convention’ Bill down John’s throat with the butt-end of a musket, and telling him: ‘What it sticks in your Throat does it? Oh I’ll ram it down I warrant you, and when it is once past, you’ll easily digest it: You must not be obstinate, Johnny; when Laws are made you have nothing to do but to Obey them!’9 Interestingly, although Pitt’s action and words suggest dominance, he is much smaller and slighter than the semi-recumbent, gigantic John Bull, and wears a look of alarm and anxiety on his face, perhaps suggesting his awareness of the illicit character of the ‘majesty’ that he and his government are claiming in their move to stop the mouths of the nation. Gillray’s ‘Retribution; – Tarring & Feathering; – or – the Patriot’s Revenge’ takes the hint, imagining the punishment that Pitt’s arbitrary law might draw down on his head, if the might of the people were to be exercised; Sheridan and Fox, leaders of the radical opposition, threaten: ‘Nay & you’ll stop our Mouths, beware your Own.’

Taken together, Coleridge’s politicized deconstruction of ‘majesty’ and West’s ‘Talk of an Ostrich’ clearly indicate how democratic politics and a politics of language could combine to resist the encroachments of government on the rights of the people. But the terms in which both printmaker and young poet chose to oppose government interpretations of English law and language suggest the importance of another John – John Locke – to reformers. More about the radical aspects of Locke’s theory of language will follow; for the moment, I want to show how Coleridge’s exposure of the corruption of the meaning of ‘majesty’ by government drew on Locke’s Two

Fig 1.2 Benjamin West, ‘Talk of an Ostrich! An Ostrich is Nothing to Him; Johnny Bull will Swallow Any Thing!’, 13 December 1795, BM8703

Fig 1.3 James Gillray, ‘Retribution; Tarring & Feathering; – or – ‘The Patriot’s Revenge’, 26 November 1795, BM8698

Treatises of Government – of which he had made an ‘intense study’ in 1794 – and how this links the young Coleridge to Horne Tooke.10

In his Second Treatise of Government, published in 1689, Locke had argued that while ‘born Free as we are born rational’, community, or civil society, was based on the power originally held by each individual being given over to ‘the majority of the Community’; this, he asserted, was the basis of ‘any lawful Government in the World.’11 The legitimacy of the ruler or government in Locke’s theory ‘has its Original only from Compact and Agreement, and the mutual Consent of those who make up the Community’. Tyranny could be defined as ‘the exercise of Power beyond Right.... When the Governour, however intituled, makes not the Law, but his Will, the Rule’. That phrase, ‘however intituled’, and the very specific construction being placed on ‘Law’ here, suggest Locke’s awareness of the importance of accurate word-choice, and again make it clear that for Locke, legitimacy is derived from mass consent (the force behind law-making) rather than from abstract, unfounded claims to absolute power. In such cases, Locke explains, ‘Law ends, [and] Tyranny begins, .... whosoever in Authority exceeds the Power given him by the Law, ... ceases in that to be a Magistrate, and acting without Authority, may be opposed, as any other Man, who by force invades the Right of another.’12 Although Locke is cautious about how far such opposition may extend, he...