![]()

PART ONE

TENDENCIES

TOWARD FRAGMENTATION

![]()

CHAPTER II

THE SIZE AND COMPLEXITY OF

THE FOREST SERVICE JOB

A Profile of the Forest Service

Even in agencies with simple, routine responsibilities, welding the behaviors of field personnel into integral patterns is often a trying experience. If, in addition, the field personnel operate under widely varied conditions, the difficulties of integration are multiplied many times. If, furthermore, the field units are too scattered to readily permit close supervision of their activities by agency leaders or co-ordination by personal contact among the men in the field, the difficulties increase exponentially. And if their responsibilities have not grown gradually, over many generations, enabling the members of the organization to work out their adjustments slowly, the administrative burden may be staggering.

All of these hardships beset the Forest Service. Its tasks are complex and require the exercise of broad discretion. No two of its field units face precisely the same problems, and conditions in some parts of the country barely resemble those in others. The tracts managed by the Service are scattered across the breadth of a continent and beyond. Its assignments have been thrust upon it in a relatively short space of time. Great indeed are the challenges to its administrative officers.

DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENT SCOPE OF RESPONSIBILITIES1

Not until 1876—a full century after the signing of the Declaration of Independence—was there even the germ of an administrative agency for forest management in the United States government, and even the germ planted in that year was not especially robust. A few statutes enacted prior to this had the effect of protecting timber on federal lands from depredations, and one encouraged the planting of trees on western prairies, but no administrative machinery was established. Indeed, forests were long regarded merely as impediments to the westward flow of population; clearing them away was more important than protecting them. Besides, the “legend of inexhaustibility,” according to which the forests were too extensive to be depleted by the feeble efforts of mankind, held sway. So it was a hundred years before a forestry organization was set up.

The beginnings were modest indeed—a special unit established by administrative action in the Department of Agriculture, with appropriations of just $2,000, to gather historical and statistical information about forests and forest products. In 1881, however, it was elevated to the status of an administrative division, and in 1886 received permanent statutory rank. Appropriations increased over the years, but they were still only $48,000 at the turn of the century. Under Bernhard E. Fernow, the Forestry Division built a name, expanded its research activities to include technical forestry subjects as well as history and statistics, and undertook a vigorous campaign of public education. Nevertheless, it still had no part in actual operations in the woods.

Fernow resigned in 1898 and was replaced by Gifford Pinchot. In three years, the division was reorganized and became the Bureau of Forestry, furnishing a vehicle for Pinchot to implement his philosophy of the role of government in relation to forestry, a philosophy that shaped and colored the relationship for years to come and also left a permanent impress on the organization. Research and information were all right as far as they went, but the real work of a public forestry agency, as he saw it, had to be centered on work that went on in the field. He therefore initiated a program of assistance to private owners of forest lands and started the training of personnel in practical forest administration; by 1905, the appropriation of the Bureau had risen to more than $439,000. In that year, the young forestry agency and its energetic leader were given forests to manage; the Forest Service was born.

Up to 1905, jurisdiction over federally owned forests was lodged in the Department of the Interior. Initially, the jurisdiction was derived from legislation dating from the early nineteenth century providing for protection of forests on the public domain from theft. In 1891, however, a landmark law was enacted authorizing the President to set aside portions of the public domain as forest reserves; these lands were not open to entry or settlement, and it was the Interior Department that guarded them. The authority of the Secretary was broadened by an historic statute that became law in 1897 and furnished the foundation for modern forestry practices in the federal government; it authorized him to control and administer the reserves as well as to protect them, and conferred on him the power to make rules governing their occupancy, use, and disposition. These reserves and these powers passed to the Department of Agriculture in 1905.

The transfer, largely the result of skillful efforts by the man who was to become the first Chief—Gifford Pinchot— put an end (over strenuous Interior Department objections) to the anomalous division of functions that existed between 1876 and 1905. On the one hand, the specialized forestry agency in the Department of Agriculture had charge of forestry but not of forests. On the other hand, the Department of the Interior was responsible for the public forests but not for developing forestry. The merger of these functions in one department put an end to this strange duality: the Bureau of Forestry took over the task of protection and management in addition to its programs of research, assistance, and public information; the expanded organization was officially redesignated the Forest Service; and the reserves were legally named “National Forests.”

The area of the national forests was rapidly increased by executive withdrawals of land from the public domain under the act of 1891. Most of these additional reserves were created in the West, where the greater part of the property to which the federal government still held title lay. By 1911, however, attention turned to the East, where whole areas had been completely stripped of trees by loggers, or burned over to make room for farms which were abandoned as better farm land became available farther west and drove marginal farms out of production. It was recognition of the flood control problems resulting in part from these conditions that led to the enactment of the Weeks Act in 1911, which set up the National Forest Reservation Commission and authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to purchase land for addition to the national forest system, provided that such purchases were approved by the Commission and by states in which they were made.

The Forest Service was thus able to move into the East, and the last major legal gap in the powers needed for administration was closed. “1876, 1891, 1897, 1905—these were all red-letter forest years. But 1911, a year of the same hue, deserves somewhat larger type, for it puts the seal of finality upon them all.” 2 The legislative base was complete; no other additional pieces of legislation would or could add such large increments to the jurisdiction of the Forest Service, although important measures did round out its authority in later years.

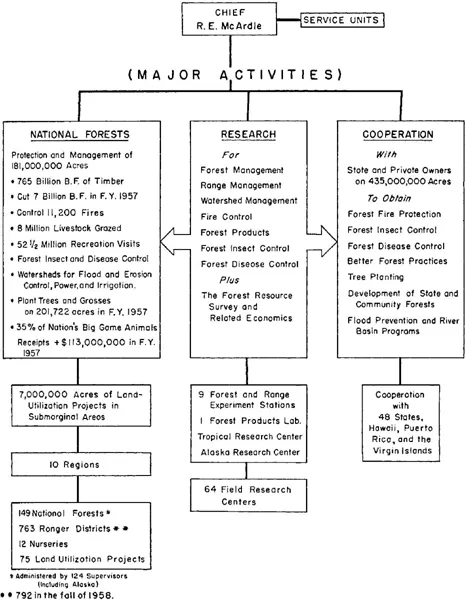

Developing the maximum practical yield and beneficial use of the national forests has from the start been an awesome responsibility. It began in 1905 with 60 million acres concentrated in the West, and the area of forest land under Forest Service jurisdiction has since then been increased to 181 million acres spread over 42 states and a territory. In addition, the Forest Service has been made responsible for administering about 7 million acres of land utilization projects (designed to restore the soil in areas once in submarginal farms which were purchased by the federal government and retired from agriculture during the Great Depression). National forest administration at once became the largest of the Forest Service programs, a position it has never lost.

But the old programs were not displaced; on the contrary, they took on added vigor.3 For it quickly became apparent that the national forests could not solve the nation's forest problems because they encompassed only part of all the commercial forest land in the United States; the vast bulk of the commercial forest land was privately owned, and some was in the hands of state and local governments; so the practice of co-operation with, and assistance to, private owners and states and localities, instituted before the turn of the century, not only had to be continued, but eventually intensified. Likewise, the research programs begun in the nineteenth century became increasingly important; both proper management and effective advising and co-operation demanded more information about the technical and economic aspects of forestry than had ever before been required. So the activities that preceded national forest administration expanded and flourished under the impetus of the newer function. To this day, the program of the Forest Service remains three-pronged.

VOLUME AND VARIETY OF ACTIVITIES4

Carrying out this three-pronged program is, as of 1956, a $128-million operation (not counting an additional $28 million distributed to states, territories, and counties, mainly for roads and schools). At the same time, the Forest Service takes in (during 1956) over $137 million in receipts, from three sources. First and foremost, there are receipts from the sale of forest products (chiefly timber) and from fees for permits for grazing and other uses of the national forests ($118 million in 1956). Second, funds (over $11 million in 1956) are deposited with the Forest Service by private organizations and individuals—by timber operators and other national forest users to pay for improvement of timber stands or ranges, road construction, brush disposal, and other work that the users would otherwise have to do themselves, meeting Forest Service specifications; by community organizations and owners of private lands for a variety of services to communities and landowners not directly connected with the national forests, such as production and distribution of planting stock, technical forestry assistance, and some kinds of research. Third, funds come from other public agencies to reimburse the Forest Service for work it has done for them.

FOREST SERVICE

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

FIGURE 2

The receipts, however, are not freely at the disposal of the Forest Service. Under federal statutes, a portion of them is earmarked for distribution to states, territories, and counties as noted above.5 The deposited funds, under authorizing legislation, are held by the Forest Service to be spent for the purposes for which they were deposited. The rest is returned to the U. S. Treasury, whence, like all other public moneys, it becomes available for expenditure by government agencies only upon appropriation. Thus, the Forest Service, like most other federal bureaus, depends primarily upon appropriations for the bulk of its funds.

Almost three-quarters of the $128 million (roughly, $95 million) spent in 1956 on national forest administration, state and private forestry, and research is applied to the immediate protection and management of the national forests (including road construction and maintenance, and relatively small sums for acquisition of additional land or for adjusting boundaries). Various kinds of co-operation with state and local governments (chiefly, for fire protection, but for other aspects of forestry as well) and with private organizations and individuals (to help them improve their forestry practices, both in economic and silvicultural terms) account for a little under 12 per cent additional. Research makes up about 7 per cent of the total. Thus, almost 94 per cent of all the expenditures goes for these three big programs. The remainder is spent on closely related activities, such as flood control, brush disposal, blister rust control, and pest control, performed to help other agencies (on a reimbursable basis).

Even the smallest of the three main programs (in terms of expenditures)—research—illustrates the widely varied nature of Forest Service work. It comprises forest-management research aimed at improving forest production by basic inquiries into the growth of trees and forests and by testing the application of these findings to the operation of forest properties. Thus, for example, projects have been conducted to determine desirable cutting methods by studies of seed dissemination, to reduce timber losses caused by storms, to improve the quality of timber by experimenting with tree breeding and selection and location, and to convert low-quality hardwood stands to pine. The research program also includes investigations of systems of forest fire control, including statistical reports and studies of fire damage. Another extensive series of projects is designed to discover the interrelationships of soil, plants, and water, and “includes the design and testing of improved cutting, logging, grazing, roadbuilding, and other practices to reduce harmful erosion, flood flows, and debris movements, and to increase the yield and quality of water supplies.” Range research is carried on in order to find ways of converting low-value brush fields to grass, to find appropriate balances between forage for game as well as for livestock, and to better the vegetation for sheep that graze salt-desert shrub ranges.

Important studies of forest economics are conducted by the Forest Service, covering, among other things, timber supply and marketing and industries, such as pulp milling, that depend on forests for their raw materials. Research in forest products has developed new products, lowered costs, and increased the serviceability of existing products, reduced unused residues and found useful outlets for unavoidable residues, and solved other forest products problems; this phase of research encompasses such projects as tests of pulping behavior of different woods, experiments on the strength of wood at low temperatures, accumulation of information on preservation of wood in glued products, and studies of fire hazards in houses. Thus has the original function of the old Forestry Division of the Department of Agriculture burgeoned over the decades. Yet comprehensive and diversified as it is, it constitutes only a fraction of the activities under the jurisdiction of the leaders of the Forest Service today.

Co-operative programs make up a larger portion. For of the more than 664 million acres of forest land in the United States—covering one-third of the total land area of the country—488 million acres now bear, or are capable of bearing, merchantable timber, and of these 488 million acres of commercial forest land, only a little over 17 per cent are in the national forests, Private owners hold more than 73 per cent of it, and state and local governments own almost 6 per cent; federal agencies other than the Forest Service have the remaining 4 per cent. Consequently, it is clear that a bureau committed, as the Forest Service is, to maximizing the use and protection of the nation's forest resources must reach out to influence the management and protective practices of private owners, of states and localities, and, at times, of other federal agencies. Since there are in excess of 4.5 million private owners of commercial forest land, the vast majority of whom possess unde...