A patient comes to see us complaining of distress and suffering. We decide to begin treatment. Over time, the patient brings his associations, we listen, we interpret; there might even be a surprising symptomatic improvement. But sooner or later, we find ourselves at an impasse. The patient repeats his complaints or accounts over and over again. We’ve run out of interpretations that provide symbolic meaning to the patient’s associations, or else these interpretations don’t seem to matter. The patient’s symptoms persist, perhaps even become worse; we are at a loss, we become persecuted, irritated, bored, helpless, numb, or sleepy. We may feel guilty, impotent, ashamed, professionally insecure. We seek supervision. It helps for a while, but the nightmare continues and we can’t wake up from it. This situation can persist for weeks, months, even years. In the best case, we have a hunch, a gut feeling we can’t put to words. We may sense something at the tip of our tongue but find no way of putting our finger on it, and we just let it evade us. We are in despair, dumbfounded. The patient may become openly aggressive, even violent, and threaten to break off therapy; we think it might even be for the best.

This is if all goes well.

Alternatively, the patient brings associations, the analyst makes interpretations, and these lead to a growing array of associations and interpretations. The patient becomes increasingly aware of himself, his history, his family life, his conflicts and inhibitions. The patient may seem to be improving in the sense that he becomes better-adjusted socially and professionally. Of course, there may be periods of despair or anger, but these can be worked through over time. However, this brings to mind Bion’s (1976a) description of a patient who was quite articulate. In fact, articulate enough to make the analyst think that he was analysing him rather well. Indeed, the analysis did go extremely well, but Bion was beginning to think that nothing was happening. Then, after a session, the patient went home, sealed up all the crevices throughout his room, turned on the gas, and died. Bion says he had no way of finding out what went wrong, and yet something undoubtedly had. Analyst and patient were meeting on a non-psychotic level, missing the psychotic part of the personality, present but hardly noticeable.

Bion is always trying to help us become aware of the psychotic part of the personality, lying concealed in each of us to a lesser or greater extent, and which we are so often unable, or unwilling to get in touch with. And yet,

perhaps like a virus hidden in our body that can kill us before we’ve become aware of its existence.

Introduction

Bion is one of the most innovative thinkers in psychoanalysis. Yet, any radical thinker must also be linked to his forebears in an ongoing, everlasting evolution of ideas. Indeed, it might be said that the invariant navel of Bion’s thinking lies in his notion of caesura, a concept denoting both a break and continuity. Bion is no doubt nourished and nestled in the thinking of both Freud and Klein. Notably, he seems to draw on Freud’s Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning (1911) and Klein’s Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms (1946), thereby putting the concepts of thinking on the one hand, and psychotic mechanisms on the other, at the forefront of his thinking. Even though this has facilitated the incorporation of his radical ideas within classical psychoanalysis, it also seems to have created much misunderstanding of his own original contributions, leaving his ideas liable to being appropriated and swallowed up by existing, established theoretical schools of thought. Bion elaborates seemingly familiar terms and concepts but imbues them with fresh, different, and unsaturated meaning. I would therefore like to revisit his thinking about the psychotic part of the personality, highlighting the uncharted realm he seems to explore.

Much like Melanie Klein’s investigations into the minds of young children, delving into the psychotic mind has led Bion to hone the psychoanalytical tools required for the apprehension of psychic reality. It has made possible the exploration of a non-sensuous psychic realm and provided the scaffolding for the analyst’s state of mind in approaching both the psychotic and the non-psychotic parts of the mind. In my view, this has far-reaching clinical implications which I will illustrate with a number of clinical vignettes highlighting various aspects of our capacity to approach this non-sensuous realm as it appears in the psychoanalytic encounter.

Furthermore, I would like to draw attention to the impasses often encountered when we analyse the so-called difficult patient who cannot profit from classical transference and countertransference interpretations or from interpretations deriving from theories of defence, splitting, projective identification, resistance, and so on. Since Bion is referring to phenomena related to Klein’s theories of projective identification, it may seem that he is concerned primarily with psychotic personalities, but as he testifies, this is not so (Bion, 1965). With his distinct understanding of the psychotic part of the personality, Bion is making a qualitative leap in our comprehension of the workings of the human mind.

Bion stressed that the human mind does not operate through predictable relations, such as that of cause and effect, but through non-linear processes of growing complexity1 (Chuster, 2014). He is thus moving from a causal/explanatory attitude, to an attitude that seeks to understand and accept the uncertainty that is inherent in the infinite complexity of human development and personal relations (Meltzer, 1986). This is the move from knowing to intuiting, from a finite two- or three-dimensional space to an infinite, complex, multidimensional space, which the personality, in whom psychotic mechanisms are paramount, often reduces to a one-dimensional point.

Moreover, emotional truth is not static but always transient and in transit. It changes from one moment to the next because the objects involved are ever-changing; one constantly changing personality talks to another constantly changing personality (Bion, 1977a). In the attempt to grasp transient truth, in passage from one moment to another, Bion tries to lean on the method by which mathematics tries to measure a changing situation, a changing shape, a variable movement. “Certain problems”, he writes, “can be handled by mathematics, others by economics, others by religion. It should be possible to transfer a problem, that fails to yield to the discipline to which it appears to belong, to a discipline that can handle it” (1970, p. 91, italics added). Yet, as Meltzer (1978) points out, Bion is now using a mathematizing format more for analogic illustration than as an experimental method. Bion himself stressed that he makes use of mathematics “for evocation of thought and for evocations intended to initiate a train of thoughts” (Bion and Bion, 1981, p. 634).

This qualitative move in the understanding of the human mind is illustrated by Bion mathematically by the move from Euclidean and projective geometries to algebraic geometry and algebraic calculus. Nowadays, he might have talked about complexity theories in mathematics.

Euclidean geometry deals mainly with the mathematics and measurement of static shapes, whereas algebraic calculus deals with the mathematics of change, approximation, and transformation of infinite processes. For example, Euclidean geometry can help us measure the slope of a straight line or the area of a regular shape such as a circle or square. But when we have to find a formula for measuring the slope of a curve, where every point on the curve has a different value, or to calculate the area of an irregular shape, a blob, we need the formulas afforded by calculus, and even that will yield only an approximation.

Emotional life is neither linear nor regular. The patient does not present us with a nicely shaped square or circle, but with an undecipherable blob. Are there any rules to the transformations of the emotional experience? And the complement of this question being – is there a method to the chaos presented by madness? Is there some psychoanalytic counterpart to the algebraic calculus that can be used to comprehend this method? In other words, what is the invariance inherent in the transformation which can help us approach the emotional experience that is irrepresentable, ineffable, and unknowable?

The use of geometric and algebraic conceptualizations, though often deterring to us as psychoanalysts, seems to give the analyst tools for thinking about psychic transformations in disturbances of differing degrees. It facilitates our awareness of what it is that is unknowable in psychic life.

Bion (1977b) refers to Paul Valéry, the 20th-century French poet and philosopher, who said it is assumed that the poet is a person who is undisciplined, disordered, goes into a rhapsodic state, and then emerges, waking up with a poem complete in his mind as the outcome of an undisciplined, intoxicated – literally and metaphorically – state of mind. Yet Valéry adds that he believes that, on the contrary, the poet is much nearer to an algebraic mathematician than to an intoxicated individual. It will thus come as no surprise that Lewis Carroll (originally Charles Dodgson), author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, was in fact also a mathematician who studied abstract and associative algebra. His well-known books are examples of literary nonsense, which has the effect of subverting language conventions or logical reasoning. The effect of nonsense is often caused by an excess of meaning. Appreciating the transience and movement of meaning requires the release of our grip on a two- and three-dimensional reality and surrendering to intuitive perception and imagination, allowing for the apprehension of a multi-dimensional reality.

Bion is trying to describe the intensity, violence, and fortitude of the transformation of the emotional experience generated by psychotic functioning, as opposed to that arising from non-psychotic functioning. He agrees with Klein that the degree of fragmentation and the distance to which the fragments are projected can be seen as a determining factor in the degree of mental disturbance the patient displays in contact with reality (Bion, 1970). Additionally, recognizing the psychoanalyst as an integral part of the psychoanalytic process, Bion has put the emphasis of his work on the analyst’s state of mind and on what is required of him or her in order to move towards an apprehension of the patient’s transformation of the emotional experience. He uses mathematical concepts in attempting to describe the tools necessary for the analyst who would endeavour to tread on psychotic territories of the personality. He goes so far as to say that “mathematics…[is] an important element in the mental processes of the individual which makes it possible for him to be a psycho-analyst” (Bion, 1992, pp. 86–87).

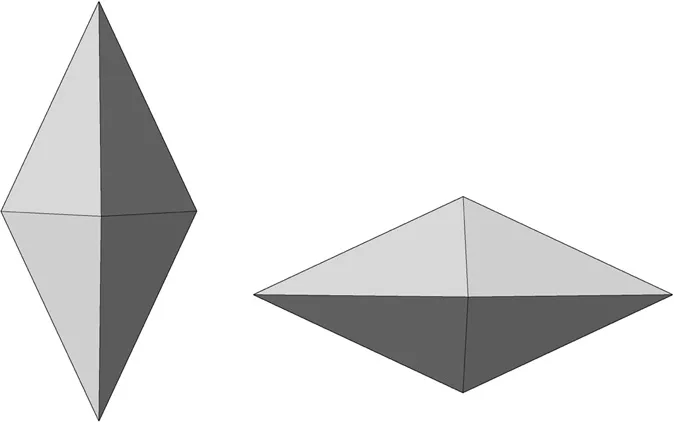

Non-psychotic transformations, which Bion calls rigid motion transformations, require the least effort from the analyst to surmise the original emotional experience. The mathematical counterpart of these relatively simple transformations is analogous to moving a shape in a two-dimensional space, rotating it or mirroring it on a plane. The shape stays relatively the same, and the original shape can be determined if the angle of rotation or the coordinates of the image from the mirror line are given (see Figure 1). For the sake of simplicity, we might say that this amounts to the original definition of transference as described by Freud, where past feelings and ideas are transferred from significant figures in the patient’s life onto the analyst, or vice versa. In order to observe and reveal these relations, the analyst’s insights are informed by the Euclidean geometric dimension of his or her mind.2 However, this yields a rather restricted sense of reality.

Figure 1 Rigid motion transformation

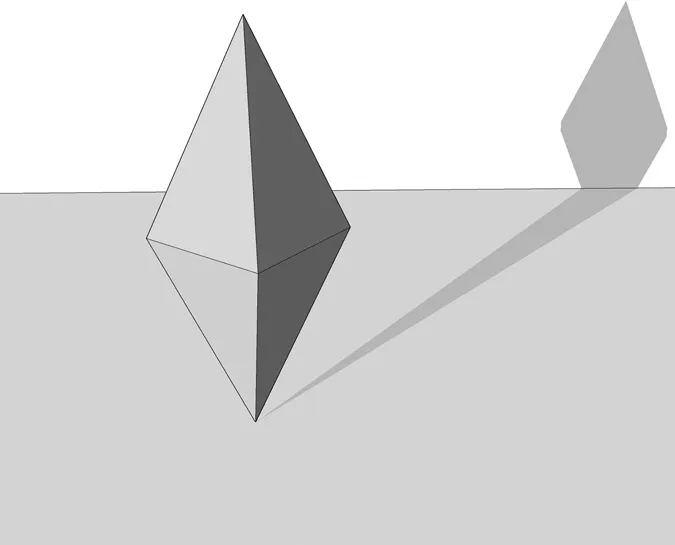

Psychotic functioning, as described by Klein, transforms the emotional experience in a manner that requires a bigger effort by the analyst. These Bion calls projective transformations. The degree of fragmentation and the distance to which the fragments are projected are much greater. The analyst must now be able to comprehend, metaphorically, the essence of projective geometry, whereby the shape of a figure (square, circle, etc.) is transformed by projecting it onto a space from a point of reference. As a result, a square can change its shape to a diamond or trapezoid, a rectangle to a parallelogram, a circle to an ellipse, and so on. The shape will be distorted and will not look much like the original shape, but it does follow a formula. If there is information about the point of reference (distance, angle), the original shape and dimensions of the projected image can be calculated (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Projective transformation

The analyst needs flexibility of mind in order to hear and decipher the unconscious phantasy in its transformed and distorted shape. Moreover, it is not simply transferred onto the person of the analyst but into him, entailing much confusion between patient and analyst. The patient’s transformation of the emotional experience now takes up the whole analytic space so that the transference now occupies the total situation (Klein, 1952; Joseph, 1985). This depiction of the psychotic part of the personality presupposes a three-dimensional space into which parts of the personality are projected. The analyst must be receptive to the patient’s projective identifications, which is the method open to the patient for communicating or evacuating parts of his personality. However, this allows limited contact with parts of the personality that are less structured.

Meltzer (1974) observes that Kleinian analysts “began to notice that interpretations along the lines of projective identification did not seem to carry any weight in certain situations” (p. 342). And when he says “certain situations”, he is referring not to openly psychotic patients, but rather to ones who, on the whole, do not seem terribly ill, people who come because of problems like poor job performance, unsatisfactory social lives, or vague pathological complaints; psychotherapists, people who are somehow on the periphery of the analytic community and want to have an analysis and cannot quite say exactly why.

In clinical work, we too often begin to sense something we cannot put into words. Though it does not necessarily appear in analysis verbally, it is often communicated in a way that makes the analyst feel stirred to the depths by something which seems so insignificant that it is hardly noticeable (Bion, 1977b). Its invariant essence can be grasped only if the analyst releases his attention, suspends rational thinking, eschews his grip on sensuous reality, and surrenders himself to free floating attention, hence “catch[ing] the drift of the patient’s unconscious with his own unconscious” (Freud, 1923a, p. 239).

Thus, by referring to a multi-dimensional mental realm apprehensible through intuition and tolerance of approximations, transience and the notion of infinity, Bion exposes us to what to my mind is his depiction of a psychotic part of the personality.

I would like to approach this mental realm from different theoretical and clinical perspectives in the hope that the movement between these vertices will allow us to get into closer contact with the psychotic part of the personality as depicted by Bion.

Since the predominantly psychotic individual lacks almost any conception of containers into which the projection could take place (either because he has not internalized the containing function or due to his intolerance of the restrictive nature of the container), he is lost in the immensity of mental space. The patient’s emotional experience remains as sense impressions whic...